antiAtlas Journal #5, 2022

Air Deportation and the Settler Colony

Angela Smith

Abstract: Airlines play an important role in border policing and deportation, not only in terms of aviation infrastructure but also as potent, affective national symbols that shape the contours of belonging. In the context of Australia, deportation functions as an assertive act of settler state sovereignty within broader carceral circulations of the Pacific archipelago.

Angela Smith is a doctoral candidate at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, researching aviation and air power in deportation and border policing practices across the Mediterranean. She is interested in political geography, migration, imperial histories and presents, and neoliberal security practices.

Keywords: deportation, airlines, settler colonialism, visuality, detention, Australia, Pacific

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportations"

Directed by William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

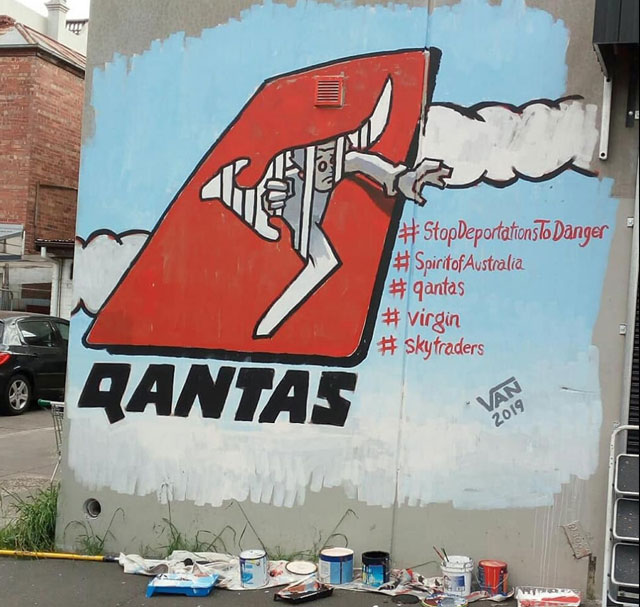

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

Protesting against ‘deportations to danger’ outside the Qantas office. Photo: Zebedee Parkes

To quote this article: Smith, Angela, "Air Deportation and the Settler Colony", published on June 1st, 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL: www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-smith-air-deportation-and-the-settler-colony, last consultation on Date

I. Dispossession and Belonging

1 In recent decades, Australia has increasingly used deportation as a response to rejected asylum seekers and to non-citizens who have breached immigration or criminal law, in line with a global trend towards fusing criminal sanctions with border policing (Grewcock, 2017a; Weber, 2017; Weber and Powell, 2020). Deportation and its relationship to notions of criminality, character and citizenship has been debated in Australia since the early days of the settler colony, founded as a new destination for Britain’s undesirables after the transportation of British convicts to the American colonies ceased. In the centuries that followed the British invasion, the white settler society ensured that race, national identity and citizenship were tightly guarded categories, upheld through consecutive migration policies, including the infamous White Australia Policy. In the 1990s, the notion of the ”bad character” emerged as a device under section 501 of the 1958 Migration Act, enabling deportation of non-citizens with criminal convictions, many of whom had lived in Australia for most of their lives (Grewcock 2017a:123). Deportation effectively transforms legal subjects into “criminal outsiders with no claim to legitimacy within civil society”, rendering established community members as alien (Grewcock, 2017a:124). While this is a function of deportation across many contexts, for Australia as a settler colony in the Asia-Pacific region, forced mobilities are intrinsically linked to questions of belonging, possession, and sovereignty.

Forced mobilities are intrinsically linked to questions of belonging, possession, and sovereignty

As states in Europe and North America, as well as the UK and Australia have governed through exclusion by expelling non-citizens (Kanstroom, 2007), publics have become engaged in contesting deportation across its various sites. Following similar campaigns abroad, public advocacy and debate in Australia in recent years has highlighted the role of airlines in conducting deportations. As a remote island, Australia is entirely dependent on aviation infrastructures in order to carry out removals. Public debates around detention and deportation, the geography of Australia’s border regime, and the role of airlines in forced mobility have foregrounded questions of who belongs in the settler colony. These questions and struggles are reflected in the visual language not only of protests and campaigns, but also in the marketing and branding of airlines.

Issues of belonging and expulsion were debated explicitly during a recent high-profile court case regarding the proposed deportation of two Aboriginal men. The question of whether Aboriginal people can be rendered deportable was taken to the Australian High Court when a Kamilaroi man born in Papua New Guinea and a Gunggari man born in Aotearoa New Zealand faced deportation on character grounds after being convicted of criminal offences. Both men had lived in Australia since they were six years old, and while neither of them held an Australian passport, they each have one Aboriginal parent and both men have Australian permanent residency. One of the men spent 500 days in immigration detention, before being released after the High Court ruled that Aboriginal people cannot be deported from Australia.

In a close 4-3 decision, the High Court ruled in February 2020 that Aboriginal people who meet the tripartite test of biological descent, self-identification, and recognition of Indigeneity by a traditional group cannot be considered aliens, giving them a special status in Australian constitutional law (Karp, 2020a). The case centred around questions of allegiance and sovereignty. The judges put forward a set of propositions laying out a legal logic. One of these propositions stated that according to common law, an alien is a person who does not have a reciprocal relationship of permanent protection and permanent allegiance to the Crown (Love and Thoms vs Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). The Commonwealth argued that while Aboriginal people’s connection to the land is important, it is not equivalent to allegiance to Australia. Lawyers supporting the two men argued that First Nations people have a relationship to the land and waters of Australia which is analogous to the notion of allegiance, which is the basis of citizenship and, therefore, the question of ‘who belongs here, who is a member of us’ is answered (Karp and Davidson, 2019).

The judges further proposed that the common law’s recognition of customary native title “logically entails the recognition of an Aboriginal society’s laws and customs, and in particular, that society’s authority to determine its own membership” (Love and Thoms vs Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). That is, the majority of judges ruled that it is not for the parliament of the day to determine who is constitutionally “alien”, but questions of belonging rest with Aboriginal communities.

next...

2 The government argued that the propositions laid out by the judges would create a class of persons who are outside of both the Citizenship Act and the Migration Act – someone who is neither a citizen, nor an alien. The lawyers for the men, moving beyond this binary conflict, argued there was scope for a new category of belonging: the non-citizen non-alien. The Law Council of Australia, the highest body of lawyers in the country, welcomed the court’s decision, which confirmed that the “question of membership of Aboriginal societies is outside of the legislative power of the Australian parliament” (McGuirk, 2020). While this was considered a landmark case and a major defeat for the deportation powers of the settler state, the fact that this matter went to the High Court reveals something of the logic of possession and displacement inherent in deportation as a practise of settler governance.

Deportation as a practise of settler governance

In a land where sovereignty was never ceded, attempts at deporting First Nations people have a multiplying effect in terms of dispossession and disavowal by the settler state. While the High Court spoke of the ‘metaphysical’ connection between First Nations people and the land, the decision was ultimately made via settler state sovereignty, through invoking the protection of and allegiance to the Crown. The prerogative to determine who belongs and who can be expelled is foundational to the settler state and constitutes an act of possession that is inextricably tied to Indigenous dispossession (Moreton-Robinson, 2015). Deportation and expulsion has a long history in processes of nation-building and remains a way of continuously re-establishing the state (Collyer, 2012:277). In the context of the settler colony attempting to deport First Nations people, there is a triple dispossession at work in attempts to dispossess people of their nation, of their sovereign decision making over who is welcome to enter the territory, and finally in attempts to physically remove people from the continent, as happened in the case of Love and Thoms.

next...

3 Australia’s border regime, including its offshore network of detention sites, must be understood as “foundationally enabled by the ongoing usurpation of Aboriginal sovereignty over their own nations” (Pugliese, 2015:89). A number of First Nations scholars, artists and activists – such as historian Tony Birch, artists Richard Bell and Vernon Ah Kee, and activist and community leader Uncle Ray Jackson - have highlighted the connection between violence at the border and the constant violation of First Nations sovereignty. The authority to decide who to welcome, who to reject and who to expel is a claim to possession, as Amangu Yamatji scholar Crystal McKinnon writes: “Settler sovereignty relies on the violent containment of both Indigenous people and humans seeking refuge in order to actively claim and exercise its own sovereign authority over the colony… However, Indigenous sovereignty endures despite settler colonialism” (McKinnon, 2020:693). Only through the dispossession, desubjectivisation, and zoning (into missions, reserves, welfare institutions etc) of Aboriginal people, could the settler state delineate its territorial sovereignty, name its external others, and work to control them through immigration policies (Pugliese, 2015:90). Aboriginal activists have sought to challenge the mandate of the settler state to extend or deny welcome, through issuing Aboriginal passports to asylum seekers and refugees. Wiradjuri leader and social justice activist Uncle Ray Jackson issued passports to a number of people in 2012, and in 2019, 400 passports authorised by Aboriginal elders were issued and sent to detainees in an off-shore Australian immigration detention centre on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea. Pugliese has suggested that the resignification of the passport as an “Aboriginal technology” both marks Aboriginal people’s unceded sovereignty and their right to offer welcome and hospitality within their own lands (Pugliese, 2015:86).

next...

Aboriginal Passports have been issued to refugees and asylum seekers, including 400 which were sent to Manus Island detainees. Image: ABC.

4 Prominent artist Vernon Ah Kee (of the Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Yidindji, Koko Berrin and Gugu Yimithirr peoples), recognising the patterns of detention, confinement and movement began to produce artwork linking First Nations and asylum seeker experiences. His family were among the thousands of First Nations people who were forcibly removed from the mainland and resettled on Palm Island. Palm Island was also used as a penal institution for First Nations people, and a considerable number of men who had already served their sentences were still removed to Palm Island. This double punishment echoes today in the visa cancellations and deportations of people who have already served sentences for their crimes. A 2018 three-channel video work by Ah Kee shows a couple from Afghanistan seeking asylum in Australia by boat, overlaid with aerial shots of Palm Island. In the exhibition notes, Ah Kee wrote “I cannot escape the idea that Palm Island is the prototype for Nauru, Manus or Christmas Islands” (NSW Museums & Galleries, 2020).

Continuities linking historical and contemporary forms of dispossession and displacement

There are a number of evident continuities linking historical and contemporary forms of dispossession and displacement: the technologies of forced movement and containment; the use of remote territories such as islands; the underlying racial logic of which populations require management and intervention; and whose occupation of the land is to be naturalised as rightful. There are also a number of things that are particular to contemporary air deportations which differ from other forms of dispossession. Contemporary deportations take place at the level of the individual or the family and are justified on the basis of an individual’s particular case – a refugee claim or a criminal history, despite the overwhelming evidence towards racialisied patterns of decision-making. Deportations also rely upon another state – the real or alleged “home” of the deportee – being willing to receive the person (even if the receiving state is coerced or compelled by financial incentives). Deportation is thus both the act of expelling someone and the relocation of that person elsewhere (Walters, 2016:441). This “elsewhere” is fundamental in legitimising the expulsion of deportees, regardless of the relationship between the individual and the place they are expelled to, which may be one of estrangement or danger. Chelsea Watego argues that while the colonial imaginary may insist that Aboriginal people exist in a “land far, far away, in a faraway time”, a place she describes as a “dispossessing location”, she reminds us that Indigenous sovereignty is asserted in every claim of “still here”and in every avowal of “sovereignty never ceded” (Watego, 2021:49).

next...

II. Archipelago of Detention and Forced Mobility

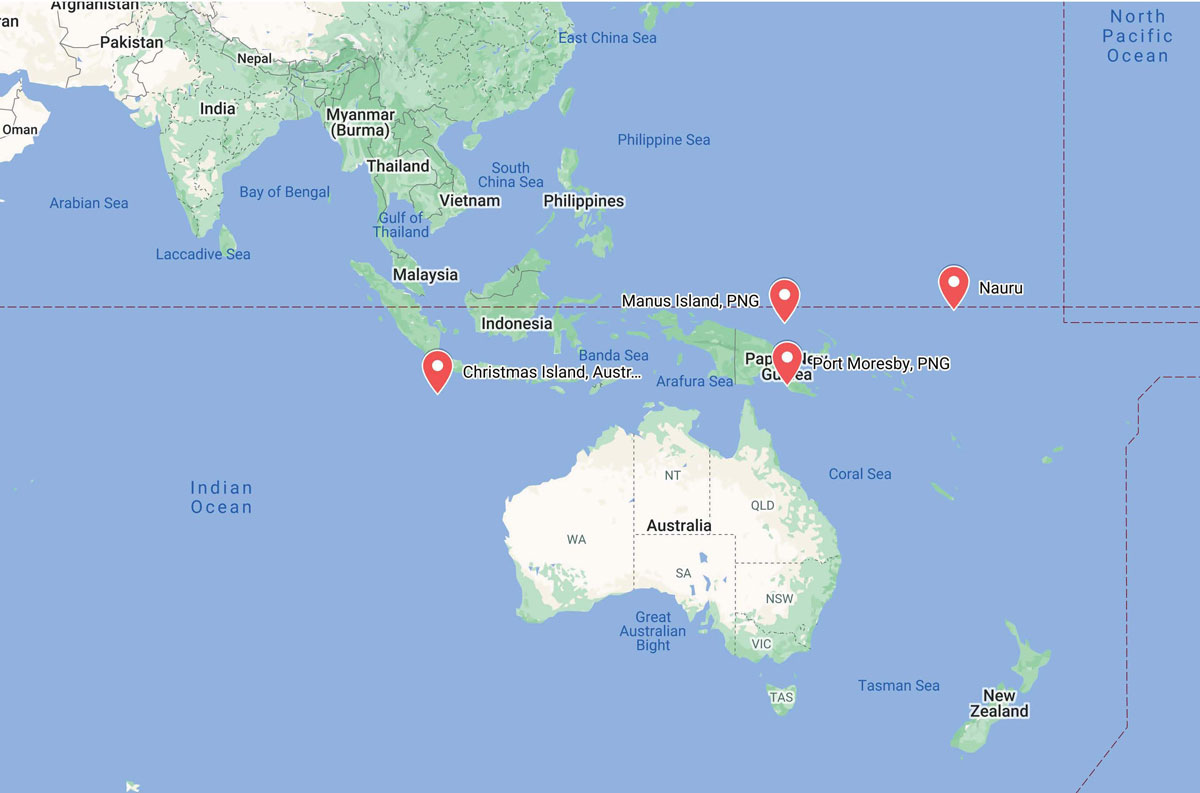

5 While the case determining whether two Aboriginal men can be deported is particularly stark, struggles over containment, forced relocation, and Indigeneity echoes through a wider geography in the Australasia-Pacific region. Air deportation and removals from Australia are intrinsically linked to forced mobility across an archipelago of islands in the region including Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as offshore detention and processing sites on the Australian territory of Christmas Island, on Nauru, and in Port Moresby and on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. Asylum seekers and prospective deportees within Australia’s detention network are moved between various offshore and onshore “facilities” including detention centres, transit accommodation, residential housing, and alternative places of detention (APODs) such as hotels. Hotels have been used as seemingly benign APODs by the Australian government since at least 2010 and have been described as a site of “civil penality” for their appropriation of civil sites and practices into the state’s punitive carceral apparatus (Pugliese, 2009:155). Hotels as detention sites garnered widespread public attention in 2019-20 when in the context of COVID, detainees staged protests from their hotel cells (Burridge, 2020; Loughnan, 2020). Forced or coerced mobilities between these various detention sites have a punitive effect, serving to “isolate, punish and disorient” detainees (Gill 2013), but also to sever their networks of support, denying them stability, and ultimately encouraging them to give up on their refugee claims and “voluntarily” return (Peterie, 2021).

Forced mobility across an archipelago of islands in the region

Asylum seekers in indefinite detention experience multiple forced movements between these sites and describe the distress and grief of being forcibly relocated within a prison system as “its own act of torture”. Circulations within and from the immigration detention system are substantial, with more than 8,000 involuntary aerial movements of people, including transfers and deportations, taking place between July 2017 and May 2019. The carceral power of the state therefore includes “punitive mobility” as well as confinement (Mountz, 2013). Forced mobility has a long history including convict transportation, slavery and forced labour, the expulsion of people for the purposes of land appropriation and colonisation, and more recently, systems of rendition and extradition (Walters, 2018:2801). This multitude of aerial movements at the behest of the state draws attention to the state’s own mobility – the ways in which its actors, infrastructures and resources are mobilised in the governance of migration. Deportation is thus located within a network of circulation and control, that also includes both movement between and containment within detention sites.

next...

6 Kurdish writer Behrouz Boochani, who was detained by Australia on Manus Island for six years, has argued for these facilities to be named for what they are: prisons (Boochani, 2019). In his “Manus Prison Theory”, a philosophical and creative project developed with collaborator Omid Tofighian, Behrouz centres the knowledge and insights of detained asylum seekers to analyse Manus Prison not only as a site, but as an ideology and set of institutional cultures (Tofighian, 2020:1144). Central to Manus Prison Theory is the notion of the “kyriarchal system” – a series of “intersecting and mutually reinforcing structures bent on domination, repression and submission” (Tofighian, 2020:1142). For Behrouz, Australian border violence is linked to Australia’s colonial imaginary. Behrouz sees the two islands – Manus and Australia – as deeply implicated in one another: Australia was a penal colony and is using Manus as an island detention centre, Australia colonised Papua New Guinea, and Papua New Guinea colonised Manus Island (Paik, 2021). Manus Prison Theory sees offshore detention not as something peripheral or remote, but as a product of modern colonial histories and ideological networks that exists at the heart of the nation (Tofighian, 2020:1148). Circulations and containment of detainees within Pacific detention networks therefore draw on not just physical infrastructures, but also architectures of knowledge, imagination, and governance.

next...

Sites that have been used for Australia’s offshore detention and processing over the last two decades. Image: Created in Google Maps

III. COVID and Christmas Island

7 During the COVID pandemic, deportations from Australia stalled, as the nation closed its international borders early in the pandemic (in March 2020). Prior to COVID, government figures from February 2020 suggested that there were almost 50,000 people whose asylum claims had been rejected and were awaiting deportation (Stayner, 2020). These asylum seekers had all arrived by plane. In addition, the government has been increasingly cancelling visas on character grounds, usually due to a criminal conviction. Changes to Section 501 of Australia’s Migration Act in late 2014 lowered the threshold for criminal deportation and removed the prohibition on the deportation of long-term residents.

These changes have significantly extended the capacity of the Australian government to remove people

Ministerial powers were broadened to allow the Minister to cancel existing visas on character grounds and introduced mandatory visa cancellation in cases where the visa holder had been sentenced to a prison term of 12 months or more. Since these changes in 2014, the number of visa cancellations on character grounds increased by over 1,240% by the end of 2020 (Department of Home Affairs, 2021). Politicians celebrated the new regime as a crime prevention measure (Billings, 2019). These changes have significantly extended the capacity of the Australian government to remove people who have lived in Australia for many years, and who have extensive social and community ties (Grewcock, 2017b). Decisions regarding visa cancellations do not take into account personal circumstances, the seriousness of the offences committed, nor the length of residence in Australia (Weber and Powell, 2020). Around 6,300 people have had their visa cancelled on character grounds since the changes were introduced (McGowan, 2021). The most common reason for visa cancellations on character grounds are due to drug offences (McHardy, 2021b).

next...

8 For people who have served a prison sentence and had their visa cancelled, the Australian government operates a “Prison to Plane” removal system, which is referred to as P2P (Department of Home Affairs, 2018). It is clear in the government’s conceptualisation that there is a direct corridor which can swiftly transfer deportees from one carceral site to another: from the prison to the plane. There are two types of P2P removals: either a person is removed directly from prison to an aircraft without being physically detained in an immigration detention facility; or, the person is released from prison and there is a delay in their departure, in which time they are held in an immigration detention facility for up to 72 hours until they can be put on a plane.

One carceral site to another: from the prison to the plane.

With the closure of Australia’s international borders in March 2020, onshore immigration detention facilities became crowded with people whose visas had been cancelled. The government took the opportunity to reopen the Christmas Island North West Point facility in August 2020 to house people who had their visas cancelled on character grounds, pending deportation. The corridor from prison to the deportation plane was blocked, so the government instead put detainees on planes to remote Christmas Island. From August 2020 through to May 2021, around 250 potential deportees were transferred to the facility. The deportation corridor thus stretches more than 1,500 kilometres from mainland Australia to a remote territory, while still being within Australia’s jurisdiction. The government has defended the reopening of the facility at a cost of AUD$55.6 million.

next...

The Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre at North West Point, Christmas Island. Photo: DIAC images.

IV. “On Character Grounds”

9 Visa cancellation on character grounds has a punitive rationale, which deems people outside of the social contract, owing to their offending and non-citizen status, with incarceration and deportation used to reinforce the boundaries of membership of the Australian polity (Weber and Powell, 2020:247). The changes to the Migration Act have disproportionately affected New Zealanders, many of whom are permanent and long-term residents of Australia, constituting the largest nationality group to have their visas cancelled under S501. Between January 2015 and March 2020, over 2,000 New Zealanders were deported from Australia, with the majority (60%) being Māori or Pasifika peoples. Those deported to Aotearoa New Zealand are thus not only a racialised and criminalised group, but also a group of predominantly First Nations people, being deported within the Pacific carceral archipelago. The Australian government has shown little mercy in terms of who is vulnerable to expulsion: New Zealanders deported include a 70-year-old woman who had lived in Australia for 55 years (Dunn, 2021), a quadriplegic man who had been in Australia 36 years (Milman, 2015), and a 15-year-old child who was deported alone (McGowan, 2021).

Australia’s legal and migration regime imposes a triple punishment for non-citizens

If Australia’s legal and migration regime imposes a triple punishment for non-citizens in the form of imprisonment, immigration detention and then deportation, deportees face a further multiplier in Aotearoa New Zealand in the form of ongoing monitoring and supervision. In November 2015, just days before a plane of deportees was due to land, parliament rushed through legislation establishing a new monitoring regime for the so-called ‘returning offenders’ (McHardy, 2021b:2). Special conditions are routinely applied to this group (such as electronic monitoring and curfews) subjecting them to a greater level of restriction and ongoing monitoring, and a weaker standard of legal protection, than people released from Aotearoa New Zealand prisons (McHardy, 2021a). In doing so, the state has adopted the same logic of risk profiling and pre-emptive management that the Australian state has deployed; ‘”importing” the risk logics of the Australian border regime into its own securitisation project’ (McHardy, 2021a).

next...

10 Scholars have cautioned against understandings of deportation as an “event”, but rather to consider deportation as a process that spans spatially and temporally from the condition of deportability through to the days-months-years of estrangement and marginalisation after the deportation has taken place. In New Zealand’s 2015 Returning Offenders (Management and Information) Act (ROMI), we see the formalisation and legal encoding of protracted punishment of deportees. The ROMI Act sets conditions on where a returnee can live, work, and even who they can or cannot associate with (McNeill, 2021). This securitising logic continued to echo across the Pacific, with Samoa proposing a similar measure in the proposed 2019 Samoan Returning Offenders Bill (Ah Tong, 2019). Under the proposed Samoan Bill, all ‘returning offenders’ would be required to report to a parole officer, require permission to change accommodation, and be subjected to similar restrictions around who they were allowed to live, work, and socialise with. While in Australia offenders are subject to differential treatment on the basis of being “foreign”, upon being deported to another Pacific country, people are again differentially treated on the basis of their outsider status, and the “foreignness” of their offending. In the high profile, tense conversations about deportations from Australia, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has said: ‘Send back Kiwis, genuine Kiwis – do not deport your people, and your problems’ (Moir, 2020), pointing to both the Australianness of these deportees, and raising the question of what constitutes a ‘genuine’ New Zealander.

There is a deeply affective and relational element to this punishment

The restrictions legally inscribed through these Returning Offenders bills, only serve to compound the challenges that returnees already face in trying to build a life in a country where they may have very little social or economic resources, are in need of employment, accommodation and healthcare, and may not speak the language or be familiar with the social systems and structures. While the Australian criminal justice and deportation system is responsible for the racial disparity of those deported to Aotearoa New Zealand, the New Zealand state continues to treat this group as a risk to be contained (McHardy, 2021a). The deportations are carried out with no consideration of family separation, with New Zealanders leaving behind children in Australia that they will not be able to visit again. There is a deeply affective and relational element to this punishment, which has also been used against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

next...

11 The deportation powers of the Minister and Home Affairs department may be further expanded with a new amendment to the act – the Migration Amendment (Strengthening the Character Test) Bill 2021. A key change made by this bill, if it passes, is that the sentencing threshold for a designated offence is based on the maximum penalty available, rather than the actual sentence given. If a relevant offence has a maximum penalty of at least two years imprisonment, any person convicted of the offence will automatically fail the character test, regardless of their actual sentence. That is, while a judge may be able to hear evidence and consider the overall context of the offence and the situation of the offender in order to determine a sentence, all of this will be disregarded. By disregarding these contextual and case-specific evaluations, the Government is seeking to combat the discretion of judges who, taking the risk of deportation into account, were sentencing some people below the threshold to avoid visa cancellations (Commonwealth of Australia, 2017). This Bill would further expand the power of the Minister to override legal outcomes and base visa cancellation decisions on something entirely speculative and fictional – a sentence that could have been given, but was not.

next...

V. Cruelty and spectacle

Mobile billboards made their way around round capital cities in 2018 targeting Qantas’ role in deportations.

12 Prior to the arrival of detainees with cancelled visas on Christmas Island, the only people detained on the island at that time were a Tamil family of four taken from the Queensland town of Biloela, on Gangulu country. The asylum seekers were removed from the regional town after their asylum claims were rejected and were first detained in Melbourne before being sent to Christmas Island in August 2019, after a dramatic mid-air injunction via telephone prevented them from being deported back to Sri Lanka and their plane was forced to land in Darwin. Home Affairs confirmed the cost of detaining the family on Christmas Island for the first fourteen months was AUD$3.9 million. Combined with the bill for detaining them in Melbourne and legal costs incurred by the federal government, as of 2021 the government had spent over AUD$6 million dollars detaining a family of two adults and two Australian-born small children (Taylor, 2021). In an era of supposed neoliberal efficiency and market rationalisations, what can be made of such excessive, arbitrary, and grossly wasteful expenditure other than the mobilisation of cruelty and spectacle? At a time when Australia has abandoned economic support for temporary migrants during COVID (Berg and Farbenblum, 2020), what other ends might this carceral expenditure have been allocated towards? The full penal force of the state has been exercised against this family, who have the strong support of their regional Queensland community. The latter has waged a noisy campaign to convince the government and the wider public of the family’s belonging in the community. While a somewhat exceptional case, in terms of the level of public economic and affective investment, the detention and proposed deportation of the Biloela family has put deportation and airlines’ complicity firmly back in the arena of public debate.

next...

The campaign featured the faces of baby Tharunicaa and her sister Kopika from Biloela, who at the time, were the only two children left in Australian immigration detention (Sanchayan and Truu 2021)

13 While Qantas is not the only airline involved in forced movements within Australia’s detention and deportation regime, it has been at the centre of public pressure and campaigns for its role. In the highly visible campaigns to save the Biloela family from deportation, Qantas received public petitions with thousands of signatures, statements signed by diverse and prominent individuals, and were met with protests outside their offices. The kangaroo icon synonymous with the Qantas brand has served as a synecdoche for the airline in anti-deportation campaigns. Against the backdrop of successful anti-deportation campaigns in the UK, USA and Europe targeting airlines, and a growing movement in Australia, the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) applied pressure to Australian airlines to review or abandon their contracts with the Department of Home Affairs. In 2018 and 2019, the ACRR put resolutions to Qantas shareholders at the company’s Annual General Meeting calling on Qantas to withdraw from, or at least review, its role in undertaking deportations. While the proposal was met with greater support among shareholders in 2019 than the previous year, the airline remains committed to its role in deportations, stating that it is not for airlines to adjudicate on complex immigration decisions. While in this response the company seeks to elude social responsibility through deferring to the government and retreating into its merely corporate position, the airline has played a prominent role in both social justice issues and in the public imaginary.

next...

Protesting against ‘deportations to danger’ outside the Qantas office. Photo: Zebedee Parkes

A mural by artist Van T Rudd in support of the Stop Deportations to Danger campaign, Melbourne. Photo: Van T Rudd

VI. ‘Spirit of Australia’: airlines and publics

14 Qantas is one of Australia’s most recognisable brands. It’s the country’s national carrier and the world’s oldest continually operating airline. Commercial aviation in Australia began in the 1920s with the founding of Qantas in the Queensland “outback”. The two founders of the airline were returned soldiers who had met while serving with the Australian Flying Corps in Palestine during WW1, highlighting once more the circulations of empire, militarism, and aviation. Indeed, the founding chairman of Qantas wrote that the airline was ‘inspired by the spirit of ANZAC’ – the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. Despite its small population, Australia was highly active in the developing field of aviation. Aviation was quickly recognised as essential to the ongoing project of colonisation across the continent with aircraft enabling the conduct of aerial land surveys to enclose and appropriate land for settlers, allowing for the connection between sites at the end of unfinished vast rail networks, and providing much quicker exchanges between states and with Britain through the introduction of air mail. Air power also provided medical services for those settlers at the internal frontiers, expanding the colony inwards on remote cattle stations and missions through the founding of the Royal Flying Doctor Service in 1928. Qantas flights during the 1920s also carried fresh butter, ice, and fresh fish to those in the interior of the country. The development of aviation was also crucial to Australia’s assertion of power in the Pacific, particularly during World War II. Aviation was uniquely important in Australia given the distant geographies across the island continent, and the sense among settlers that Australia was an outpost of empire that needed to remain connected to Britain and the rest of the Anglo world.

Aviation was uniquely important in Australia given the distant geographies

As the settler colony continued to build a “native” subjectivity, this was reflected in the corporate branding of Qantas. The kangaroo logo was launched in 1944, based on the design of the Australian one penny coin. When Qantas partnered with Britain’s Imperial Airways in 1935 to fly between Australia and the United Kingdom, the route was named the “Kangaroo Route” and was achieved in 31 “hops”, connecting the metropole and the colony by air. With its iconic red and white stylised kangaroo logo gracing the tails of its aircraft, Qantas seeks to assume an autochthonous position. The kangaroo, an animal native to the island continent, also features on the country’s coat of arms to symbolise forward propulsion and advancement; the rudder-tailed marsupial apparently cannot move backwards easily.

next...

The Commonwealth of Australia Coat of Arms features the kangaroo and the emu, two native animals which cannot move backwards easily.

The iconic kangaroo logo has been modified over the years to become increasingly stylised. Here a popular design sits on the tarmac at Sydney airport. Image: Edwin Leong.

15 For the past two decades, Qantas’ marketing has centred around the widely recognised advertising campaign “Spirit of Australia”, which is perhaps one of Australia’s most successful campaigns. The airline has produced at least five iterations of a video featuring Peter Allen’s 1980 song “I still call Australia home”. Four of the videos, produced in 1998, 2000, 2004, and 2009, have all featured choirs of children singing the song in panoramic global and national landscapes. It has been noted that the timing of the release of each advertisement coincided with national events such as the Sydney Olympic Games (Drew, 2011). The four videos tap into nationalistic mythologies about landscape, heritage, freedom, exploration, and the outback (Drew, 2011). The advertisements construct a particular relationship to adventure, travel, home and belonging. It points to currents of movement and exploration that are both familiar in the contemporary context, and at the heart of Australian colonial history (Moreton-Robinson, 2015:4).

This decades-long iconic campaign reaffirms a national subjectivity

The protagonist of the song is an Australian traveller who, despite being far away and seeing all the world has to offer, realises that his emotional allegiance is with Australia and he will always come home (Drew, 2011:324). Visually, the children represent this adventurer as they move around recognisable global sites. A line of the song celebrates this mobility: “I’m always travelling, I love being free”. Qantas demonstrates that it provides the aviation service to both take the Australian traveller to these global destinations, and then, recognising the traveller’s nostalgic longing, it’s ultimately the brand that will deliver the affective homecoming. The children featured with key singing roles in the earlier versions of the video all appear to be white, while Aboriginal children feature variously as located within the landscape, or as an exotic culture to be encountered by the (white) travelling children. In the 2009 version, the opening verse is sung in Kala Lagaw Aw language by a Torres Strait Islander child who is part of the choir, and the sentimental homecoming for the children is to Australia’s red desert centre (Drew, 2011). The 2020 home video campaign consciously represents Australia’s diversity in a way that the earlier videos did not. Ultimately, this decades-long iconic campaign reaffirms a national subjectivity that is youthful, mobile, white, and free, with deep affective ties to Australia’s vast landscape.

next...

I Still Call Australia Home, Quantas TV commercial (1999). This version of the advertisement continues to amass new likes and comments in 2021 under ongoing COVID border closures, with many commentators expressing their own nostalgia and longing to return “home” to Australia.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbGuqmaDgLA

I Still Call Australia Home, Qantas TV Commercial, 2009

Source : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbGuqmaDgLA

16 The fifth iteration, the 2020 revival of the video, sought to mobilise solidarity around COVID lockdowns, with the children recorded on mobile phones singing from their homes. Qantas, seeking to recuperate some of the billions that it has lost during the pandemic, offered loyal passengers the chance to take a “joy flight” in October 2020. The “Great Southern Land” flight was a seven-hour return journey departing from Sydney and looping around popular landmarks like Uluru, Kata Juta and the Great Barrier Reef to offer altitude-deprived passengers spectacular views. The advertisement for the flight claimed “From the sky, there are no border restrictions” (Cockburn, 2020). Economy tickets were priced at $787 and business class at $3,787, and the flight was completely sold out in less than ten minutes. The joy flight, condemned by climate campaigners in a year that saw vast swathes of the Great Southern Land destroyed by bushfires, clearly tapped into a public longing. The flight was sold as a chance for nostalgic reminiscing of days gone by – even if those days were not so long ago – where passengers could experience all the rituals and sublime birds-eye views associated with air travel. While the flight offered some people the chance to soar above border restrictions, for others, the border is enforced through the mechanisms of air travel.

From the sky, there are no border restrictions

While Qantas’ marketing and branding has occupied a prominent public position, the other dimension to Qantas’ presence in civic life is through its progressive corporate positioning on social issues. The airline and its leadership have repeatedly affirmed a commitment to LGBTIQ+ rights, women’s rights, and Indigenous rights. The airline was highly active in its support for the legalisation of same-sex marriage during a controversial national debate and public plebiscite on the issue. Qantas CEO Alan Joyce was outspoken in his support for marriage equality throughout 2017, which was legalised in December that year. Qantas is also a sponsor of the annual Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, and in 2017 unveiled a new rainbow livery, using the body of an aircraft to paint its progressive values.

next...

QANTAS launched its “rainbow roo” livery to celebrate its partnership with Sydney Mardi Gras.

Activists leafleting outside the Qantas stall at the 2019 Mardi Gras

17 Corporate sponsorship of the Sydney Mardi Gras however is contested, and there is significant mobilisation by those who want to restore the protest roots of the festival and reject the event’s collaboration with corporations and police, and who view combating racism and border policing as part of queer politics. Qantas has been targeted by activist groups like “Pride in Protest” for its role in deportations and the group has used the Mardi Gras as an opportunity to campaign against Qantas’ role in forced removals. Similarly, Qantas-sponsored “Women of Influence” award nominees have used their platform to call on Qantas to stop participating in involuntary transportations, calling Qantas “hypocritical” for celebrating nominees’ work while deporting asylum seekers. Qantas has also used the material body of the plane as a canvas for displaying First Nations’ artwork. Since 1994, through its “Flying Art” series, the airline has commissioned five liveries based on artworks by First Nations artists.

The airline manages to perfectly represent and activate liberal nationalisms

Qantas has attempted to distance itself from the types of criminal law and migration governance decisions that have a devastating impact on people’s lives in the form of visa cancellations and deportations. It has tried to retreat into its utilitarian transportation role as just an airline. However, apart from its obvious complicity in forced relocations as a transport provider, the company has also actively positioned itself in a highly affective bond with Australian publics since its foundation. Qantas reflects to the Australian public a particular image of what it means to belong to this land. The airline manages to perfectly represent and activate liberal nationalisms, holding progressive values around certain social justice issues and mobilising a highly nationalistic settler imaginary around movement, place and belonging.

next...

The planes “Nalanji Dreaming” and “Wunala Dreaming” were designed by Aboriginal-owned design agency Balarinji. Photo: Qantas newsroom.

VII. Airlines and capital

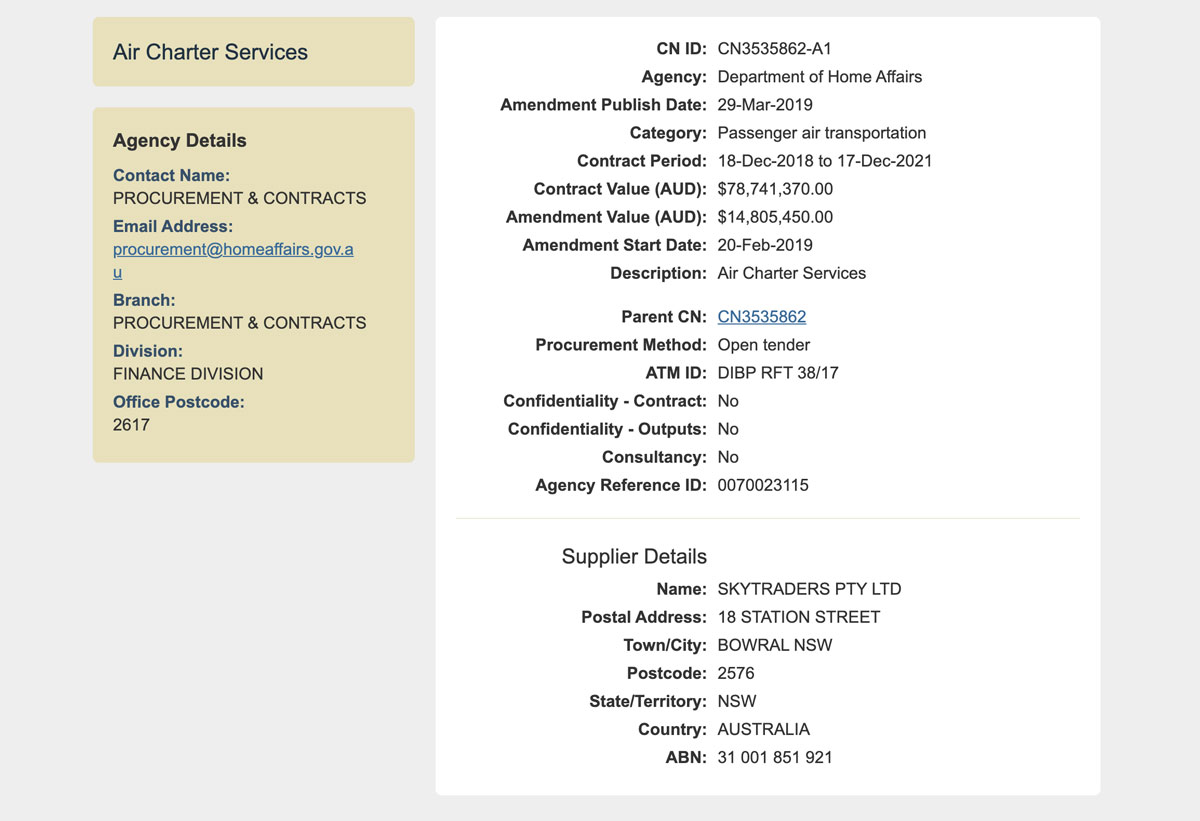

18 While Qantas occupies a prominent affective place in the public imaginary and is particularly the target of anti-deportation campaigns, figures released by the Department for Home Affairs showed that the bulk of departmental transfers are conducted by charter flights. In the 2018-2019 financial year, the department spent $400,000 on commercial flights with airlines like Qantas, and a staggering AUD$5.7 million on charter flights (Karp 2020b). When the Tamil family of four asylum seekers faced a deportation attempt, supporters of the family began scanning for flights to Colombo, thinking they might be on a Qantas jet. They found instead that the family was being taken by a private plane belonging to Skytraders, a charter company that has earned significant profit through its contracts with the Department of Home Affairs. Skytraders, who have been contracted by the department since 2010, signed a contract for the period 2018-2021 totalling almost AUD$79 million for “passenger air transportation”.

The government thus promoted its own border regime cruelty

The Australian government’s border operations, and particularly its offshore detention regime, are notoriously shrouded in secrecy. Access to information, or indeed to people, is made incredibly difficult for researchers, journalists, and the general public. In this spirit, Skytraders sought to keep their flights to Nauru and Christmas Island out of the public eye by requesting the Flightaware tracking system to hide its charter flights to these destinations, from as early as 2012 Public awareness of the company grew however, in 2014, when the government depicted a Skytraders branded aircraft in a graphic novel produced and distributed to deter Afghan asylum seekers. The orange and white Skytraders plane was shown in the graphic novel transferring asylum seekers to a remote island. The graphic novel attempted to faithfully represent the horrors of the Australian border regime, including boat interceptions, forced plane transfers, detention on remote islands, and the medical problems, depression and sense of despair that a detainee may experience. The government thus promoted its own border regime cruelty as a deterrent.

next...

The Australian Government’s Tenders website shows the Skytraders contract for 2018-2021, which was amended in 2019 to add an additional $14,805,450. Image: Screenshot of https://www.tenders.gov.au/Cn/Show/c8efbc0f-00f5-997f-fbef-a2488c4e1271

A 2014 graphic novel produced by the Australian government

The Skytraders website describes the services it provides to the Department of Home Affairs as “discrete” and offering “operational certainty”. Image: Screenshot from https://skytraders.com.au/special-missions/

19 The services provided to the Department of Home Affairs are described as “special missions” on the Skytraders website; special missions which respond to “political imperatives” with discretion. The company also promises the greatest operational certainty with the “smallest footprint”. While this may be referring to sustainability measures, it also conjures an image of stealthily tiptoeing to avoid detection, or to avoid dealing with a controversial subject.

The projection of the nation into the sky

Other key aspects of Skytraders’ work include providing air services to the Australian Antarctic Division, linking Hobart and Antarctica, and were in fact the first civilian airliner to undertake flights to Antarctica. They also specialise in surveillance and survey projects, working with the Victoria Police Air Wing, surveilling Australia’s Economic Exclusion Zone, and working with oil and gas companies like Chevron. Skytraders also trains Australian Defence Special Forces, specifically in parachuting. On the “defence” section of the Skytraders website, they promote a video of the Australian Defence Forces “Red Berets” parachuting out of a plane, flying the Australian flag and emitting plumes of decorative red smoke as they drop into a Sydney sports stadium to deliver the match ball for a rugby league game held on ANZAC Day – the national remembrance day commemorating those who died at war. This performance – assisted and promoted by Skytraders – is reminiscent of the “aerial theatre” of the early twentieth century which was wildly popular in Britain and Australia. Aerial theatre, as a popular form of entertainment, used aviation spectacles to promote militarism, nationalism, modernity, and technological force; what Peter Adey has called “the performance of a political community and the projection of the nation into the sky” (Adey, 2010:67 in Holman, 2019).

next...

Skytraders-trained ADF members parachute into a commemorative rugby game to deliver the game ball in Sydney. Image: Screenshot taken at https://skytraders.com.au/defence/

20 This performance of political community and projection of the nation into the sky is not only the reserve of aerial theatrics such as parachutists emitting plumes of red smoke, but is present in the way that publics relate to aviation, whether in advertisements for Qantas or in public struggles over air deportations. There is a strong sense of nationalism instilled in the national carrier, and persistent sentimental attachments to the embodied experience of flying – even in the face of the devastating impacts of climate change - as evidenced by the rapid sellout of tickets for Qantas’ “flights to nowhere” during the pandemic, which included 13-hour round trips over the melting ice of Antarctica (Escape, 2020). National carriers like Qantas are thus engaged in producing a range of affinities, and reflecting back to publics a modern, mobile, liberal nation. With links to military histories and presents, and motivated by neoliberal profit imperatives, Qantas and Skytraders play a key role in defining and policing the Australian political territory. While this takes place in part via the promotions and performances they produce in the visual and discursive realms, another more operational aspect entails being on the front line of determining who can fly and who can not, and operationally carrying out forced mobilities, relocations and removals at the behest of the state. The role of airlines in upholding Australia and its borders is thus not limited to their role as simply a vehicle or efficient form of transport. For their role in propelling deportations and forced relocations throughout Australia’s detention and deportation network across the Pacific archipelago, Australia’s airlines have rightfully come into the public spotlight.

next...

21 Airlines and aviation infrastructure provide the Australian state with the material capacity it needs to carry out deportation. In his work on the history of the deportation train in the United States, Ethan Blue has argued that the deportation train “put steel” into federal immigration laws that allowed the deportation state to cohere (Blue, 2015:176). In the US context, he argues, the “material apparatus of removal posed a vital step in the production of alienage, and therefore of citizenship” (Blue, 2015:176). In the context of settler colonial governance, questions of citizenship and alienage can not be resolved while the colony persists, and Indigenous activists, artists and scholars have sought to resist Australian colonial sovereignty through extending forms of welcome to asylum seekers, and providing critical art and scholarship on links between the border regime, the settler state, and the displacement and incarceration of First Nations peoples. Building upon these linkages, this article has discussed the continuities of spatial and carceral technologies, geographical fictions, and racial logics which persist across different forms of dispossession within and from Australia, where the state has variously sought to ‘spatially and legally dismantle’ claims to belonging (Blue, 2015:176). In thinking through aviation as an infrastructure of militarism and profit, as well as a site of liberal civic-mindedness and nationalisms, the “deportation plane” is revealed within a broader field of power (Walters, 2020). Looking at the deportation plane also reveals something of the vast distances and reach of the deportation state. Through tracing the connections and circulations that constitute air deportation from the settler colony, distant geographies from Manus Island to Palestine to Antarctica become connected, and diverse subjects from Samoa to Kurdistan to Palm Island become bound together in a logic of onshore and offshore violence, containment, and forced mobility.

next...

References

22

Ah Tong Lanuola Tusani Tupufia, 2019, “Bill to Give Police Monitoring Powers of Returnees”, Samoa Observer. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.samoaobserver.ws/category/samoa/39138

Arvin Mardin, 2021, “Let Me Tell You How They Move Us”, Overland Literary Journal. Accessed 11 May 2021. URL: https://overland.org.au/2021/04/this-is-how-they-move-us/

Berg Laurie and Farbenblum Bassina, 2020, As If We Weren’t Humans: The Abandonment of Temporary Migrants in Australia during COVID-19. SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 3709527. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

Billings Peter, 2019, “Regulating Crimmigrants through the ‘Character Test’: Exploring the Consequences of Mandatory Visa Cancellation for the Fundamental Rights of Non-Citizens in Australia”, Crime, Law and Social Change 71(1): 1–23.

Blue Ethan, 2015, “Strange Passages: Carceral Mobility and the Liminal in the Catastrophic History of American Deportation”, National Identities 17(2): 175–94.

Boochani Behrouz, 2019, No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, Picador Australia.

Burridge Andrew, 2020, “Hotels Are No ‘Luxury’ Place to Detain People Seeking Asylum in Australia”, The Conversation. Accessed 25 November 2021. URL: http://theconversation.com/hotels-are-no-luxury-place-to-detain-people-seeking-asylum-in-australia-134544

Cockburn Paige, 2020, “Qantas Flight to Nowhere Sells out in 10 Minutes”, ABC News, September 17 2020. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-18/qantas-flight-to-nowhere-sells-out-in-10-minutes/12676570

Collyer Michael, 2012, “Deportation and the Micropolitics of Exclusion: The Rise of Removals from the UK to Sri Lanka”, Geopolitics 17(2): 276–92.

Commonwealth of Australia, 2017, “No One Teaches You to Become an Australian”, Parliament of Australia. URL: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Migration/settlementoutcomes/Report?fbclid=IwAR37A9n3SpneIVkGmJJDMcEoBraTCMTYXLlHxxEP3vdfBJ1S4GIfYre8zlU

Department of Home Affairs, 2018, “Removal from Australia - Implementing Removal from Australia: Procedural Instruction”. URL: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/foi/files/2019/fa-190900093-document-released-p1.PDF

Department of Home Affairs, 2021, “Visa Cancellation Statistics”. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/visa-statistics/visa-cancellation

Drew Christopher, 2011, “The Spirit of Australia: Learning about Australian Childhoods in Qantas Commercials”, Global Studies of Childhood 1(4):321–31.

Dunn Amelia, 2021, “Larice Has Lived Most of Her Life in Australia. But after Being Deported to New Zealand, She Feels Stuck in ‘Limbo’”. SBS News. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/larice-has-lived-most-of-her-life-in-australia-but-after-being-deported-to-new-zealand-she-feels-stuck-in-limbo

Escape, 2020, “Qantas to Fly Aussies to Antarctica during Coronavirus Pandemic”, Escape.Com.Au. Accessed 30 November 2021. URL: https://www.escape.com.au/destinations/antarctica/qantas-to-fly-aussies-to-antarctica-during-coronavirus-pandemic/news-story/3223fdc2c41afabdd7e9f502092b5dba

Gill Nick, 2013, “Mobility versus Liberty? The Punitive Uses of Movement Within and Outside Carceral Environments”, in Carceral Spaces: Mobility and Agency in Imprisonment and Migrant Detention, Moran D., N. Gill, and D. Conlon (eds.), Farnham, Surrey, Routledge.

Grewcock Michael, 2017, “Reinventing ‘the Stain’: Bad Character and Criminal Deportation in Contemporary Australia", in The Routledge Handbook on Crime and International Migration, Pickering S. and J. Ham (eds.), Routledge: 121–38.

Holman Brett, 2019, “The Militarisation of Aerial Theatre: Air Displays and Airmindedness in Britain and Australia between the World Wars”, Contemporary British History 33(4): 483–506.

Kanstroom Dan, 2007, Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History, Harvard University Press.

Karp Paul, 2020a, “High Court Rules Aboriginal Australians Are Not ‘aliens’ under the Constitution and Cannot Be Deported”, The Guardian. Accessed 11 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/feb/11/high-court-rules-aboriginal-australians-are-not-aliens-under-the-constitution-and-cannot-be-deported

Karp Paul, 2020b, “Home Affairs Department Racked up $6.1m Bill Transferring Refugees and Asylum Seekers”, The Guardian. Accessed 15 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jan/29/home-affairs-department-racked-up-61m-bill-transferring-refugees-and-asylum-seekers

Karp Paul and Davidson Helen, 2019, “Citizenship Test: Government Argues Indigenous Connection to Land ‘important’ but No Bar to Deportation”, The Guardian. Accessed 11 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/law/2019/dec/05/indigenous-citizenship-test-lawyers-argue-up-to-a-third-of-australians-at-risk-of-deportation

Loughnan Claire, 2020, “‘Not the Hilton’: ‘Vernacular Violence’ in COVID-19 Quarantine and Detention Hotels – Arena”, Arena. Accessed 25 November 2021. URL: https://arena.org.au/not-the-hilton-vernacular-violence-in-covid-19-quarantine-and-detention-hotels

Love and Thoms vs Commonwealth of Australia, 2020, Daniel Alexander Love and Brendan Craig Thoms vs Commonwealth of Australia.

McGowan Michael, 2021, “Deportation of a Minor: How a ‘corrosive’ Policy Sank Cosy Relations between Australia and New Zealand”, The Guardian. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/mar/18/deportation-of-a-minor-how-a-corrosive-policy-sank-cosy-relations-between-australia-and-new-zealand

McGuirk Rod, 2020, “Australian Court Rules Indigenous People Can’t Be Deported”, The Diplomat, February 15. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2020/02/australian-court-rules-indigenous-people-cant-be-deported/

McHardy Claudia, 2021a, “New Zealand’s Returning Offenders Act”, Border Criminologies. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2021/02/new-zealands.

McHardy Claudia, 2021b, “Punishment on Arrival: New Zealand’s Returning Offenders Act 2015”, Punishment & Society, 0(0): 1–20.

McKinnon Crystal, 2020, “Enduring Indigeneity and Solidarity in Response to Australia’s Carceral Colonialism”, Biography, 43(4), Springer: 691–704.

McNeill Henrietta, 2021, “Oceania’s ‘Crimmigration Creep’: Are Deportation and Reintegration Norms Being Diffused?”, Journal of Criminology, 0(0) : 1–18.

Milman Oliver, 2015, “Quadriplegic New Zealander Reportedly Deported by Australia”, The Guardian. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/oct/18/quadriplegic-new-zealander-reportedly-deported-by-australia

Moir Jo, 2020, “‘Do Not Deport Your People and Your Problems’ - PM Jacinda Ardern on Trans-Tasman Relations”, RNZ. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/410607/do-not-deport-your-people-and-your-problems-pm-jacinda-ardern-on-trans-tasman-relations

Moreton-Robinson Aileen, 2015, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mountz Alison, 2011, “Specters at the Port of Entry: Understanding State Mobilities through an Ontology of Exclusion”, Mobilities 6(3) : 317–34.

Mountz Alison, 2013, “On Mobilities and Migrations”, in Carceral Spaces: Mobility and Agency in Imprisonment and Migrant Detention, Moran D., N. Gill, and D. Conlon (eds.), Farnham, Surrey, Routledge: 13–18.

Mountz Alison, 2015, “Political Geography II: Islands and Archipelagos”, Progress in Human Geography 39(5) : 636–46.

National Museum of Australia, 2021, “Defining Moments: White Australia Policy”, National Museum of Australia. Accessed 23 November 2021. URL: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/white-australia-policy

NSW Museums & Galleries, 2020, “The Island | Artwork & Artist”, MGNSW. Accessed 16 May 2021. URL: https://mgnsw.org.au/the-island-artwork-artist/

NSW Museums and Galleries, 2020, “Vernon Ah Kee The Island”, MGNSW. Accessed 25 November 2021. URL: https://mgnsw.org.au/sector/exhibitions/coming-soon/ah-kee-the-island/

Paglen Trevor and Thompson A. C., 2006, Torture Taxi: On the Trail of the CIA’s Rendition Flights. First Edition. Hoboken, N.J: Melville House.

Paik, A. Naomi, 2021, “‘Create a Different Language’: Behrouz Boochani & Omid Tofighian”, Public Books. Accessed 16 May 2021. URL: https://www.publicbooks.org/create-a-different-language-behrouz-boochani-omid-tofighian/

Perera Suvendrini and Pugliese Joseph, 2015, “Dgadi-Dugarang: Talk Loud, Talk Strong A Tribute to Aboriginal Leader Uncle Ray Jackson”, borderlands e-journal 14(1):6.

Peterie Michelle, 2021, “Forced Relocations: The Punitive Use of Mobility in Australia’s Immigration-Detention Network”, Journal of Refugee Studies 34(3): 2655–75.

Pugliese Joseph, 2009, “Civil Modalities of Refugee Trauma, Death and Necrological Transport”, Social Identities 15(1) : 149–65.

Pugliese Joseph, 2015, “Geopolitics of Aboriginal Sovereignty: Colonial Law as ‘a Species of Excess of Its Own Authority’, Aboriginal Passport Ceremonies and Asylum Seekers”, Law Text Culture 19 : 84-115.

Sanchayan Kulasegaram, and Truu Maani, 2021, “These Two Children Have Now Been in Australian Immigration Detention for Three Years”, SBS News. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/these-two-children-have-now-been-in-australian-immigration-detention-for-three-years

Stayner Tom, 2020, “Experts Warn against Deportation Rush on 50,000 Plane Arrivals Whose Asylum Bids Were Rejected”, SBS News. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/experts-warn-against-deportation-rush-on-50-000-plane-arrivals-whose-asylum-bids-were-rejected).

Taylor Josh, 2021, “Keeping Biloela Family Locked up on Christmas Island Cost Australia $1.4m Last Year”, The Guardian. Accessed 13 May 2021. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/jan/07/keeping-biloela-family-locked-up-on-christmas-island-cost-australia-14m-last-year

Tofighian Omid, 2020, “Introducing Manus Prison Theory: Knowing Border Violence”, Globalizations 17(7) : 1138–56.

Walters William, 2016, “The Flight of the Deported: Aircraft, Deportation, and Politics”, Geopolitics 21(2): 435–58.

Walters William, 2018, “Aviation as Deportation Infrastructure: Airports, Planes, and Expulsion”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(16):2796–2817.

Walters William, 2020, “Inspection as Method: Using Forced Return Monitoring to Research Air Deportation”, Video recording, Border Criminologies, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v6VHn1uROYQ&feature=youtu.be&ab_channel=BorderCriminologies

Watego Chelsea, 2021, Another Day in the Colony. Univ. of Queensland Press.

Weber Leanne, 2017, “Deciphering Deportation Practices across the Global North”, The Routledge Handbook on Crime and International Migration, edited by S. Pickering and J. Ham. Routledge.

Weber Leanne and Powell Rebecca, 2020, “Crime, Pre-Crime and Sub-Crime: Deportation of ‘Risky Non-Citizens’ as ‘Enemy Crimmigration’”, Criminal Justice, Risk and the Revolt against Uncertainty, Palgrave Studies in Risk, Crime and Society, J. Pratt and Anderson J. (eds), Cham: Springer International Publishing : 245–72.

next...

Notes

23

1 Between 1788 and 1868 Australia received 160,000 forced deportees from British prisons (Hughes, 1996 in Grewcock, 2017:121).

2 One of the first pieces of legislation introduced to the newly formed federal parliament in 1901 was the Immigration Restriction Act, designed to limit non-British migration to Australia. The Attorney-General Alfred Deakin said the policy meant ‘the prohibition of all alien coloured immigration, and more, it means at the earliest time, by reasonable and just means, the deportation or reduction of the number of aliens now in our midst. The two things go hand in hand, and are the necessary complemenet of a single policy – the policy of securing a ‘white Australia’ (National Museum of Australia, 2021).

3 Wamba Wamba lawyer Eddie Synot pointed out that the judgement concerned a very narrow application of the aliens power and could not be considered a recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty.

4 Aboriginal passports were first used and accepted by a foreign country in 1988 when an Aboriginal delegation made a trip to Libya during the Australian state’s bicentenary year.

5 Uncle Ray was the founder and President of the Indigenous Social Justice Association and a tireless activist and Wiradjuri leader (Perera and Pugliese, 2015).

6 See his 2018 video work ‘The Island’: (NSW Museums and Galleries, 2020).

7 One asylum seeker described being forcibly relocated 12 times in the course of his detention (Arvin, 2021).

8 These figures were revealed by the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility under a Freedom of Information (FoI) request.

9 Alison Mountz has suggested these ‘state mobilities’ are worthy of investigation. (Mountz, 2011:317).

10 William Walters defines the term ‘deportation corridor’ as when ‘active measures are taken – legal, administrative, spatial, police, and so on – to give the [deportation] route a degree of insulation, and to ensure that it passes through places and territories in ways that anticipate and minimise interference’ (Walters, 2018:2808).

11 New Zealand Police statistics, cited in (McHardy, 2021b:2).

12 See Mountz’s work on the political geography of carceral archipelagos: (Mountz, 2015).

13 Stanley (2017) in (McHardy, 2021b:2).

14 See for example the work of Shahram Khosravi, Nathalie Peutz, and William Walters.

15 The family of four is detained in a separate facility on Christmas Island to the one that was reopened for the detainees with cancelled visas.

16 The year 2018 saw a wave of mobilisations around this issue with the Windrush scandal in the UK, the conviction of the Stansted anti-deportation activists in the UK, an announcement from Virgin Atlantic that they would stop participating in forced deportations, and a call from the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) calling on commercial airlines to stop assisting governments in deportation proceedings.

17 The resolution in 2019 was met with almost 25% support from shareholders, up from 6% support for the more ambitious 2018 resolution.

18 The coat of arms thus aligns with the theme of advancement in the national anthem – ‘Advance Australia Fair’.

19 Notably, ‘joy flights’ were a mainstay of Qantas’ business a hundred years earlier.

20 Publicly available flight tracking data has been used in the past by dedicated aviation enthusiasts to uncover top secret state practices. Perhaps the most famous example, the plane-spotters who unwittingly uncovered the CIA’s program of extraordinary rendition through noticing unusual behaviour of four suspicious planes. See (Paglen and Thompson, 2006).

Return to the beginning of article...

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-05-smith-air-deportation-and-the-settler-colony.pdf

Activists leafleting outside the Qantas stall at the 2019 Mardi Gras. Photo: No Pride in Protest.