antiAtlas Journal #5 - 2022

Frontex as a symptom of the EU’s “deportation syndrome”

Sarah Zellner

Abstract: Frontex facilitates European states’ air deportations, increasing the scope of national executives and adapting to national deportation infrastructures. The article also demonstrates how the agency is embedded in an EU system that sets deportation targets and assesses the agency in numbers. Ultimately, it documents a polymorphous air deportation infrastructure where national, bilateral and European pathways intersect to exclude people on the move.

Sarah Zellner holds an MA in Political Science from the University of Freiburg and Sciences Po Aix, as well as an MSc in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies from the University of Oxford. Her interest for migration control policies stems from years of working alongside people on the move.

Keywords: Frontex, air deportation, Europeanisation, human rights, migration.

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportations"

Directed by: William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

Photo illustrating a Frontex press release on the first Frontex-supported “voluntary” Joint Return Operation in 2020, Frontex, 2020a. The choice of motif, the sun recalling a happy holiday departure, illustrates the way in which so-called voluntary return is euphemised by the authorities, including Frontex.

To quote this article: Zellner, Sarah, "Frontex as a Symptom of the EU's 'Deportation Syndrome'", published on June 1st, 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL: www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-zellner-frontex-as-a-symptom-of-the-eu-deportation-syndrome, last consultation on Date

Introduction

1 Recently, the European Border and Coast Guard agency has once again come under public scrutiny regarding its involvement in systematic push- and pullbacks at the European Union’s (EU) external borders – where people are violently denied the right to claim asylum (Christides et al., 2021; Cossé, 2021; Frontex Scrutiny Working Group, 2021). Currently less discussed than the agency’s role at the EU’s sea and land borders is its involvement in the EU’s air deportations (Gkliati, forthcoming). While Frontex’s role at the borders warrants continued attention, it is also relevant to examine the agency’s involvement in air deportations in view of two recent expansions of its mandate in this regard, which transformed Frontex into a “returns agency” (Carrera et al., 2017: 47).

A frequently changing air deportation infrastructure

This article explores the role of the European Border and Coast Guard agency – hereafter referred to by its acronym Frontex or “the agency” – within the EU’s air deportation infrastructure. I focus on how EU member states and Schengen associated countries use Frontex’s support for their deportations via charter flight and the interactions between member states and the agency. This research began at the end of 2019 with an exploratory study on Frontex’s role in organising charter flights. Charter flights are deportations by special aircraft without regular passengers on board, and support for their organisation was part of Frontex’s original mandate (Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004 [2004] OJ L 349). The first Frontex regulation tasked the agency with assistance in Joint Return Operations (JROs), joint charter flights of several European countries, all deporting on the same aircraft. In addition to assistance with JROs, the initial regulation also mentioned the identification of “best practices” in obtaining travel documents and “return” and training courses in “return” for member states officials (ibid.). While I mostly discuss charter flights, my research also documented a frequently changing air deportation infrastructure. I lack data on the agency’s “pre-return” support, which could be explored in more detail in future work.

next...

2 Although there is already an extensive literature on Frontex, some of its activities remain largely unexplored. A systematic literature review notes that “some tasks have received limited empirical attention (e.g. implementation of forced returns) and almost all activities are studied based on documentary data, so that ethnographic research and interview data sets may help us to better grasp how Frontex personnel translate policies into practice” (Kalkman, 2021: 169). This article contributes to addressing these gaps as it studies the agency’s involvement in air deportation based on documentary data as well as interview material. Recently, there have been several insightful reports on Frontex and air deportation, illustrating the emerging interest in this topic. Pascaline Chappart (2019; 2020) has shown, inter alia, that attempts at the practice of joint European deportation flights predate the existence of the agency. Statewatch’s report (Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020) as well as their Frontex Observatory provide rich sources for future research, as the researchers have compiled a publicly available database on charter deportations coordinated by Frontex. One of the authors of the Statewatch report, Mariana Gkliati (forthcoming), has discussed human rights implications of Frontex’s expanded mandate on “return”. There have been several reports within the project “Advancing Alternative Migration Governance” (ADMIGOV) (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021; Kalir et al., 2021) that have shed light on different member states’ usage of Frontex. However, their report dedicated to Frontex (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021) is predominantly based on interviews with Danish and German officials, whereas the present article draws on other countries’ experiences and a different database.

This article contributes to addressing these gaps as it studies the agency’s involvement in air deportation based on documentary data as well as interview material

This article speaks to several debates in the literature, firstly the Europeanisation of migration policies, secondly deportation studies and thirdly the limits of state deportation policies. Europeanisation literature “aims at understanding how national policies are shaped and changed due to European integration” (Ette, 2017: 50). As Florian Trauner and Ariadna Ripoll Servent (2018: 12) state, “we need more research on how EU policy outputs become outcomes; that is whether and how implementation occurs in a practical manner”. There is a broad consensus in Europeanisation literature that this process strengthens national executives. At times, scholars have argued that some European institutions can also impose “liberal” constraints on member states (Bonjour, Ripoll Servent and Thielemann, 2017; Slominski and Trauner, 2014; Ette, 2017). Loosely inspired by Peter Slominski and Florian Trauner’s (2018) work, I focus on usages and non-usages of Frontex’s “offer” by member states. This article is concerned solely with practices, and not legislative changes at the national level.

next...

3 I argue that Frontex facilitates air deportations of European states, increasing the scope of action of national executives and adapting to national deportation infrastructure. While the Europeanisation of migration control affects national deportation infrastructure, national and bilateral practices still prevail under the Frontex label. Member states appropriate the “Frontex offer” in different ways. Rather than explaining these differences, this article sheds light on how the EU’s air deportation infrastructure operates. The “super-agency” Frontex is embedded in an EU system requiring it to be efficient and effective. Ultimately, the article documents a polymorphous infrastructure where national, bilateral and European pathways intersect to exclude “unwanted migrants”. The term “unwanted migrants” is taken from Slominski and Trauner’s (2018) work. I consider it symptomatic of how European authorities approach people on the move.

National, bilateral and European pathways intersect to exclude “unwanted migrants”

In what follows, I address methodological considerations, as I consider the difficulties that I encountered to be a result in themselves. I then synthesise the expansion of Frontex’s legal mandate to document the evolving air deportation infrastructure. The next section discusses how various countries use Frontex’s “offer”, demonstrating both the prevailing differences between states and the circulation of practices to show how Frontex increases national executives’ scope of action. I then explore how Frontex’s practice is situated within an EU system requiring it to be both efficient and effective when deporting people on the move, while highlighting that Frontex also depends on certain member states for the agency to appear “effective”. In conclusion, I argue that Frontex’s changing mandate and the way it is appropriated by member states is symptomatic of a continuously evolving deportation infrastructure.

next...

Researching a secretive environment

4 This research relies on interview data, legal sources and reports by European bodies, national authorities and NGOs. In contrast to most existing studies, I conducted 26 semi-structured interviews with 30 interviewees, including staff from the French Ministry of Interior, the French border police and Frontex. I met with parliamentary assistants and political advisors in the European and the German Parliament, who worked on the Frontex regulations, as well as NGO representatives, including a former member of the Frontex Consultative Forum. The Consultative Forum is composed of EU agencies, international organisations and NGOs and is meant to advise Frontex on human rights, although this is made difficult as the Forum lacks capacity, time and receives insufficient information from the agency (Karamanidou and Kasparek, 2020: 7, 47-48). The Belgian Ministry of Interior answered my questions in writing. I draw on access to information requests to the agency made for this research project and public as well as leaked documents. My analysis is thus largely based on northern member states, although I refer at times to others. This article focuses exclusively on air deportation and mostly on charter flights, not on operations at the EU’s sea or land borders or in non-EU countries. It thus does not address Frontex’s role in pushbacks and pullbacks during these operations, which I could not do justice to. I concur, however, with Martin Lemberg-Pedersen and Oliver Joel Halpern (2021: 19) who problematise the clear-cut distinction between “return” and push- and pullbacks.

A “successful” deportation flight might be publicly announced, but its modalities are frequently obscured

Researching deportations is difficult in a multitude of ways. While authorities do not hide deportations altogether – after all, they have an important communicative and symbolic function (Le Courant, 2018) – their visibility is essentially contested. A “successful” deportation flight might be publicly announced, but its modalities are frequently obscured. Public reports are manicured and omit much concrete information, “reproduc[ing] people as a technical problem” (Reid-Henry, 2013: 217). While interview data goes beyond these accounts, I rely on the willingness of my interlocutors to share information and triangulated information from different sources. It seems that charter flights are especially difficult to research because of their contested nature (Walters, 2016). They are controversial because of the absence of “regular” passengers, their deterrent function, the association with collective expulsions prohibited under international law and the cost imperative of “rentabilising” charter flights that may lead to “round[ing] up all these people in a short time to be able to put them on this charter” (Representative of the NGO La Cimade, interview and translation by the author, February 2020). When comparing statistics from different sources on deportations, they rarely match. There are differences between statistics released by Frontex in access to document requests or in reports, statistics in the database Statewatch compiled based on their access to document requests to the agency, Eurostat data and data published by national authorities or researchers. I rely mostly on statistics obtained directly from the agency through access to document requests.

next...

5 Frontex documents are accessible through access to document requests under Regulation 1049/2001 ([2001] OJ L 145). According to Article 7 of the regulation, “[a]n application for access to a document shall be handled promptly”. However, such requests may take several weeks or even months. Some of the documents I received were so redacted that they had little informational value other than conveying that something should not be disclosed. For example, I requested all “Monthly Analyses for Return” (26 documents in total), each of which being four pages long. More than two pages per report were fully expunged. According to Frontex’s justifications, personal data, operational data or information relating to cooperation with non-EU countries, amongst other things, had been removed. Access to Frontex documents has become even more difficult, as the agency has started operating its own portal for access to information requests, instead of answering requests directly on platforms like “asktheeu”, where released documents remain publicly available. The agency claims to have a copyright on released documents, prohibiting any publication without its prior authorisation. This is counter-intuitive as these documents were released to fulfil transparency obligations under EU law. Finally, the format of many of the released documents, as unsearchable pdfs, contributed to the difficulties of analysing the agency’s statistics. It seems that access to Frontex, including for interviews, has become more challenging over time, in particular when the agency’s press office is involved. Immediately before submitting this article for publication, the Frontex press office prohibited me from quoting directly from an interview with a senior Frontex official. Previously, the press office had insisted on being shown the draft article. The interview supports the main conclusions of this article (for similar difficulties: Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021: 15-19).

Immediately before submitting this article for publication, the Frontex press office prohibited me from quoting directly from an interview with a senior Frontex official

next...

Fig. 1: The disclaimer Frontex adds in all its responses to access to document requests, Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

6 My research is limited by this lack of information. Moreover, my interview period was close to the entry into force of the agency’s last mandate at the end of 2019 (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896 [2019] OJ L 295). It is therefore not surprising that the agency is still in the process of implementing the latest regulation at the time of writing, given the increase in its prerogatives. Much of their operations is in flux, also because new EU plans and communications on “return” have been adopted in the meantime. Finally, there were many actors I could not speak to, most importantly deportees themselves. This makes it difficult to show the impact that deportations have on those affected. Each deportation, no matter what form it takes, is a brutal intervention in the life of an individual. Only NGOs, media sources and monitoring reports provide insight into the sociological profile of those deported or the violence perpetrated during deportations (cf. the Cimade’s (2019) report on the police’s violent interpellations during a Frontex-coordinated deportation flight to Georgia).

I refrain from using the term “return” and use “deportation” or “(forced) removal” instead, except for terms in the Frontex regulations, such as “Joint Return Operation” or when referring to what is labelled as “voluntary” return. I conceive of “deportation” as a synonym for “forced removal” (Majidi and Schuster, 2019: 89). While the term “return” is continuously used by authorities, it has a euphemistic function, as it normalises return as an “inherent component” of migration (Genova, Lecadet and Walters, 2018) and obscures the differences between genuine return and forced removal (Cassarino, 2020). The term “return” also evokes falsely positive associations as it is considered one of the three durable solutions for refugees, next to resettlement and local integration (Chimni, 2004; Majidi and Schuster, 2019). Therefore, I refer to removals as “deportations” instead of assuming that “return” would be an appropriate term, even though Frontex’s mandate has included so-called “voluntary departures” since 2016 and “voluntary returns” since 2019.

next...

The Agency's Mandate: an ever-evolving deportation infrastructure

7 The last two Frontex regulations, adopted in 2016 and 2019, illustrate the will of EU legislators to expand the agency’s capacities, including with regard to air deportations. The agency’s mandate has increased from its beginnings in 2004 to in 2019 being capable of supporting any form of deportation-related task, with the exception of the return decision, which remains the sole responsibility of member states (Frontex, 2021a: 9). This allows for a division of responsibility between the agency and states. It seems that “integrated border management” is what EU legislators can agree upon, in contrast to other forms of cooperation within Justice and Home Affairs (for a broad overview of Frontex’s mandate: Meissner, 2021). However, several times, the legislation has only formally codified what Frontex had already started to do in practice (Chappart, 2019; Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020). This non-exhaustive presentation of the mandate with regard to air deportations provides the background to the following sections (for more details: Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021; Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020).

The agency’s mandate has increased from its beginnings in 2004 to in 2019 being capable of supporting any form of deportation-related task

next...

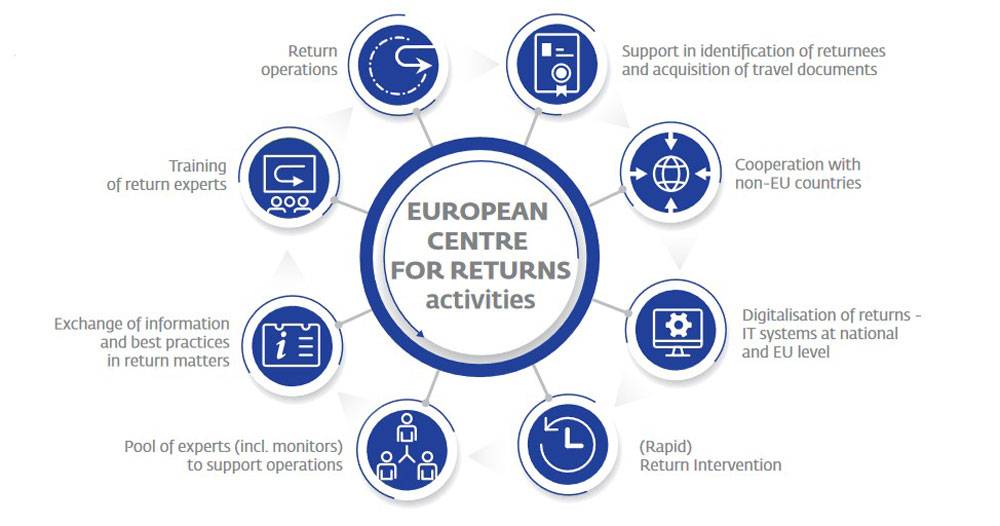

Fig. 2: Self-presentation by the agency’s European Centre for Returns. Graphic, Frontex, 2021b. Technical, efficient and diverse: the graphic is illuminating both in terms of the variety of activities that the European Centre for Returns has assembled and, much more importantly, the way it represents deportations as a neutral process. Deportations are optimised by an agency forming “pools of experts”, sharing “information” and “best practices” and “digitalising”. As with Frontex’s general communication, it is difficult to decipher the impact on people of it all behind the arrowed icons and manicured communication packages.

8 Whereas Frontex has become the symbol of a shift towards charter deportations (Chappart, 2020), Frontex’s mandate now covers support for every form of air deportation – forced and “voluntary” (see figure 3 below), via charter and scheduled flight. The latest Frontex regulation stipulates that the agency should “provide assistance at all stages of the return process” (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Art. 10), even post-return assistance (ibid., Art. 48). Thus, the agency covers not only operational support for the deportation flight itself. It is also involved with “pre-return”, such as the identification and documentation of non-EU nationals as well as the digitalisation of removal procedures through the development of European and national platforms, communication infrastructures and return management systems (ibid., Art. 48). The agency’s positioning at the centre of the EU’s “return management” (ibid., Art. 48) is also evident in that it is taking over several intergovernmental and EU-funded projects, namely EURINT (European Integrated Return Management Initiative), ERRIN (European Return and Reintegration Network) and EURLO (EU Return Liaison Officers) (Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020: 31).

next...

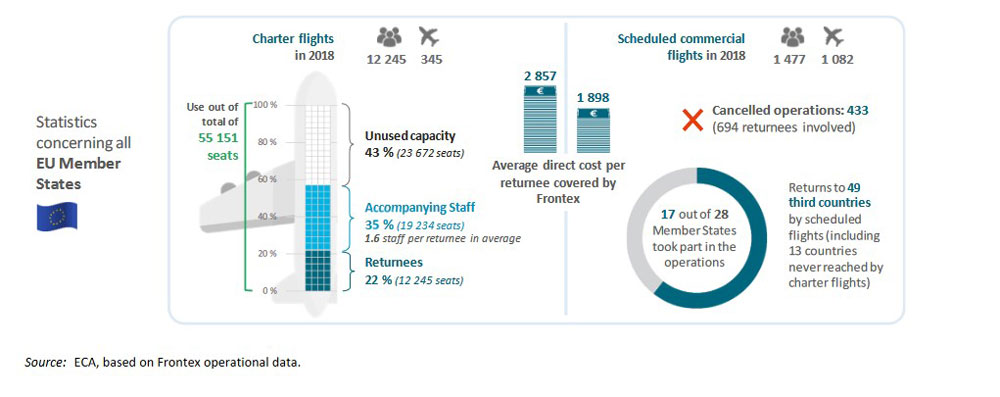

9 When comparing charter and scheduled flights, most air deportations coordinated by Frontex are still carried out via a charter flight (Frontex, 2021a: 57), although the agency supports more and more regular flights. Scheduled flights amounted to 40% of all Frontex-supported air deportations in the first half of 2021 (Frontex, 2021d: 4). As results from my interviews, this means that government officials can book flight tickets for removals via scheduled flight through the Frontex Application for Return (FAR), a communication infrastructure developed by the agency. These tickets are paid for by Frontex. For charter flights, the agency also covers a large part of the cost. In addition, a representative of the agency is often present on board. The agency can charter aircrafts for such flights. Prior exchanges between states and the agency, but also inter-state exchanges, are carried out through FAR. Since 2016, the agency has been mandated to establish pools of return escorts, return monitors and return specialists (deployed by member states) (Regulation (EU) 2016/1624 [2016] OJ L 251, Arts. 29-31) for return operations and interventions. The 2019 regulation again changed this structure due to the establishment of a permanent corps of 10,000 members by 2027, including 3,000 statutory Frontex staff. The permanent corps and part of the statutory staff also include forced return escort and support officers as well as return specialists. The agency will thus have its own staff for air deportations. Whereas the forced return monitors are still deployed from the pool, there will also be 40 Frontex fundamental rights officers that could be deployed for air deportations (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Arts. 5, 55, 110, Annex I; Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020).

next...

Fig. 3: Photo illustrating a Frontex press release on the first Frontex-supported “voluntary” Joint Return Operation in 2020, Frontex, 2020a. The choice of motif, the sun recalling a happy holiday departure, illustrates the way in which so-called voluntary return is euphemised by the authorities, including Frontex.

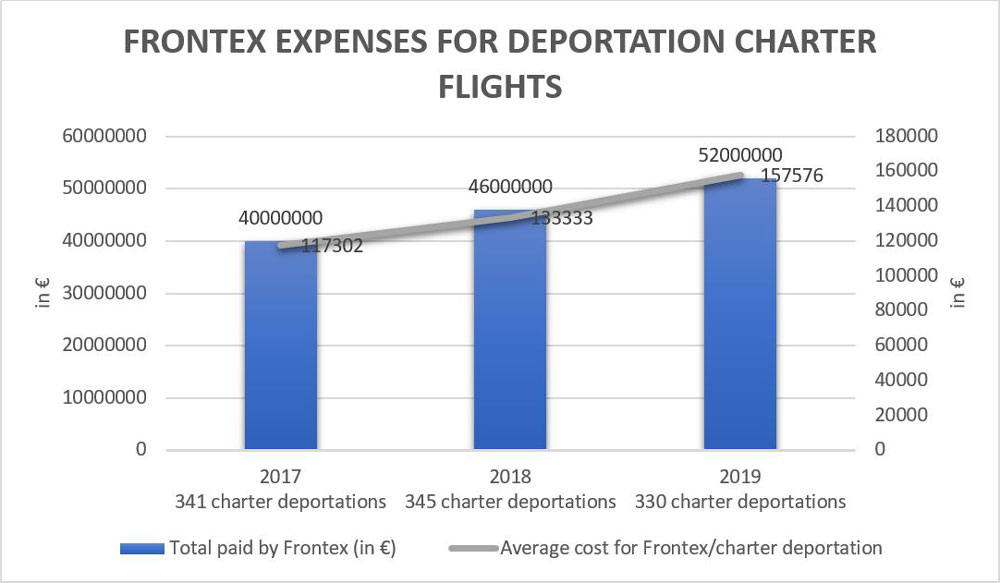

Fig. 4: Average cost per Frontex-coordinated charter flight paid by the agency. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on a graphic released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020

10 As far as charter flights are concerned, the mandate of the agency has been broadened. Since its first mandate, the agency has supported Joint Return Operations (JROs), where several European states all deport on one aircraft. Since 2016, Frontex’s mandate has also included National Return Operations (NROs), where “only” one country deports, and Collecting Return Operations (CROs), where the non-EU country “collects” its own citizens with its own escorts and/or aircraft. However, the agency’s support for NROs and CROs predates its legal basis (Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020), which is just one example of how the agency’s practices have been formalised later by EU legislation. For each charter flight coordinated by Frontex, there is an Organising Member State (OMS). If other countries participate in the operation with deportees, these are called Participating Member States (PMS). If Frontex organises the flight itself, there must still be a Lead Member State. There has also been a gradual evolution towards more initiative for the agency, which speaks to the general trend in the legislation of increasing the agency’s autonomy. Initially the agency could “provide […] assistance” for deportation flights (Council Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004, Art. 9), then coordinate and organise them (Regulation (EU) No 1168/2011 [2011] OJ L 304, Art. 9) and finally propose return operations to member states (Regulation (EU) 2016/1624, Art. 28). These terms, however, have never been defined in the mandate, which allowed for interpretation by the agency. For example, in 2015 the agency “invited” Greece to conduct a deportation charter flight to Pakistan (Frontex, 2015b), although it was only competent to initiate such flights from 2016 onwards.

With regard to cooperation with non-EU countries and air deportations, the agency has been able to deploy its own liaison officers to non-EU countries since 2011 (Regulation (EU) No 1168/2011, Art. 14). Since 2016, the agency has been able to assist in obtaining travel documents and identifying non-EU nationals (Regulation (EU) 2016/1624, Art. 27). However, member states’ experts and Frontex officers had already been sent to other member states for “return capacity building”, such as identification and documentation, during previous Frontex-coordinated operations at the EU’s external borders, for example in Greece, Spain, Malta or Bulgaria (Frontex, 2007: 12-13; Frontex, 2010: 26-27; Frontex, 2011: 37; Amnesty International and ECRE, 2010: 11-12). The Commission’s proposal for the 2019 regulation to allow Frontex to conduct deportations from non-EU countries to other non-EU countries not bound by EU law (e.g. from Serbia to Afghanistan) was dropped in negotiations with the European Parliament. This notwithstanding, as show Frontex documents (2019), the agency has long been active in non-EU countries involving activities related to deportations, such as “support[ing] target countries in bringing identification and screening procedures into their national systems”.

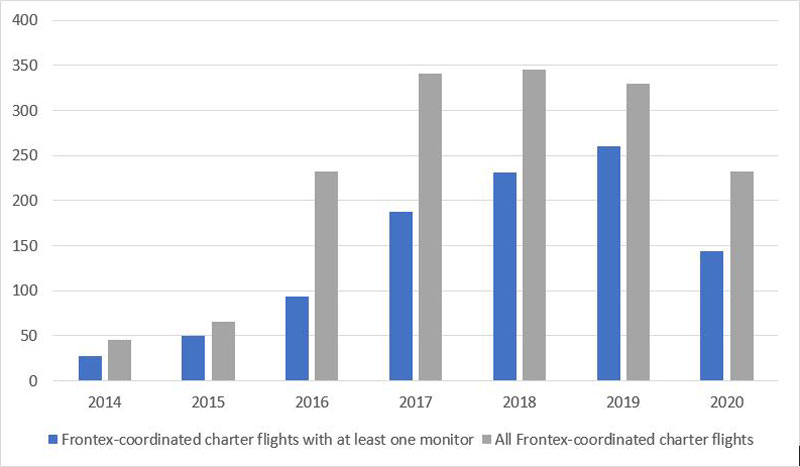

The agency’s mandate expansion has contributed to an increase in removals (via charter and scheduled flights) supported by the agency

Overall, the agency’s mandate expansion has contributed to an increase in removals (via charter and scheduled flights) supported by the agency. “In 2015, out of the 72,839 people who were returned in a forcible manner [from the EU to a non-EU country], less than 5 per cent were subject to a joint EU return operation” (Slominski and Trauner, 2018: 108). This has changed to some extent due to the stark increases in Frontex-supported deportations via charter flight in 2016 and, again, in 2017. This notwithstanding, Frontex-supported “return operations” via both charter and scheduled flight remain a fraction of member states’ removals, accounting in 2019 for 10% and in 2020 for 20% of all “effective returns” from the EU to non-EU countries, according to the agency (Frontex, 2021a: 29). However, these EU figures on “return” should be treated with caution as they vary widely. It is unclear on what data they are based, these figures do not account for illegal pushbacks at borders, and these statistics are not apolitical but are used by authorities to claim the “ineffectiveness” of migration control policies and call for increasingly restrictive policies (Carrera and Allsopp, 2018).

next...

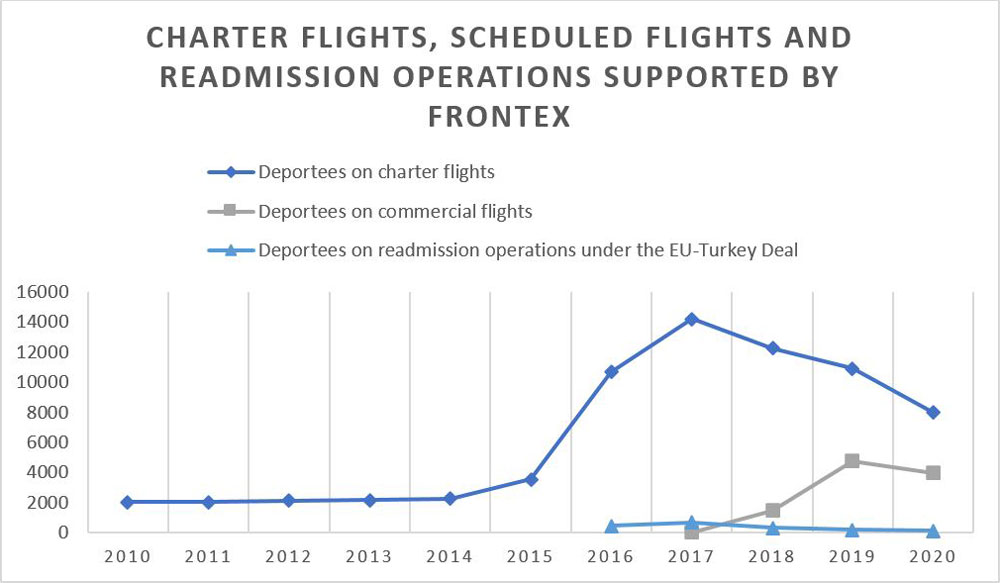

Fig. 5: Charter flights, scheduled flights and readmission operations supported by the agency. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Frontex Annual Reports 2010-2020.

Usages and non-usages of Europe: illustrative examples

11 Little is known about how member states deport “unwanted migrants” (Slominski and Trauner, 2018: 101). It is not clear from the agency’s communications alone what it means when it “coordinates” or “organises” charter flights, nor how certain practices circulate between states and the agency, or how deportation routes and corridors are shaped and routinised. This section argues that the expansion of the agency’s mandate – both through an extension of the legal mandate and through its own interpretation, which often preceded the legal codification – has enabled the adaptability of the “Frontex offer” to the air deportation infrastructure in member states. This overview highlights some key aspects of Frontex’s use by member states, but is by no means exhaustive (see also Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021: 33-43). As mentioned at the outset, I focus mostly on Frontex-coordinated charter flights. When analysing the data on Frontex-coordinated removals, it becomes clear that the “Frontex offer” is taken up to varying degrees by member states. National officials may pick and choose from Frontex’s offer and complain that some “services” are not useful. Some states, such as Denmark, make less use of the agency because they perceive it as inappropriate in the Danish context (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021). In the following, I discuss illustrative counter-examples, based on Frontex statistics for the years 2017 to 2019.

next...

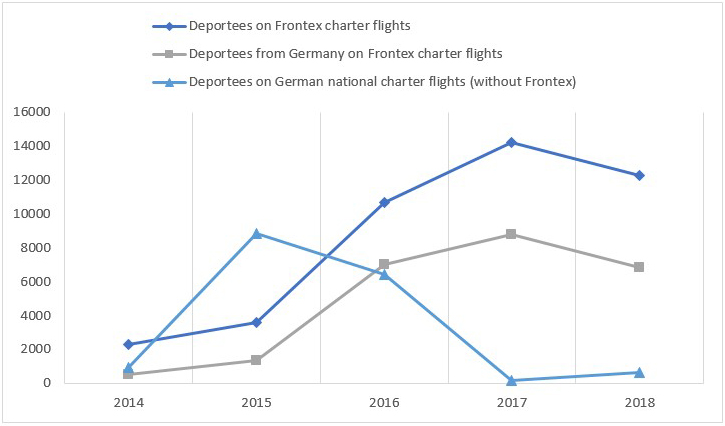

12 Overall, when considering charter flights, Frontex has become a German deportation agency. Germany’s use of the “Frontex offer” reflects the increase in Frontex-supported air deportations. While the number of Frontex-coordinated deportations via charter flight remained relatively stable until 2015 (Slominski and Trauner, 2018: 108), this changed in 2016.

When considering charter flights, Frontex has become a German deportation agency

Whereas Germany deported 1327 people on Frontex-coordinated charter flights in 2015, 7041 people werde deported from Germany on Frontex-coordinated charter flights in 2016, 8808 in 2017 and 6808 in 2018. The agency financing National Return Operations (NROs) from 2016 onwards is important in explaining this increase (3656 deportees from Germany on Frontex-coordinated flights that included only deportees from Germany in 2016), but not solely, as Germany’s use of Joint Return Operations (JROs) also increased dramatically (3385 deportees from Germany on Frontex-coordinated flights with deportees from several countries in 2016) (Bundesregierung, 2019; Frontex, 2019c; Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020).

next...

Fig. 6: The trend in the number of deportations from Germany on Frontex charter flights mirrors the trend in deportations on all charter flights coordinated by Frontex. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Frontex Annual Reports 2014-2018; Bundesregierung, 2019; Frontex, 2019c and data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

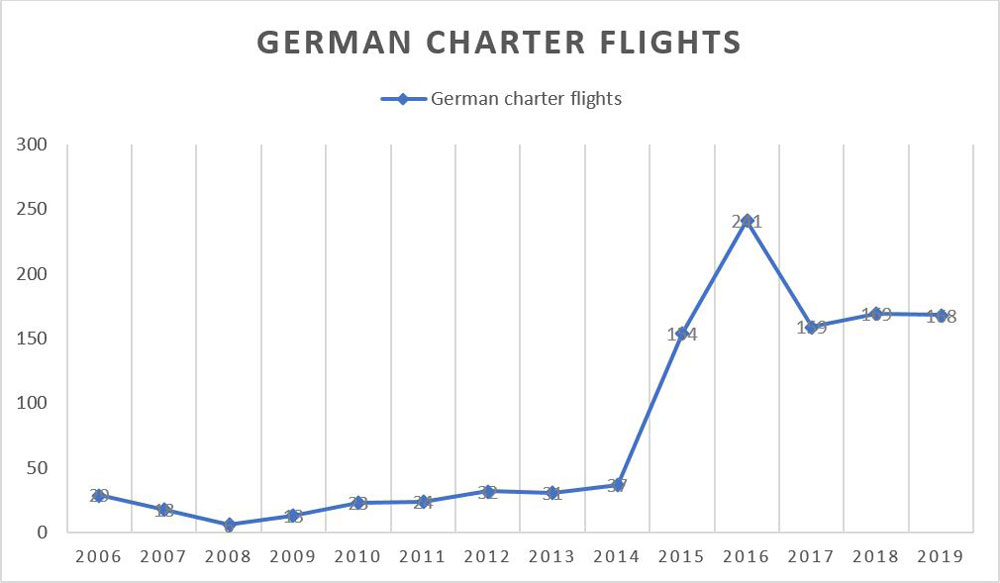

13 Although Germany relies heavily on Frontex and on charter flights as a tool for large-scale and targeted deportation, this has not necessarily led to an increase in deportees removed on charter flights from Germany (German term: Sammelabschiebungen, German figures only cover flights labelled by the government as Abschiebungen). It appears that Germany had already organised numerous charter deportations at the national level in 2015 without Frontex support. When Frontex began funding single-country charter deportations in 2016 (National Return Operations (NROs)), Germany started relying on Frontex for almost all of its charter deportations (Sammelabschiebungen) from 2017 onwards (Bundesregierung, 2019: 5) (as stated before, there are small national charter deportations that do not appear in the government’s data). Many of the flights that appear in the Frontex statistics as Joint Return Operations (JROs) organised by Germany are deportation flights with only deportees from Germany on board. In 2017, for example, out of the 69 JROs organised by Germany, only 10 included deportees from other member states (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020). Frontex statistics can be misleading in this regard. From 2016 onwards, the agency counted flights involving more than one country as JROs, for example when another country provided a monitor (even if “only” one country was deporting on that flight). In 2020, the agency again changed its statistics and only counted charter flights involving deportees from more than one country as JROs. Whereas the German example illustrates thus a certain “re-nationalisation” of the joint charter flight, Germany also frequently participates with deportees in JROs organised by other European countries.

next...

Fig. 7: Germany has increasingly relied on charter deportations for forced removals from 2015 onwards (German: Sammelabschiebungen, these figures on charter flights only cover Abschiebungen, not including Zurückweisungen (at the border) and Zurückschiebungen). Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Bundesregierung, 2020.

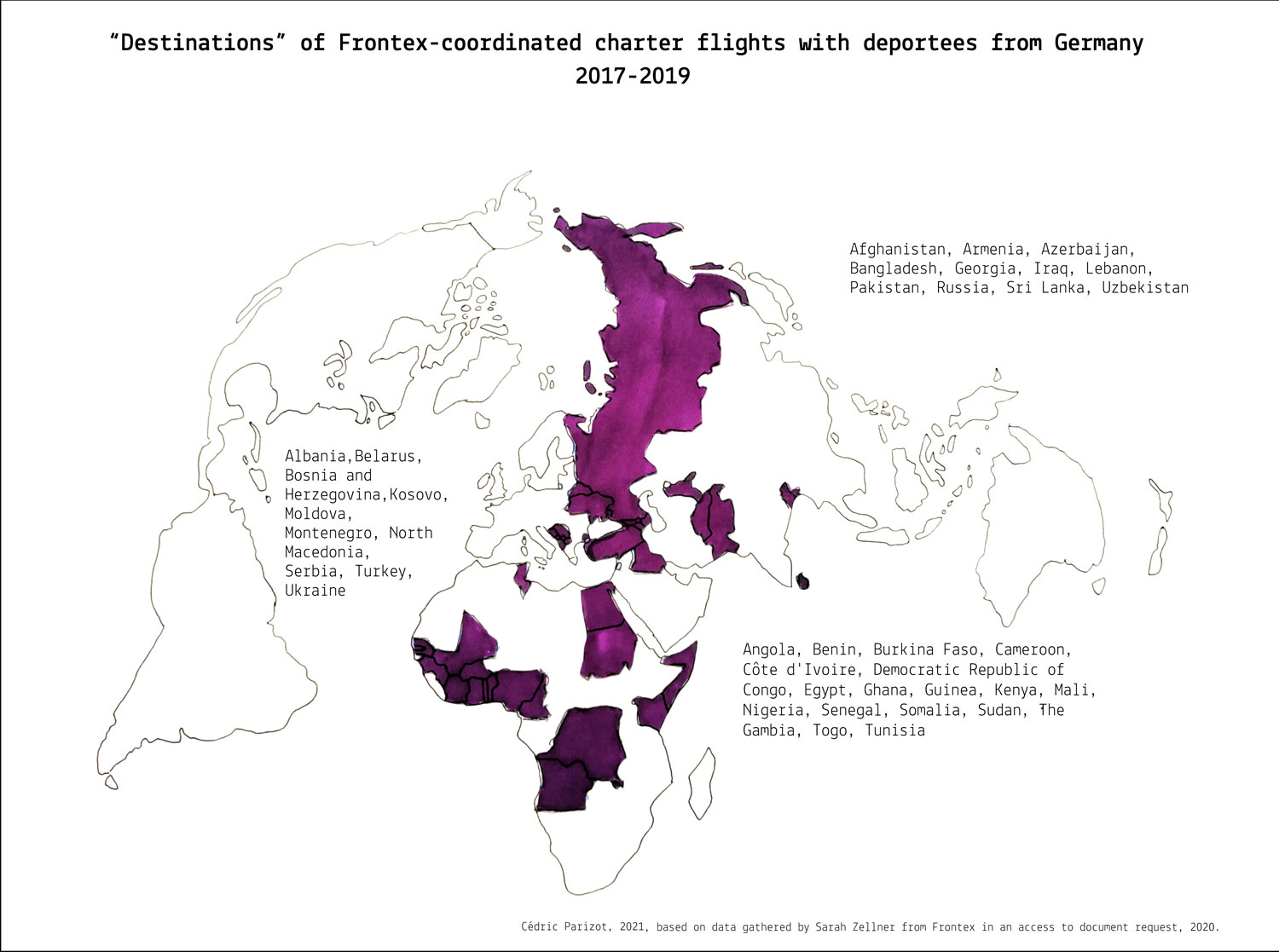

14 With Frontex support, Germany organises both very large charter flights with more than hundred deportees, to the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe, but also extremely small charter flights. What is remarkable is how in recent years Germany has organised Frontex-coordinated charter deportations to more and more countries, including many countries facing conflict, such as Afghanistan and Somalia (Statewatch, 2020). Future research could explore whether the agency’s involvement, and in particular it financing charter flights, might have influenced this German focus on charter flights as a deportation instrument and the increase in “destinations” of Frontex-coordinated charter flights organised by Germany in recent years (see figure 8).

next...

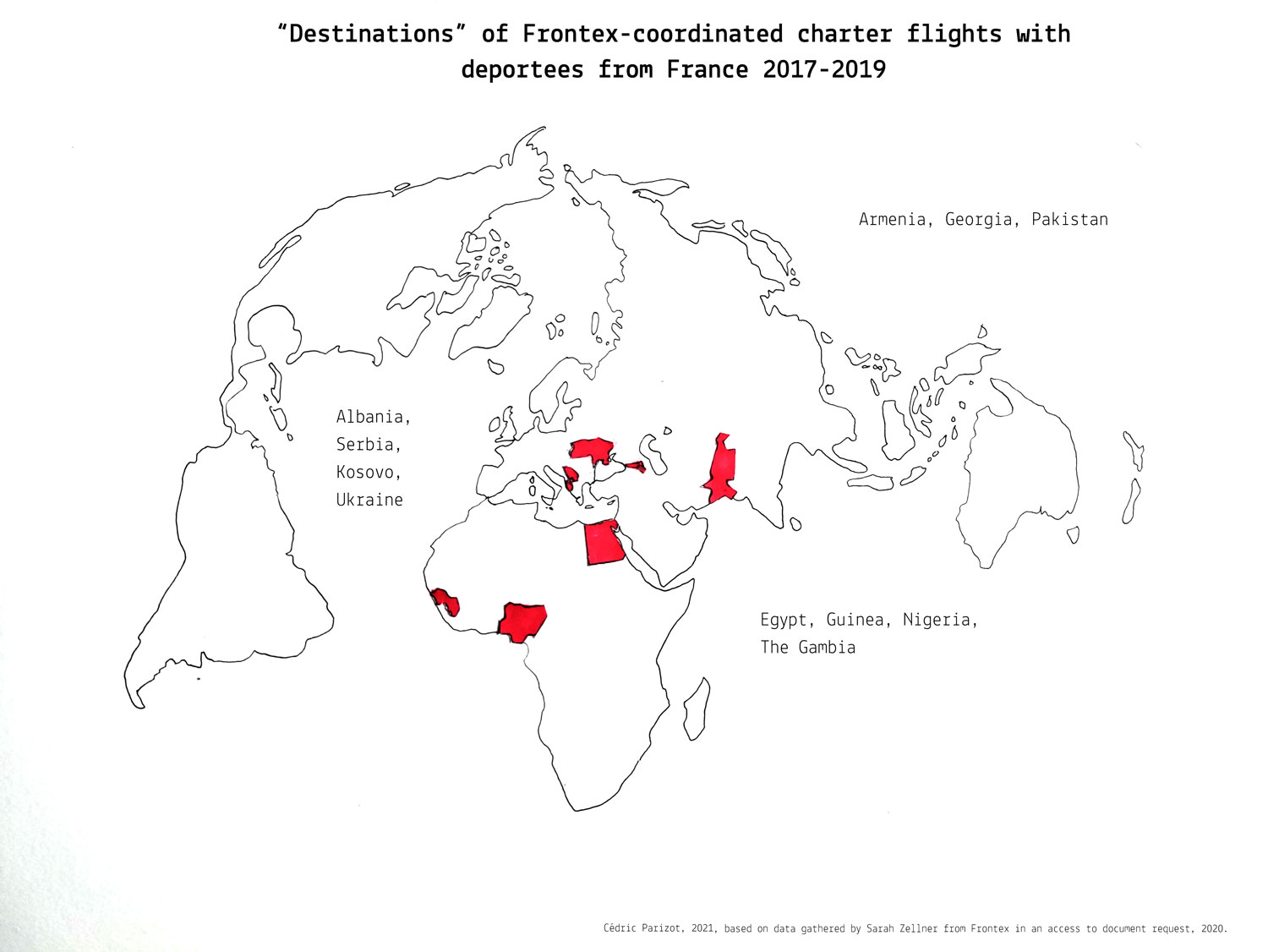

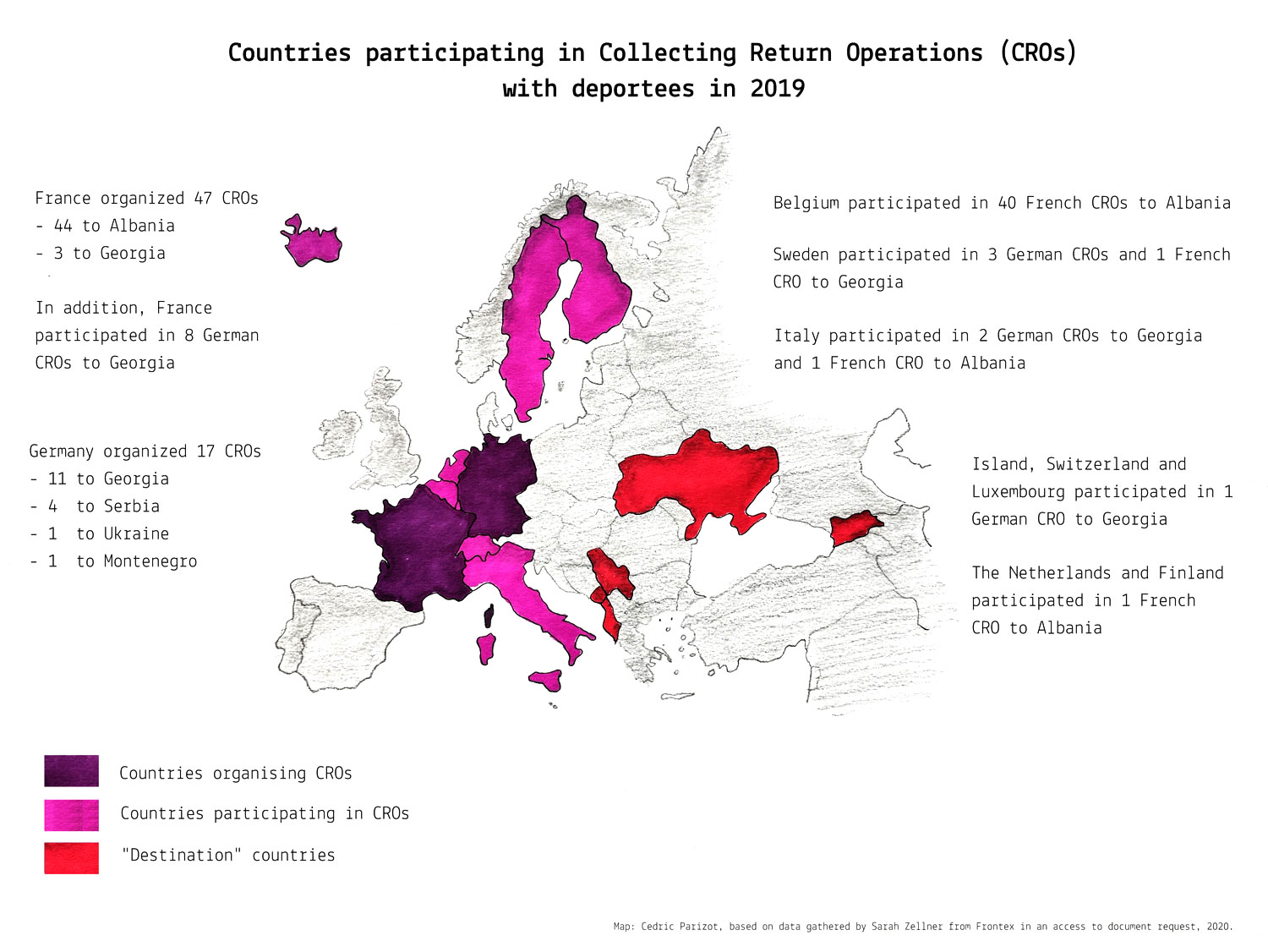

15 An analysis of France’s use of the agency (2017-2019) gives a very different picture, where a routinised deportation route stands out. In numbers, France’s use of the “Frontex offer” is not comparable to Germany’s. In 2018, France deported 1,075 people on Frontex-coordinated charter flights (DCPAF, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020). However, the French example foregrounds a specific deportation practice. Starting in 2017, France organised an almost weekly deportation flight to Albania, frequently with several deportees from Belgium and taking the form of a Collecting Return Operation (CRO). Apart from France, in the examined time period (2017-2019), Germany is the only other country regularly organising CROs, although other states, and most notably Belgium, participate in these flights (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020; French police officers, interviews by the author, February and March 2020).

“The flights that we organise on a weekly basis in Lille, their primary purpose is to decongest the Calais area, which is suffering [...] from very high Albanian migratory pressure [...] and these weekly flights mainly concern single adults who are going to be checked in the Calais region, placed in detention in Calais or Lille [...]. Major Y [...] is able to deal every week with around twenty cases of Albanians stopped in the previous days and detained [...] in the Calais detention centre” (French police officer 1, interview and translation by the author, March 2020).

"[I]f tomorrow I were asked to organise a flight to Georgia, I wouldn’t have enough Georgians to make the plane profitable"

While France only occasionally participated in charter flights organised by other countries in the examined period, this interviewed French official’s quote captures well their rationale:

“[W]e can benefit from a large aircraft chartered by a neighbouring country without having to charter a large aircraft, in order to regularly organise the departure of 5 or 6 people. [...] So my colleague is finalising a French participation in a German flight which will take place on 5 March, and the next ones which will take place on 23 April, 19 May and 4 June [...] will finally allow us [...] to remove [...] about twenty Georgians. These are Georgians who will be taken from the detention centres. […] [I]f tomorrow I were asked to organise a flight to Georgia, I wouldn’t have enough Georgians to make the plane profitable” (French police officer 1, interview and translation by the author, March 2020).

next...

16 Collecting Return Operations are charter flights in which the non-EU country “collects” its own citizens in its own aircraft and/or with its own escorts. They thus involve not only coordination with the other deporting states and Frontex, but also the outsourcing of the deportation itself to the non-EU country, under the gaze of a monitor, and a representative of the Organising Member State (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Art. 50). Given the highly asymmetric interest in deportation between the deporting and the “receiving” country (Coleman, 2009), it is not surprising that CROs have only been organised to a limited number of countries. These all have a particular interest in cooperating with the EU, namely Albania, Georgia, Serbia, Ukraine, Macedonia and Montenegro (Point de contact français du Rem, 2018; Gkliati, forthcoming). When these operations first occurred with Frontex support, they were presented by the agency as “the new way of return” (Frontex, 2014: 18). They are presented as a miracle solution in terms of costs, organisational efforts (no work on landing permits), and, in particular, no need for national escorts. They are also euphemised in terms of transmission of “European” standards and communication between the escorts and the deportees (Frontex, n.d.a). According to the agency, this concept emanates from member states, but it has been generalised by the agency that trains escorts for participation in these CROs, most recently Moldavian escorts (Frontex, 2021a: 60-61). Apparently, the first such flights under Frontex coordination were organised by Germany to Georgia in 2013 (Frontex, 2016a). Since then, France and Germany have become the main countries organising CROs. For French officials (interviews by the author, February and March 2020), this deportation practice has been developed by the agency, and the outsourcing of the deportation to third country escorts is perceived as their key advantage. In the words of one French official,

“[t]hese are flights that are entirely financed by Frontex, [...] which Frontex has also made agreements with the countries of origin, so with escorts from the country [...] of origin [...]. [...] And these high-capacity flights [...] are very interesting for us, firstly because it is less demanding on the police force insofar as there are escorts from the countries of origin, and secondly, we have a guarantee of respect for human rights because Frontex takes on board a doctor, a [...] sort of ombudsman, a defender of rights, dependent […] on Frontex, who ensures that all operations are carried out with respect for […] people’s rights, a translator and representatives of the host countries [...] and representatives of diplomatic authorities [...]. And then in terms of […] cost […], these are generally […] large aircraft. In terms of cost, [...] it actually relieves the […] national budget” (Official in the French Ministry of Interior, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

Non-EU country “collects” its own citizens

For deportation scholars, this practice might not appear unprecedented as Germany uses non-EU country escorts on deportations via commercial flights (Ellermann, 2006: 302), and France used third country escorts at least once in 2003 on a charter deportation to Senegal (Assemblée nationale, 2003: 90). The various forms of delegation of force during deportation flights, be it to other countries or to private escorts, at times provided by airlines, warrant further investigation (Majidi and Schuster, 2019: 100).

next...

17 Whereas interviewed French officials stressed that they would not need the agency to charter aircrafts (French police officials, interviews by the author, February 2020), the agency’s most recent statistics show that the OFII (French Office for Immigration and Integration) did use Frontex’s charter services for some flights (“voluntary” return/departure) in 2020 (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2022). While Frontex’s mandate allows for chartering aircrafts, the agency has not done extensively so to date (i.e. Frontex chartered 13 aircrafts for air deportations in 2019, four of which for readmission operations from Greece to Turkey under the EU-Turkey agreement (Frontex, 2020b: 38)). Not only can Frontex charter aircrafts, but sometimes other states have chartered aircrafts for states that lacked this capacity. For example, when Greece and Italy lacked aircraft in 2016 (Frontex, 2017a: 23-24), other member states chartered aircrafts for their deportation flights, or arrangements were made for Frontex-coordinated deportation flights to make a stopover in Greece or Italy. Of course, these are just examples. As seen before, the agency’s role goes far beyond the deportation flight alone, in particular at the EU’s external borders. In Greece, the agency is, inter alia, involved with the so-called “hotspot approach” and readmission operations under the “EU-Turkey Deal”, for which it charters aircrafts, busses and vessels and deploys escorts. The agency also provides “pre-return support”, such as the deployment of return specialists and the digitalisation of Greece’s return case management system (European Court of Auditors, 2019; Frontex, 2021a: 59-60, 75; Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021). As noted throughout the paper, separating the agency’s “return” from its border operations is difficult in countries at the EU’s external borders.

“We [Frontex] send return experts to various member states to set up such systems [return case management systems] [...]. This is done either at the suggestion [by Frontex] or request by the member state, which of course has to accept it: Belgium, Italy, Greece, what I know” (Frontex official 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

Not only can Frontex charter aircrafts, but sometimes other states have chartered aircrafts for states that lacked this capacity

next...

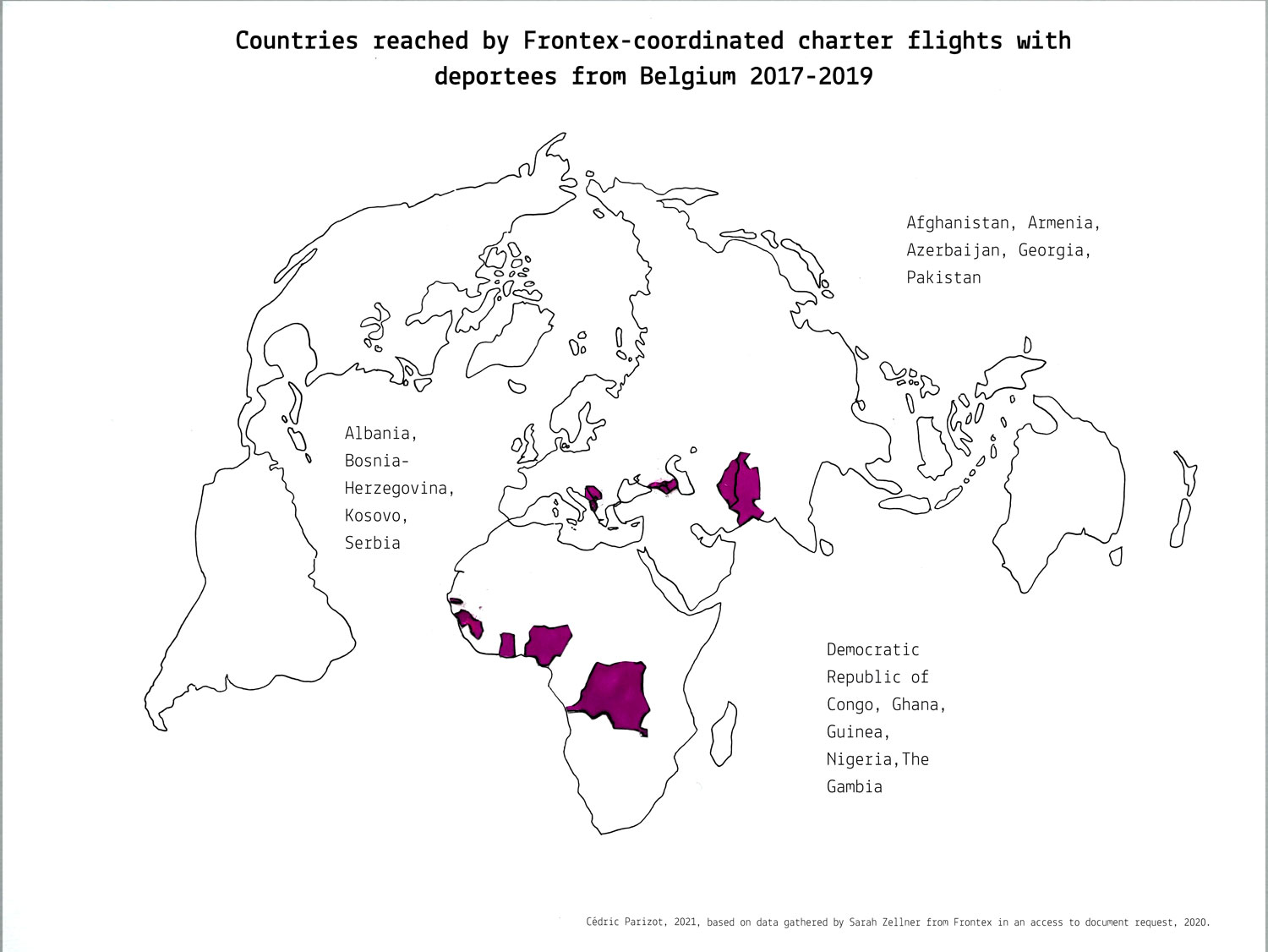

18 Belgium is another instructive example for Frontex’s support for deportations varying from country to country (period examined: 2017-2019). While the country occasionally organised Frontex-coordinated charter flights, more frequently it participated in other countries’ operations, for example in the abovementioned charter flights organised by France. According to a Belgian official, the country does not organise its own charter flights (different from France and Germany, for example), and thus all its charter deportations appear to be Frontex-coordinated (Belgian official of the Ministry of Interior, personal communication, March 2020).

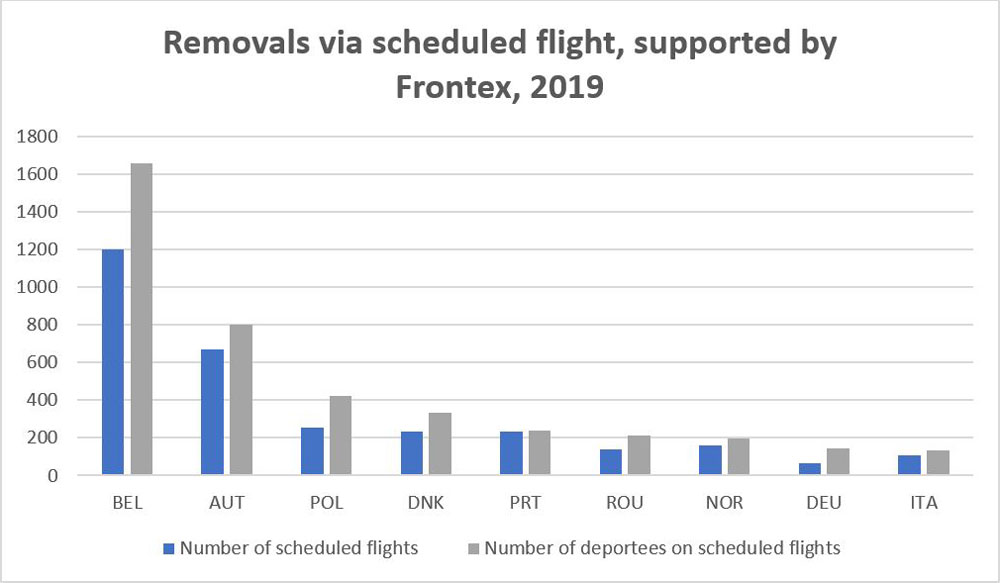

In the examined period, the country also heavily relied on Frontex for deportations via scheduled flights. In 2019, Belgium deported more than 1,500 deportees on commercial flights booked through the Frontex Application for Return, which made it the country making the most use of Frontex’s deportations via commercial flights in 2019 (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020). More recent statistics show that other countries have become the main users of Frontex’s support for scheduled flights, illustrating how the use of the “Frontex offer” by member states is constantly changing (Frontex, 2021d). A Frontex official explaining the rationale behind Frontex-coordinated deportations on scheduled flights notes that:

“[w]e [Frontex] have contracts or agreements with [...] airlines where we can book tickets without names, rebook tickets at short notice [...], so the whole operational requirements for [...] such an individual deportation can be covered better than by a single member state and especially a small member state” (Frontex official 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

next...

Fig. 12: Belgium and Austria relied the most on Frontex support for removals via commercial flight in 2019. Graphic, top 9 countries using Frontex support for commercial flights in 2019, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

19 While not all member states make extensive use of the agency’s “offer”, this section has shown that the agency does increase member states’ air deportation capacities. For each country, several examples of how the country uses the agency have been discussed, but a comprehensive picture is beyond the scope of this paper, even for the countries covered. Whereas Frontex’s funding of removals, through both charter and scheduled flights, seems to be crucial for many states, the agency also enables deportations through material support for removals, ranging from providing an aircraft to video-conferencing identification techniques (German Presidency, n.d.). While National Return Operations are important in explaining the increase in Frontex-coordinated charter deportations from 2016, and in particular the use of the agency by Germany, joint charter flights continue to testify to the unprecedented interconnection between deporting states, as does the proliferation of deportation practices such as Collecting Return Operations.

The agency does increase member states’ air deportation capacities

next...

Fig. 8: “Destinations” of Frontex-coordinated charter flights with deportees from Germany (2017-2019). Note that I am talking about “destinations” of flights, as there may be nationals from different countries on board a flight. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

Fig. 9: France deported people (as organising or participating member state) on Frontex-coordinated charter flights to Albania, Armenia, Egypt, Georgia, Guinea, Kosovo, Nigeria, Pakistan, Ukraine, Serbia and The Gambia (2017-2019). Note that I am talking about “destinations” of flights, as there may be nationals from different countries on board a flight. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

Fig. 10: In 2019, Collecting Return Operations (CROs) were organised by France and Germany to Albania, Georgia, Serbia, Ukraine and Montenegro, whereas several other countries participated with deportees. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

Fig. 11: Belgium deported people (as organising or participating member state) on Frontex-coordinated charter flights to Albania, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Congo DR, Georgia, Ghana, Guinea, Kosovo, Nigeria, Pakistan, Serbia and The Gambia (2017-2019). Note that I am talking about “destinations” of flights, as there may be nationals from different countries on board a flight. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

A “super-agency” within the EU’s deportation infrastructure

20 This section places Frontex within an EU migration control regime and demonstrates how deportation objectives (“effectiveness” and “efficiency”) might make Frontex dependent on certain member states and their take-up of the “Frontex offer” in order to “delive[r] numbers” (RSA and Pro Asyl, 2019: 10). This section serves three purposes. Firstly, to situate the “super-agency” (RSA and Pro Asyl, 2019: 4) within an EU migration control regime and not to minimise the role of member states and the European Commission. Secondly, to show that the agency has imposed few constraints on member states with regard to the form of the charter deportation, the presence of a monitor, as well as the human rights situation in member states, even though Frontex has increasingly applied a “human rights rhetoric” (Slominski and Trauner, 2018: 108). Thirdly, focusing on the limits of deportation policies foregrounds how state actors, or indeed an EU agency or institution, try to overcome these constraints.

Several caveats are important. I do not adhere to the assumption that EU bodies are more “liberal” than member states (for a critical review: Bonjour, Ripoll Servent and Thielemann, 2017). In contrast, the European Commission has continuously pushed for a stronger role of the agency in relation to deportation (Policy advisor in the European Parliament, interview by the author, February 2020). Moreover, this does not mean that the agency has not created standards or constraints, as the agency has produced a plethora of soft law documents such as codes of conduct. Neither do I argue that the agency respects human rights more than member states, nor that member states are more attentive to human rights if they act alone. Lastly, there are constraints that states face when they ask for the agency’s assistance. Street level bureaucrats at the nation-state level complain about the agency, just as Frontex officials complain about member states.

What does “(in)effectiveness” mean for the agency and the actors that ascribe objectives to it? I concur with Sergio Carrera and Jennifer Allsopp (2018) that “in/effectiveness” depends on the actor assessing it and their perspective. As they argue (2018: 79), “[i]n the current EU context, domestic and EU actors mandated or practically engaged in return […] policies and practices appear to primarily view ineffectiveness from the perspective of numbers, control, their own mandates and resources”. At times, objectives for the agency have been articulated in deportation targets, e.g. when the Commission (2019) noted that the agency should support 50,000 removals annually, an objective which is unlikely to be achieved anytime soon. The agency’s Annual Work Programme also formulates targets for deportations via charter and scheduled flights to be supported by the agency (Frontex, 2019a).

Being “effective” means increasing the return rate - the agency is assessed in terms of numbers

According to this logic, being “effective” means increasing the return rate (Stutz and Trauner, 2021). The agency is assessed in terms of numbers (Kalir et al., 2021: 199) and was also in a competitive situation with other EU funds. The EU’s Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) financially covered some of the same tasks as the agency (European Court of Auditors, 2019: 33). The European Court of Auditors noted that “[t]he

two EU funding structures have existed in parallel to finance the same type of forced

return activities” (European Court of Auditors, 2019: 39). This competition might contribute to explaining that the agency has at times imposed limited constraints on the member states, as I will demonstrate in what follows. As an interviewed French police officer puts it,

“if they were to be very obstinate about certain things, they would have less of a track record to present” (French police officer 1, interview by the author, February 2020).

next...

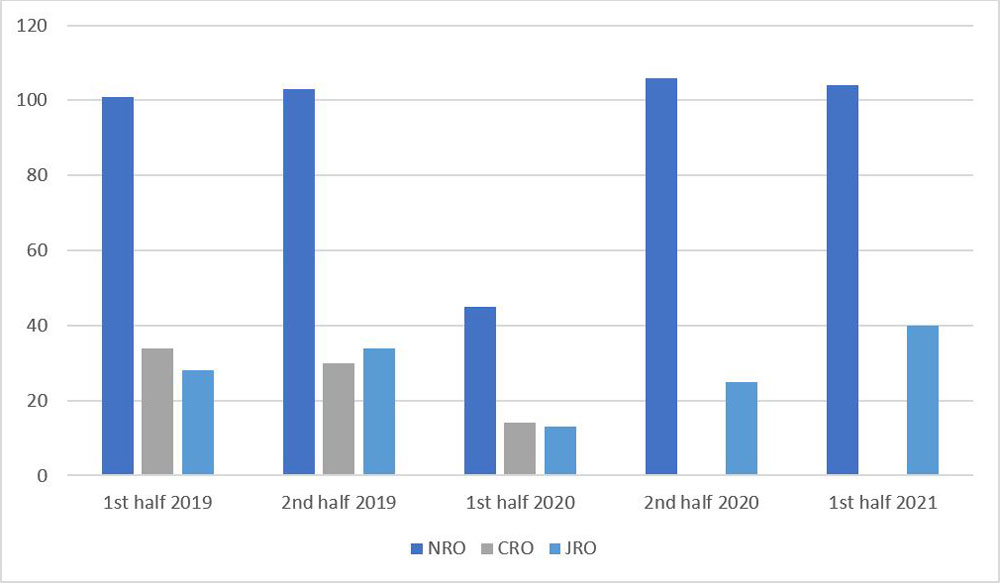

21 One area where the agency is not yet achieving its assigned targets is the share of Joint Return Operations (JROs). The agency’s mandate stipulates that it should prioritise both JROs and charter flights from the “hotspots” when financing return operations (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Art. 50). However, JROs are also more difficult for member states to organise. It is clear from my interviews with French officials that the agency is increasingly emphasising the focus on JROs, and the ADMIGOV reports cite Frontex’s emphasis on JROs as a reason for Denmark’s low take-up of the agency’s support (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021). The agency’s statistics show, however, that it has so far funded every kind of operation, and charter flights involving “only” one country with deportees account for more than 60% of Frontex-funded charter deportations in 2019 (Figure 13). As one French police officer puts it, “[i]f Frontex does not finance the German and Italian charter flights towards Tunisia [National Return Operations, NROs], they have half of their statistics down” (French police officer 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020). While this is exaggerated, if Frontex ceased to finance NROs, their “effective returns” would indeed be much lower.

“Almost two-thirds of the charter flights coordinated by the Agency were national operations […]. [T]he coordinating role of the Agency would certainly benefit from a more coherent EU approach by Member States side within the international cooperation dimension” (Frontex 2020c, 9).

next...

Fig. 13: In 2019, almost two thirds of Frontex-coordinated charter flights were flights with deportees from one deporting country, i.e. National Return Operations (Data for CROs not available for the two most recent periods). Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Frontex, 2020c and 2021d.

22 At the same time, Frontex seems to be pushing states towards organising more Joint Return Operations (JROs) (Frontex, 2020c; Frontex, 2021d), reasoning that JROs “can generally ensure a higher number of returnees in a lower number of flights” (Frontex, 2020c: 18). JROs allow for a last-minute replacement of deportees by another state if one state does not achieve its deportation objective (Frontex, 2020c: 18). While it is not possible to assess how much more “efficient” JROs would actually be, this narrative is propagated by the agency (Frontex, 2021d), conform to “maxims of neoliberal governance (that policies be measurable, responsive, efficient and so forth)” (Reid-Henry, 2013: 203). It remains to be seen whether this will work against Frontex’s continued funding of NROs:

“What would […] bother me the most, there will perhaps also be less systematic financing depending on Frontex’s apprehension about the proposed mission. [...] I had an operation financed [...] last week [...], I had opened up the flight organised by France to other countries, but I had proposed a [single] seat [...], it was a bit vicious on my part, but Frontex nevertheless financed the operation [...], but in the future they might not finance it. [...] So we will try to associate ourselves more with other countries and to associate other countries more with our operations in order to comply even more [...] with Frontex requirements. […] There are many countries that organise operations on their own [...]. Globally, Frontex will at some point say to them, well, we will finance your operations less or not anymore because [...] you do not fit into the concept. [...] So there, [...] I have increased my exchanges with the Germans this year. [...] [T]he flights that are offered until June are open to Belgium and Germany. [...] I have also proposed to Germany to make a stopover in their country to possibly pick them up [...] to avoid future financing problems” (French police officer 1, interview and translation by the author, March 2020).

next...

Fig. 14: Graphic showing how Frontex is assessed against cost effectiveness by the European Court of Auditors, European Court of Auditors, 2019, based on Frontex data.

23 The fact that the agency has so far financed many National Return Operations not only decreased the administrative burden that Joint Return Operations (JROs) entail for member states, but has also enabled an interlinkage between bilateralism and supranationalism. To put it differently, member states can rely on bilateral initiatives with non-EU countries while these deportation flights are being financed by the agency. This also shows certain limits to Frontex’s attempts to mutualise deportations. Olivier Clochard (2010) has noted that the emergence of JROs illustrates states’ difficulties to obtain the authorisations of non-EU countries for deportation charter flights. Indeed, states have “shared” non-EU country contacts through the agency (Ette, 2017: 158). For example, as a Belgian official notes,

“Belgium has privileged contacts with some third countries, and has enabled the organization of JRO’s to those third countries. […] [T]he EU has also negotiated the possibility of the organization of NRO/JRO/CJRO within the readmission agreements or similar agreements with the third countries. The Benelux and Belgium tries to do similar things in their readmission agreements […]. […] So in some cases these negotiations are successful, in other cases not so” (Official in the Belgian Ministry of Interior, communication to the author, March 2020).

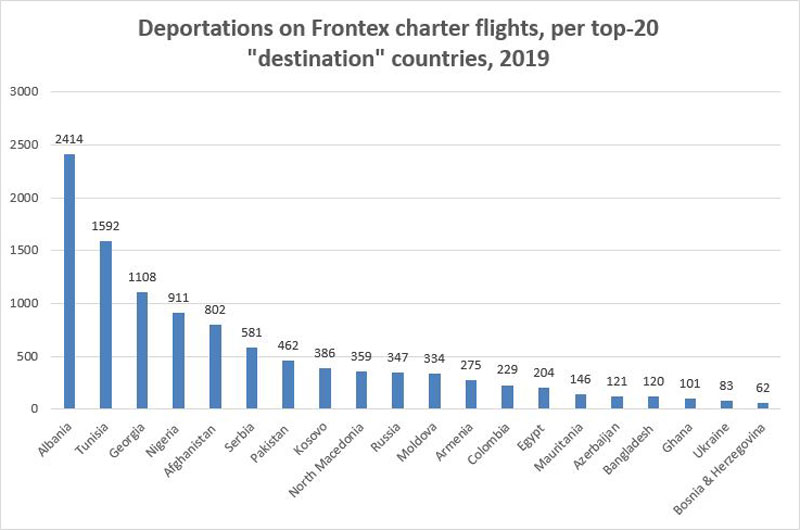

Certain non-EU countries resist forms of deportation

However, some non-EU countries refuse charter flights or, in particular, joint charter flights, which shapes how states make use of the agency’s “offer”. This is an understudied but interesting topic as it highlights how certain non-EU countries resist forms of deportation. While resistance to the EU’s deportation policies should not be overstated, the latter do not go entirely unchallenged. To give an example, Tunisia rejects deportation charter flights from France, the readmission agreement between France and Tunisia stipulating that France should not organise deportations via charter flights (Accord-cadre relatif à la gestion concertée des migrations et au développement solidaire entre le gouvernement de la République française et le gouvernement de la République tunisienne, 2008). In contrast, Germany and Italy have bilateral agreements with Tunisia that allow for such deportation flights (Actionaid, 2019; Die Zeit, 2016). Frontex finances the German and Italian charter flights to Tunisia (NROs). These flights are so frequent that Tunisia was the main non-European “destination” of Frontex charter deportations in 2019 (Frontex, 2020d). Very apt is here Jean-Pierre Cassarino’s (2018, 94) take that “bilateralism has never been so intertwined with supranationalism”. Several interviewed French officials lamented that Tunisia was not accepting charter flights from France, but did so from Italy and Germany.

“[T]he Italians and the Germans managed to negotiate the possibility of organising […] charter flights [to Tunisia] as long as they were alone on board their aircraft. […] We tried to claw at the German operations. But the Germans told us that this was not possible. […] Overall, Frontex is going to subsidise these operations anyways […]. Because in the presentation of its balance sheet […], it allows it to indicate to the European institutions that it has been able to diversify its activity towards different countries” (French police officer 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

“These good bilateral relations are usually not shared by the member states [...] for fear that [the state] will destroy this good relationship for itself [...] and this already applies to member states among themselves, and it applies even a lot more to Frontex. [...] Whereby there are others [...], Belgium has offered [...] the entire relations with their African states [...] to Frontex” (Frontex officer 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

The prism of third country cooperation also contributes to understanding another evolution of the agency’s mandate. The agency’s pilot project on deportations via scheduled flights initially focussed on Algeria and Morocco, two countries that, according to my interviews, refuse deportations via charter flights from most EU countries, including when coordinated by Frontex (Frontex official 1, interview by the author, February 2020). Just as William Walters (2016: 445-446) identified a shift to charter flights as states try to obscure deportations from the public, illustrate their harsh migration policy and reduce the potential for resistance, charter flights appear to have their own limitations, and so do the agency’s Joint Return Operations (Chappart, 2020: 12). Evidently, the EU also continues to exert new forms of pressure on non-EU countries to make them accept readmission as well as specific deportation practices, such as charter flights, for example through the Visa Code revised in 2020. This revision ties visa policy to non-EU countries’ cooperation on readmission, with data for this purpose being collected by the agency (Nicolosi, 2020; cf. the leaked first assessment of non-EU countries’ cooperation: European Commission, 2021).

next...

Deportees per non-EU country for the top-20 “destination countries” of Frontex-coordinated charter flights in 2019. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Frontex, 2020d.

24 As the agency claims, it relies on member states not only for the acceptance of its “offer”, but also for communication of data on deportations. As seen before, the agency’s mandate has broadened over the years towards proactiveness, as the agency can initiate charter flights proactively, instead of “only” taking action when requested by member states. In absolute numbers, this much-touted proactive mandate is not yet well developed. While the initiation of charter deportations by the agency itself has been possible since 2016, the agency has initiated and organised only seven charter flights between the end of 2017 and 2019 (European Commission, 2020). The latest Frontex regulation refers to an “integrated return management platform” (IRMA) connected to the member states’ national IT systems (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Arts 48-50). This platform (IRMA) has been associated with the agency’s more proactive mandate (Jones, Kilpatrick and Gkliati, 2020), as “Member States shall provide operational data on returns necessary for the assessment of return needs by the Agency through the platform” (Regulation 2019/1896 (EU), Art. 50). So far, Frontex has stated that it is not receiving data on “persons ready to be returned” from member states (Frontex, personal communication, June 2020). More generally, the agency complained in leaked documents about the unwillingness of member states to communicate information about their planned operations (Frontex, 2020c). Although it is far too early to assess the impact of these large-scale information systems, of which IRMA is just one example, this is an area that should be closely examined in the future. According to my interviews, the long-term vision seems to be of Frontex having a “closer-to-real picture” of “deportable” people in member states:

“The main argument […] of the Commission […] to have a more centralised system of return managed by Frontex connected with the national return systems […] was indeed to move […] towards more […] charter flights […] that Frontex would proactively propose to member states […]. Because they were saying that member states don’t sufficiently request Frontex for organising these charter flights” (Policy advisor in the European Parliament, interview by the author, February 2020).

Hungary’s participation in Frontex-coordinated charter flights has continued despite the obvious failures in Hungary’s asylum system

Even if the agency did not yet have access to data on “persons ready to be returned” at the time of my research (2020), this does not mean that it did not initiate charter flights. From a human rights perspective, it is significant that almost all charter flights initiated and organised by the agency itself were carried out to Afghanistan and in conjunction with Hungary as the Lead Member State. While the reliance on a Lead Member State shows that the agency does not act in complete isolation from member states, this once again underscores criticism of Frontex. Frontex has often been criticised for supporting deportation charter flights to countries facing conflict, and departing from EU countries with poor human rights records (Gkliati, forthcoming) such as Hungary, whose systematic failures in its asylum and “return” systems are well documented (European Commission, 2018). Hungary has even used Frontex charter flights to coerce Afghan families to return to Serbia, threatening them with deportation on a Frontex-coordinated flight to Afghanistan (UNHCR, 2019). Hungary’s participation in Frontex-coordinated charter flights has continued despite the obvious failures in Hungary’s asylum system, even after the agency had for the first time in its existence stopped its border operations in Hungary in January 2021. Previously, the Court of Justice of the EU had ruled that Hungary’s asylum process was in breach of EU law (Frontex Scrutiny Working Group, 2021).

next...

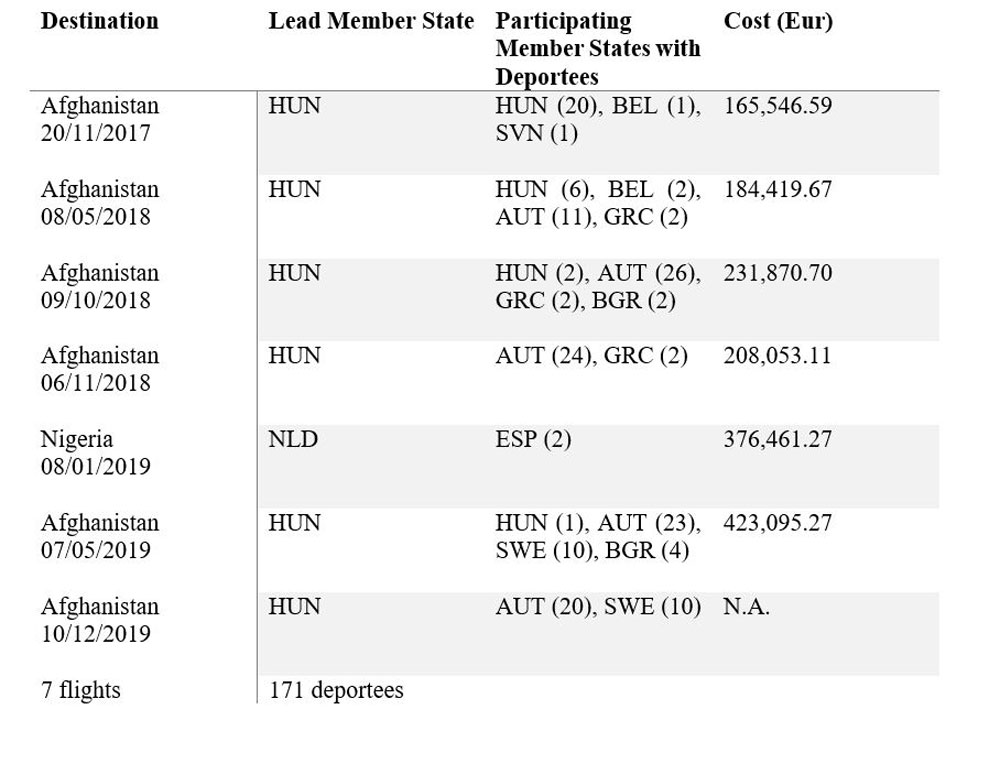

Fig. 16: Deportation flights initiated and organised by Frontex between 2017 and 2019 were mostly in conjunction with Hungary and towards Afghanistan. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020; European Commission, 2020.

25 Finally, I turn to one of the most controversial figures of deportation charter flights – the presence of a monitor, that is bureaucratic visibility institutionalised with the shift to charter flights (Walters, 2016; 2019). EU law can be identified as raising standards in this context, at least when considering only the presence of a monitor (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021: 37). An effective monitoring of forced removal was mandated by Article 8(6) of the Return Directive (Slominski and Trauner, 2014), which requires member states to establish an effective system for monitoring forced removal. Moreover, I argue that Frontex Regulations 2016/1624 and 2019/1896 suggest that every Frontex return operation is monitored (for a similar argument: Gkliati, forthcoming), although the terms of the regulation are ambivalent (Regulation (EU) 2019/1896, Art. 50). The agency’s Fundamental Rights Officer (Frontex 2020c) also notes that each charter deportation should be monitored “in line with the obligation stemming from Article 50(5) of the Regulation” (Frontex, 2020c: 6, see also Frontex, 2021d: 24).

The monitoring of charter deportations is another example of “distributed responsibility”, where the multiplicity of actors serves the different actors to deresponsabilise themselves

The agency’s involvement has indeed increased the number of flights being monitored (data considered: 2016-2019), which represents some sort of “liberal constraint”. Depending on the legislation in force in the Member States, purely national flights without any Frontex support are far less monitored than Frontex flights. I nevertheless argue that this is only a limited constraint for member states. The monitoring of charter deportations is another example of “distributed responsibility” (Reid-Henry, 2013: 206), where the multiplicity of actors serves the different actors to deresponsabilise themselves. One of the main organisers of Frontex-coordinated charter flights – Italy – barely monitored its charter flights in the examined period (2017-2019) (Lemberg-Pedersen and Halpern, 2021: 41). This has not led to Frontex not financing these deportations (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020). Similarly, Germany’s forced return monitoring system has been considered for years as only partially operational by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020). The agency’s Code of Conduct on Return Operations and Return Interventions holds that states “are required to ensure that they have an effective forced return monitoring system” (Frontex, 2018a). Nevertheless, the agency still finances Germany's charter flights. Although almost all Frontex-coordinated charter flights departing from France were monitored in 2019 and one interviewed French police officer noted that an effective return monitoring system was a precondition for the agency’s support, the same officer was still aware of the agency financing flights also without a monitor aboard.

“So overall, […] I sometimes have to set up operations, but as I am not within the 21-day time limit [for demanding a monitor from the Frontex pool], well, I don’t ask. [...] [A]ll countries do more or less the same [...], we talk among European colleagues and the Italians as the Germans, they get funding for their NROs when there is no monitor [...] when they are set up within a limited timeframe. [...] Frontex, the more it finances operations, the more it has a statistical report on their activity, which is interesting to present” (French police officer 1, interview and translaton by the author, February 2020).

“If the member state says that it has […] implemented the [monitoring] [...] and according to the member state this and that is part of the return monitoring and certain parts are not part of it for the member state, such as being on board, then we accept that because we are not responsible for the implementation of the [...] Return Directive” (Frontex official 1, interview and translation by the author, February 2020).

next...

Fig. 17: The share of monitored Frontex-coordinated deportation flights has increased between 2016 and 2019. Graphic, Sarah Zellner, 2021, based on Frontex Annual Reports 2014-2020.

26 Overall, this section should not be read as downplaying the increasing role of the agency in the EU’s air deportations, but has shown the interdependence between member states and the agency, both in practical matters and more broadly, to achieve the removal objectives assigned to the agency. This may be related to member states sometimes successfully circumventing constraints (Woll and Jacquot, 2010). The section has highlighted a polymorphous deportation infrastructure, in which national and European pathways are intertwined.

next...

Conclusion: a symptom of the EU’s deportation syndrome

27 This article examined the use of Frontex by various EU member states and Schengen associated countries, focusing on charter flights coordinated by the agency. It has shown that Frontex has increased the scope of national executive bodies by offering a variety of “services” to member states. As the “Frontex offer” has expanded over the years, it adapts to the deportation infrastructure of different states, while different national and bilateral deportation practices prevail under the “Frontex label”. The expansion of the mandate in 2016 and 2019 contributes to explaining why Frontex-coordinated deportations via charter flight increased significantly in 2016 and 2017. Having mainly examined northern member states, future studies should look more closely at countries at the EU’s external borders to identify differences in the interaction between member states and the agency, as well as forms of pressure on these states (see Borderline Europe, 2021, Amandine Bach, 4:20). In addition, a closer examination of the translation of “policy outputs” into “policy outcomes” would be warranted in the coming years, for example with regard to various large-scale information systems in which Frontex is involved, and more generally to “pre-return assistance”.

As the “Frontex offer” has expanded over the years, it adapts to the deportation infrastructure of different states, while different national and bilateral deportation practices prevail under the “Frontex label”

The agency’s mandate emphasises the importance of mutualisation – whether through Joint Return Operations or the dissemination of all forms of “best practices” in relation to removals, and the agency is pushing member states towards organising more joint deportations. I have shown how such joint “deportation routes and corridors” (Walters, 2017) are shaped, for example the routine of a Collecting Return Operation to Albania organised by France with the participation of deportees from Belgium and Albanian escort officers, all funded by Frontex (period examined: 2017-2019, before the outbreak of the pandemic). However, this article has also shown how the agency’s mandate has evolved towards an approach that aims to support all forms of deportation, and National Return Operations help to explain the increase in the numbers of deportations via charter flight supported by Frontex. Andreas Ette (2018: 232) argues that “the policies addressing the forced removal of irregular migrants […] are characterized by dualist systems combining older national structures with new European ones. Together, these dualist systems have reduced some of the previously existing enforcement constraints, increased the executives’ autonomy, and reduced the political, diplomatic and financial costs of this policy”. National and European structures are not separate, but closely intertwined.

National and European structures are not separate, but closely intertwined

The agency’s mandate extends far beyond charter flights, and the agency expects for the coming years a considerable expansion of removals via scheduled flights (Frontex, 2021c: 124). It is nevertheless important to emphasise that the agency coordinates many (and according to its own documents, most of the EU’s) charter flights to non-EU countries (Frontex, response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020), as charter flights are in themselves a particularly controversial deportation practice. It could be further investigated whether and how the agency has institutionalised this deportation practice, although general secrecy on this topic does not facilitate research.

Since its beginnings, the agency has attracted considerable and justified criticism from NGOs (Léonard, 2010). I have shown that Frontex, when it comes to charter deportations, still relies on at least some member states accepting its “offer” in order to be “effective” and “efficient” in a system defined by deportation targets. Far from downplaying the role of the agency, this serves to expose a polymorphous EU deportation infrastructure in which increasing the rate of returns has been normalised as a political priority. Focusing exclusively on the agency downplays the role of member states and the European Commission. Germany, for example, does not need the agency to organise large deportation charter flights, but willingly uses Frontex funds. Of course, this multiplicity of actors serves both states and the agency when it comes to sharing responsibility for human rights violations that different actors can attribute to each other (see: Borderline Europe, 2021, Omer Shatz at 4:37). The agency is keen to present itself as a technical actor and to emphasise the “exclusive responsibility of Member States” when it comes to return decisions (Frontex, n.d.b). In general, the way the legislation conceives of the agency as a “purely operational” actor makes it difficult to hold it accountable for non-refoulement violations beyond positive obligations (Gkliati, forthcoming).

Overall, this article has discussed the factual and legal expansion of the agency’s mandate, states pursuing all options available to them, the interplay between national, bilateral and European pathways, an agency constantly reinventing its mandate before the legal mandate expansion, and difficulties leading to new inventions in the “art of removal” (Walters, 2016: 439). This bolsters Walter’s argument that “deportation is not merely a policy or a power, but itself a dynamic machine or apparatus that is constantly improvising new ways of removing people, and constantly pushing at the limits of law and ethics in the process” (2019: 166). As such, my research also speaks to Reid-Henry’s work (2013) on Frontex, who – discussing a different set of Frontex activities than I did – pointed rightly to the “oftentimes rather experimental approaches that have been developed in and through Frontex operations at the border” (Reid-Henry, 2013: 201).

The symptom of a polymorphous EU deportation infrastructure that aims to exclude people on the move

Importantly, I have only discussed deportation by air and mostly by charter flight, which is just one part of the EU’s deportation infrastructure. Both Frontex-coordinated deportation by air and Frontex operations at the EU’s sea and land borders (and beyond) are symptomatic of a polymorphous EU deportation infrastructure that aims to exclude people on the move.

next...

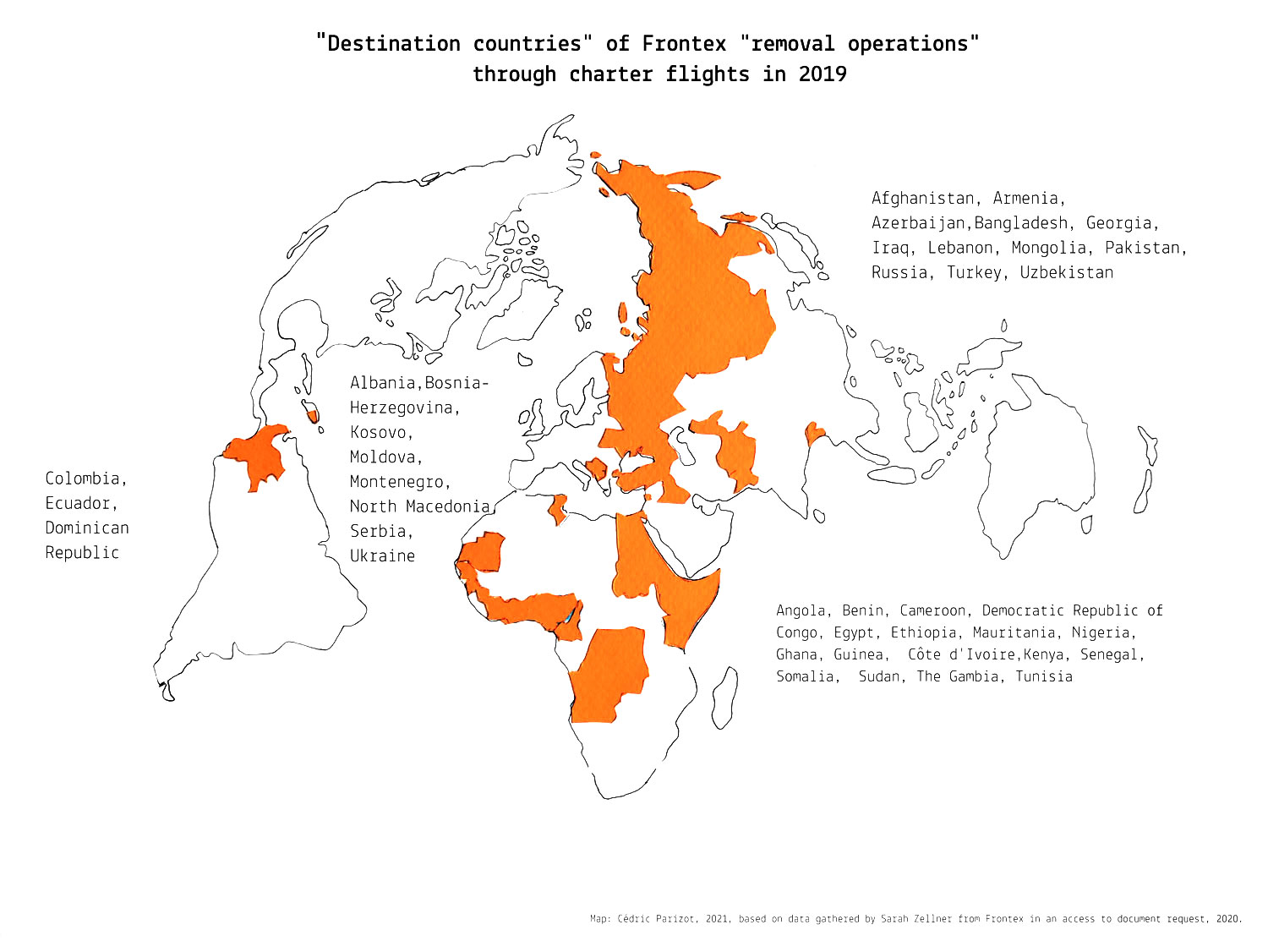

Fig. 18: “Destination countries” of Frontex-supported deportations through charter flights in 2019. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

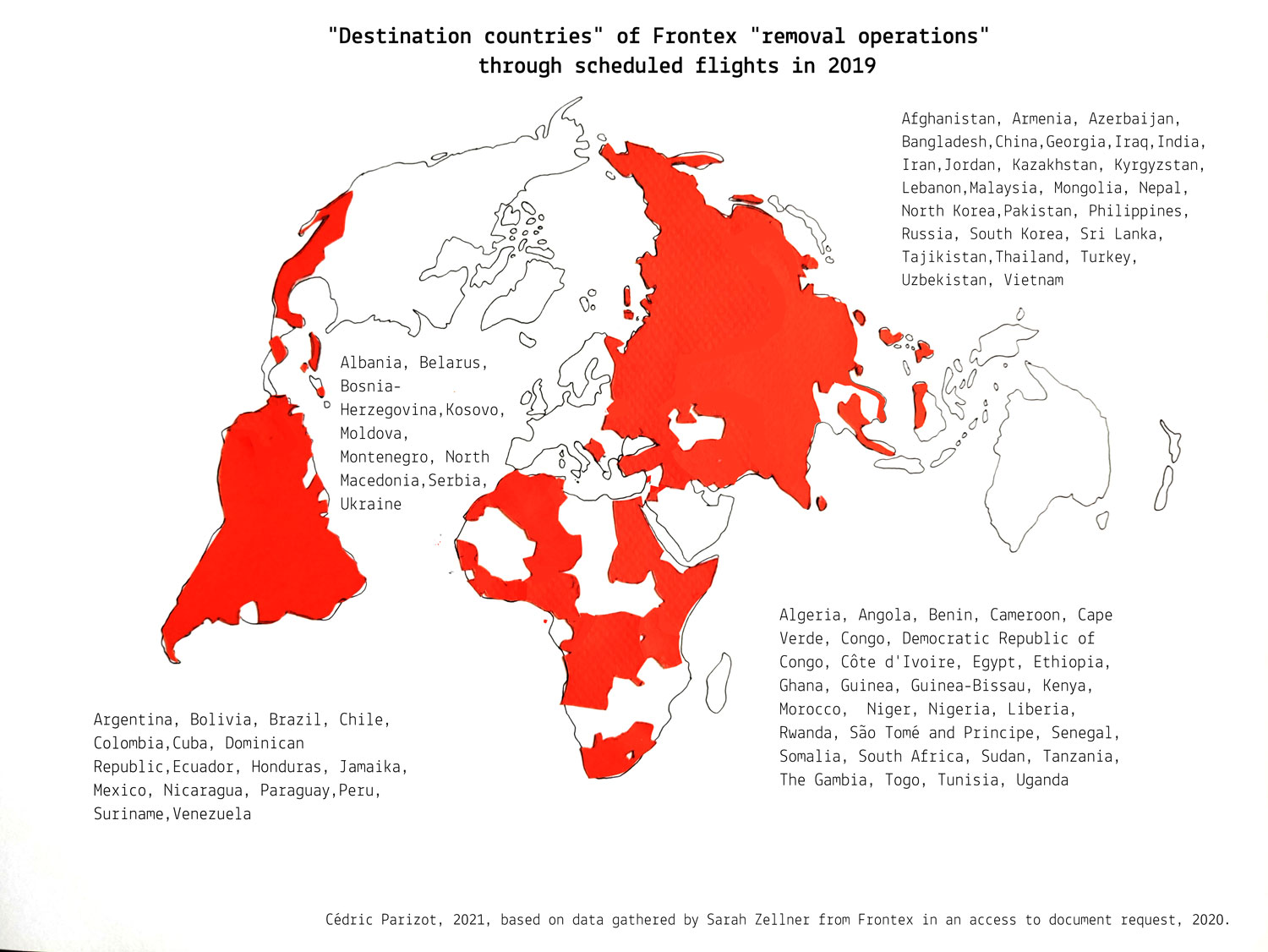

Fig. 19: “Destination countries” of Frontex- supported deportations through scheduled flights in 2019. Graphic, Cédric Parizot, 2021, based on data released by Frontex in response to an access to document request made for this research project, 2020.

References

28

Actionaid, 2019, Willing to go back home or forced to return? The centrality of repatriation in the migration Agenda and the challenges faced by the returnees in The Gambia, https://bit.ly/3dWdoPx (accessed 25 September 2021).

Amnesty International and ECRE, 2010, Briefing on the Commission proposal for a Regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) 2007/2004 establishing a European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States

of the European Union (FRONTEX), https://www.amnesty.eu/news/amnesty-international-and-ecre-briefing-on-commissions-proposal-to-amend/ (accessed 25 September 2021).

Amnesty International, 2021, Illegale Push-Backs von Menschen auf der Flucht, https://www.amnesty.ch/de/laender/europa-zentralasien/griechenland/dok/2021/illegale-push-backs-von-menschen-auf-der-flucht (accessed 25 September 2021).

Assemblée nationale, 2003, Rapport d'information déposé par la délégation de l'assemblée nationale pour l'Union européenne sur la politique européenne d'asile et présenté par M. Thierry Mariani, Député, http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/12/europe/rap-info/i0817.asp (accessed 25 September 2021).

Bonjour, Saskia, Ariadna Ripoll Servent and Eiko Thielemann, 2017, “Beyond Venue Shopping and Liberal Constraint: a New Research Agenda for EU Migration Policies and Politics”, Journal of European Public Policy.

Borderline Europe, 2021, Quo vadis Frontex - Reform, control or abolish?, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5iEpmQrxCU (accessed 19 December 2021).

Bundesregierung, 2019, Drucksache 19/15816, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/158/1915816.pdf (accessed 25 September 2021).

Bundesregierung, 2020, Drucksache 19/21100, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/211/1921100.pdf (accessed 25 September 2021).

Carrera, Sergio and Jennifer Alsopp, 2018, “The irregular immigration policy conundrum. Problematizing ‘effectiveness’ as a frame for EU criminalization and expulsion policies” in Ripoll Servent, Ariadna and Florian Trauner (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs Research, Abingdon, Oxon and New York, Routledge: 70–82.

Carrera, Sergio, Steven Blockmans, Jean-Pierre Cassarino, Daniel Gros and Elspeth Guild, 2017, The European Border and Coast Guard. Addressing migration and asylum challenges in the Mediterranean?, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS Task Force Report), https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/european-border-and-coast-guard-addressing-migration-and-asylum-challenges/ (accessed 25 September 2021).

Cassarino, Jean-Pierre, 2018, “Informalizing EU Readmission Policy” in Ripoll Servent, Ariadna and Florian Trauner (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Justice and Home Affairs Research, Abingdon, Oxon and New York, Routledge: 83–98.