antiAtlas #2, 2021

On Countries and Hotels: Disassembling Narratives of Time and Place

Beatrice Bottomley

This article is related to the issue #2 of antiAtlas Journal, Fiction and Border: read the introduction. This second issue of the antiAtlas Journal focuses on the relationship between fiction and the border. The goal is to show how fiction, conceived as a strategy, cuts across and shapes very different approaches; whether they are the result of artistic experiments or of scientific research, they all tackle borders by being control mechanisms, political and economic operators and systems of representing space all at once.

On Countries and Hotels (2007) is a collection of short stories by the Palestinian writer Raji Bathish. The stories take place in hotel rooms that are marked by the strong presence of media, or means of communication, allowing for a disassembling of linear time and place. To what extent does this enable the text to produce a space of movement? And what is the potential of such a space? The iconography of this article was co-produced with Thierry Fournier, artistic director of antiAtlas Journal. It draws on, and respond to, the multiple times and places, both public and private, that unfold in the worlds of the text and its translation. Beatrice Bottomley is a doctoral candidate at the Warburg Institute, University of London, supported by a studentship from the London Arts & Humanities Partnership. Her research interrogates the relationship between language and philosophy. Keywords: contemporary palestinian literature, raji bathish, space, time, rhizome, heterotopy, hotel rooms, media.

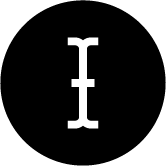

'Mariam narrates, one afternoon in Ramallah', Still from 'On Countries and Hotels, taken by the author, Ramallah, 2017.

To quote this article : Bottomley, Beatrice, "On Countries and Hotels: Disassembling Narratives of Time and Place" published on October, 8th, 2021, antiAtlas #2 | 2021, online, URL : www.antiatlas.net/02-on-countries-and-hotels, last consultation on Date

1 Over the last few years, the idea of annexing the occupied West Bank has travelled from the fringes of the Israeli far-right to the heart of the mainstream, finding its way into the coalition agreement signed between the political parties Likud and Blue and White on 20th April 2020. Even within the context of a global pandemic, the new Israeli government’s announcement that they planned to bring legislation to annex large parts of the West Bank to the Knesset, starting on 1st July 2020, did not go unnoticed. Protests erupted in the occupied Palestinian territories, Israel and across the world. Annexation is the formalization of occupation, dispossession and violence. To a certain extent, these protests felt familiar. They served as a reminder that annexation is the formalization of occupation, dispossession and violence that has taken place over decades. With this, I found myself returning to ‘An al-bilād wa-l-fanādiq (On Countries and Hotels), a collection of short stories written by Raji Bathish and published as part of the collection Ghurfa fī Tal Abīb (A Room in Tel Aviv) in 2007. The stories navigate the intimate and the political, the absurd and the dramatic, illustrating the complex nature of both everyday life in a colonial context and anti-colonial struggles centred on narratives of statehood. next...

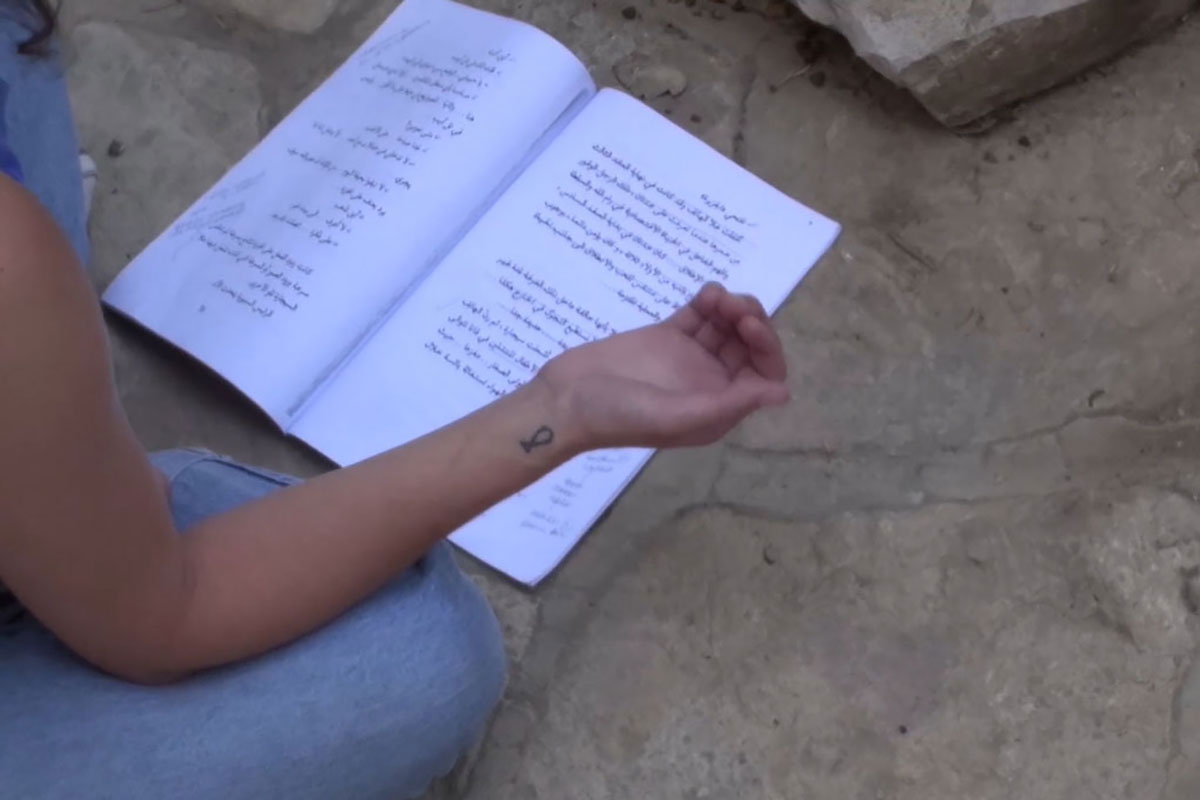

Left: Title Page of 'A Room in Tel Aviv', Raji Bathish, 2007.

2 Raji Bathish was born in 1970 in Nazareth, Israel, where he lives now. His work is written, for the most part, in Modern Standard Arabic, although he also draws on Palestinian dialect and Modern Hebrew. Raji experiments with form; his writing ranges from short stories to novels and plays, from poetry to posts on social media. We could understand him as part of a nineties generation of Palestinian writers, who, following the political deception of the Oslo Accords in 1993-1994, in Bathish’s words, came with themes mired in subjectivity, the personal, the macabre, and the ambiguous thus breaking with the established imagery and discourses developed by previous generations of Palestinian writers. Palestinian writers came with themes mired in subjectivity, the personal, the macabre, and the ambiguous.On Countries and Hotels is made up of seven stories. Each story has an independent narrative and characters; however, they share some common features. Each story takes place in a hotel. All of the protagonists are (explicitly or implicitly) Palestinian and live in, or are from, cities that are now part of the state of Israel, including Nazareth, Tel Aviv and Haifa. The stories also share the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon as their setting. In the story Haytham, the protagonist sits alone in his hotel room in Utah, reflecting on his unfulfilled sexual desire and the bleak years to follow as he undertakes his PhD in America. In Ka'anna-nā fī dawla ukhrā (As if we were in another state), Jad travels to Jerusalem in order to commit suicide, but does not succeed, instead losing himself in a game of football. Salsabil, in Ghurfa fī ‘amman (A Room in Amman), watches television, fantasizes about an affair with the porter and regrets her stifling family life. In 'Ulā (Olaa), the protagonist waits in a hotel room in Ramallah for her older lover and watches a massacre unfold. Hadeel, in Ḥamīmiyya (Intimacy), meets her Israeli lover in a hotel room in Tel Aviv. Politics disrupts the usual anonymity of their encounters. In Kulūd (Claude), the protagonist, in a hotel in Paris, suffers a crisis about ageing and telephones her sisters in Beirut and Haifa. Khalil, in Ḥaflat al-raġwa… fī wasṭ Madrīd, (A Foam Party, In the Centre of Madrid), stops in Madrid on his return from Venezuela to Haifa and checks his long-ignored emails, finally abandoning the idea of replying to attend a foam party instead. The setting of the stories in hotel rooms and the strong presence of media, or means of communication, allow for a disassembling of linear time and place. To what extent does this enable the text to produce a space of movement? And what is the potential of such a space? next...

Right: Photos, finding moments of humanity in a hotel room. Stills from 'On Countries and Hotels', taken by the author, Ramallah, 2017.

3 Chronological time is associated with a linear series of events or dates and has come to be considered a key element of narrative; the importance of which extends beyond literature into how we think about the writing of history and nationhood. If we follow the conventional practice of reading (that is to say, reading each story in linear order from right-to-left in Arabic), we notice immediately that the stories of On Countries and Hotels are not ordered chronologically. The events of each story do not follow the events of the previous story in the collection. Indeed, the events of each story seem to take place before, or long after, the events of the previous stories, or do not take place at a specific point in time at all. Thus the stories seem to be neither ordered nor qualified by chronological time. The reader may infer that collection is set within the period of the 2006 was between Israel and Lebanon, but each story is not fixed at a specific point in that period. For example, in A Room in Amman, the author indicates that the story takes place during an unspecified September: كان الجو باردا ... برد غريب بمثل هذه الساعة من العصر الأيلولي [Baṭḥīsh,R. (2007) Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p25.] (The weather was cold, strangely cold for such an hour on a September evening.) It is for the reader to deduce, if they wish, that the action takes place in September 2006 from the context of the war described by the other stories. Similarly, in Claude, the date of the main action of the story is never made explicit. However, we understand that the story takes place in the context of a war with Israel from the dialogue between the main character and her sisters: - نهلا؟ ... ما هذا الصوت؟ - قصف إسرائيلي... يظهر أنه بدأ يزحف من الضاحية شمالا... [Ibid., p41] (“Nahla? What’s that sound?” “An Israeli bombardment. It seems that they’re beginning to advance from Dahieh northwards.”). It is only in leaning on the context of the other stories that we are able to suggest that the action takes place during the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon, although it is still not clear on which specific day the story takes place during the war. next...

4 We begin to lose the sense of time passing through a linear sequence of events; instead time seems to fold out (or rather “pour out”, as we see in As If We Were in Another State from events that unfold from inside other stories, such as the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon. However, sometimes the descriptions, actions or dialogues seem incomplete, leaving us with the sensation that the story is a fragment that unfolds from an event, or events, outside of the stories. For example, let us consider the first story Haytham. We follow the protagonist, Hani, in the taxi, in his hotel room, lying on the bed, watching TV and so on; little suspense is provided up until the moment he finds a note from an unknown mother, who reveals that she has met a new lover and is leaving the family. She sends kisses to her children Nancy, Linda and… Haytham. The protagonist is troubled by the fact that one of the children is called Haytham and the story finishes with the line: هيثم؟؟ قالها هاني بصوت مرتفع.... وهرول الى الحمام باحثا.... [Ibid.,p13] (Haytham? Hani said with a raised voice, and hurried to the bathroom searching.) A sensation that the story is a fragment The source of his trouble is never revealed, neither do we find out what he rushed into the bathroom looking for. The sentence is incomplete, the verb lacks an object, as if to be completed in an event outside of the story. In Olaa, for example, the protagonist Olaa is waiting for her lover Adnan in a hotel room in Ramallah when she receives an unexpected call from a character called Raghad: - أنا في رام الله... ولن تصدقي مع من! - نعم؟ - مع عدنان... إنه ما زال يحبني يا علا... شكرا... شكرا على المساعدة. هو لا يسمعنا الآن لقد ذهب الى الحمام.. - رغد... يجب آن أذهب... يبحثون عني... [Ibid.,p31] (“I’m in Ramallah. You won’t guess who with!” “Who?” “With Adnan, he still loves me Olaa. Thank you, thank you for your help. He can’t hear us now. He went to the bathroom.” “Raghad… I have to go. I’m wanted.”) It is never made explicit who Raghad is, but we understand that she is a friend of Olaa’s and is also intimate with Adnan. The dialogue does not follow on logically from the action of the story, rather it seems to unfold from events, of which we are unaware, that took place between the two characters outside of the story. The apparent linear series of events in the story is interrupted by the unfolding of an event outside of the story (but inside the world of the text). This phone call not only disturbs the linear progression of the story, creating an element of surprise, but also disrupts the omnipresence of the narrator, making room for polyphony. next...

Left: Screenshot, making the stills into footnotes. The process of transmediation, or translation into film, opened up reflection on the presence of different voices and the movement between times and places.

5 As we saw above, the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon forms a common event from which the stories unfold. The war really took place outside of the text and remains in living memory for many, both in the region and beyond. When researching the period, I found myself confronted by highly conflicting accounts. Indeed, the impossibility of constructing a single “true” chronology of the war is highlighted in Intimacy, when Hadeel discusses the beginning of the conflict with her lover Ephraim: - إطلاق الكاتيوشا جاء ردا على إعلان الحرب... والرد العنيف غير المتكافئ.. - غير صحيح... الصواريخ أطلقت فبل ذلك. - أنت لا تعرف شيئا... لقد غسلت أكاذيب التلفزيون الإسرائيلي دماغك... الصواريخ جاءت بعد... - ... قبل [Baṭḥīsh,R. (2007) Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p37.] (“The rockets were launched in response to the declaration of war and the excessively violent reaction.” “It’s not true. The rockets were launched before that.” “You don’t know anything. You’ve been brainwashed by the lies of Israeli television. The rockets came after.” “Before.”) We come to understand it as a rupture from which time unfolds. This impossibility means that rather than seeing the war as a linear series of events, in which we can locate the stories, we come to understand it as a rupture from which time unfolds. For example, the first story Haytham unfolds from the beginning of the war, even though the action of the story itself takes places months afterwards: والطريف أن قبوله النهائي للمنحة جاء في يوم الارباء ١٢ تموز أي في يوم اندلاع الحرب.... ومن يومها لم يذهب الى تل أبيب بل ظل في الناصرة يتابع الحرب وينتظر صفارات الإنذار ويتهيأ للسفر، حتى إنه لم يدقق تماما بتفاصيل المنحة جغرافيا... المهم أنها عبر البحار... في أمريكا... وانتهت الحرب وجاء موعد السفر بعدها بعشرة أيام... هكذا... الحرب... هذا الصيف المجنون... وكأنه تكاثف خصيصا كي يذكّر هاني مرة واحدة ولأبد بالفرق بين المكان والاماكن... [Ibid., p10] (Curiously, his final acceptance to the scholarship came on Wednesday 12th July, in other words, the day war broke out. From that day he did not go to Tel Aviv but remained in Nazareth, following the war, waiting for the warning sirens and getting ready to travel, although he had not carefully examined the details of the location of the scholarship. The important thing was that it was across the seas - in America. The war finished and the appointed departure date came ten days afterwards. And so it continued, the war… That crazy summer... It was as if it had become especially condensed in order to remind Hani, once and for all, of the difference between place and places.) In A Foam Party, in the Centre of Madrid, the first official day of the war also provides a rupturing event which defines time. The story revolves around Khalil’s need, or rather obligation, to check his emails after a two-month voyage in Venezuela, far from Haifa and the responsibilities that await him there: لم يعرف خليل كيف يبدأ؟ من الآخر أي ٧/٨/٢٠٠٦ أم من الأول ٥/٦/٢٠٠٦... ولكن من الطبيعي والمنطقي أن كل ما أرسل قبل ١٢/٧/٢٠٠٦ أي يوم اندلاع الحرب... لا قيمة حقيقية له... أو أن مضامينه غير نافذة بالقوة ذاتها التي كتبت فيها... ما فبل ١٢/٧ وما بعدها... بالتأكيد تغير كل شيء... [Ibid., p47] (Khalil did not know where to begin. From the last emails, that is those dating from 7th August 2006, or from the first, dating from 5th June 2006? It was natural that everything sent before 12th July 2006, that is the day war broke out, would be of no real importance or relevance. What is before 12th July, what is after. It certainly changed everything.) next...

Above: Still from ‘A Mission in Tel Aviv’ (1992). The stories are littered with references to Egyptian comedies and Lebanese chat shows. These references create a shared cultural framwork from which Bathish draws much imgary, melodramatic language and situations (including Claude's breakdown)

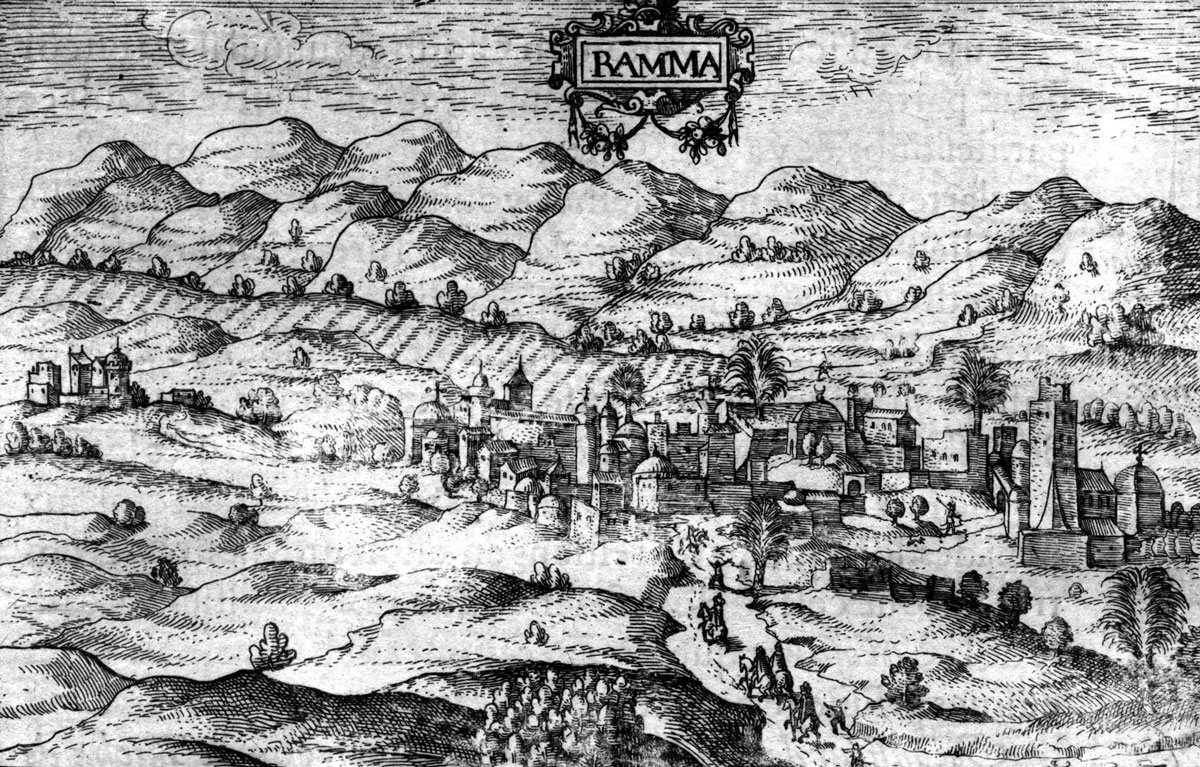

Below: Ramallah, drawing by Henri de Beauveau, 'Relation iournaliere du voyage du levant faict & descrit par haut et puissant Seigneur Henry de Beauvau', Nancy: Jacob Garnich, 1615.

6 However, as we saw above, the war is not the only event from which the stories unfold; other events, fictional and real, outside and inside of the stories define dimensions of the time. Time even comes to be defined internally by protagonists. For example, in Claude, although we are aware that the story takes place during a war between Israel and Lebanon from details in the dialogue, we are more conscious of a time defined through the ageing of the body. The story begins: لم أعد جميلة..... جلست كلود أمام المرآة المترامية الأطراف وأخذت تتأمل بهلع التجاعيد التي ازدادت بفداحة ذلك اليوم... [Ibid.,p39] (I am no longer beautiful. Claude sat in front of the expansive mirror and began to consider with dismay the wrinkles, which had increased overwhelmingly that day.) It is the protagonist’s body, and experience of ageing, that defines time in the story, we receive little description of events, such as the war, which are external to the protagonist. In the example above, the first sentence uses the first person singular, introducing another voice into the text and placing emphasis on the interiority of the protagonist. Here again, another voice breaks into the narration, creating polyphony and disrupting the possibility of a singular, omnipresent narrator, so often associated with the traditional narrative form in European literature. In As If We Were in Another State, we are aware that the story is set on 12th July 2006 and glean contextual details from dialogue between characters. However, it is never explicitly mentioned that July 12th is the first day of the war; the significance of the date is indicated in other stories. Emphasis is placed on a flow of time defined by the cycle of night and day and by the protagonist’s body, rather than by a sequence of defined events: لقد فقد جاد معنى الأشياء في الأطراف البعيدة و اصبح مركز كيونته مراكز متعددة غير مهمة.... دون وقع حقيقي يظلل الأشياء ويقودها نحو نقاط ترقّب مثيرة... حتى غدا داخله يتآكل ببطء واستمرار طوال الليل والنهار... [Ibid., p15] (Jad had lost the meaning of things in the far fringes. The centre of his being had become many centres without importance. Without anything really happening, things continued, and he guided them towards exciting points of anticipation. Until he began to corrode on the inside, slowly and continuously throughout the night and day.) The centre of his being had become many centres without importance. Indeed, from the beginning of the story we already have a sense of being beyond the sequence of events that make up a chronological time: عاد جاد الى القدس... كي ينتحر فيها... وقد جاء اختياره سريعا دون تردد يذكر.... لأنه طالما اعتبرها مدينة تفوق عظمة صمتها في كل ما يحىطها من أمور عابرة... [Ibid.,p15] (Jad returned to Jerusalem, in order to commit suicide. He had made his choice quickly, without the least hesitation. He had always thought that the greatness of the silence of the city surpassed all the transitory affairs that surrounded it.) next...

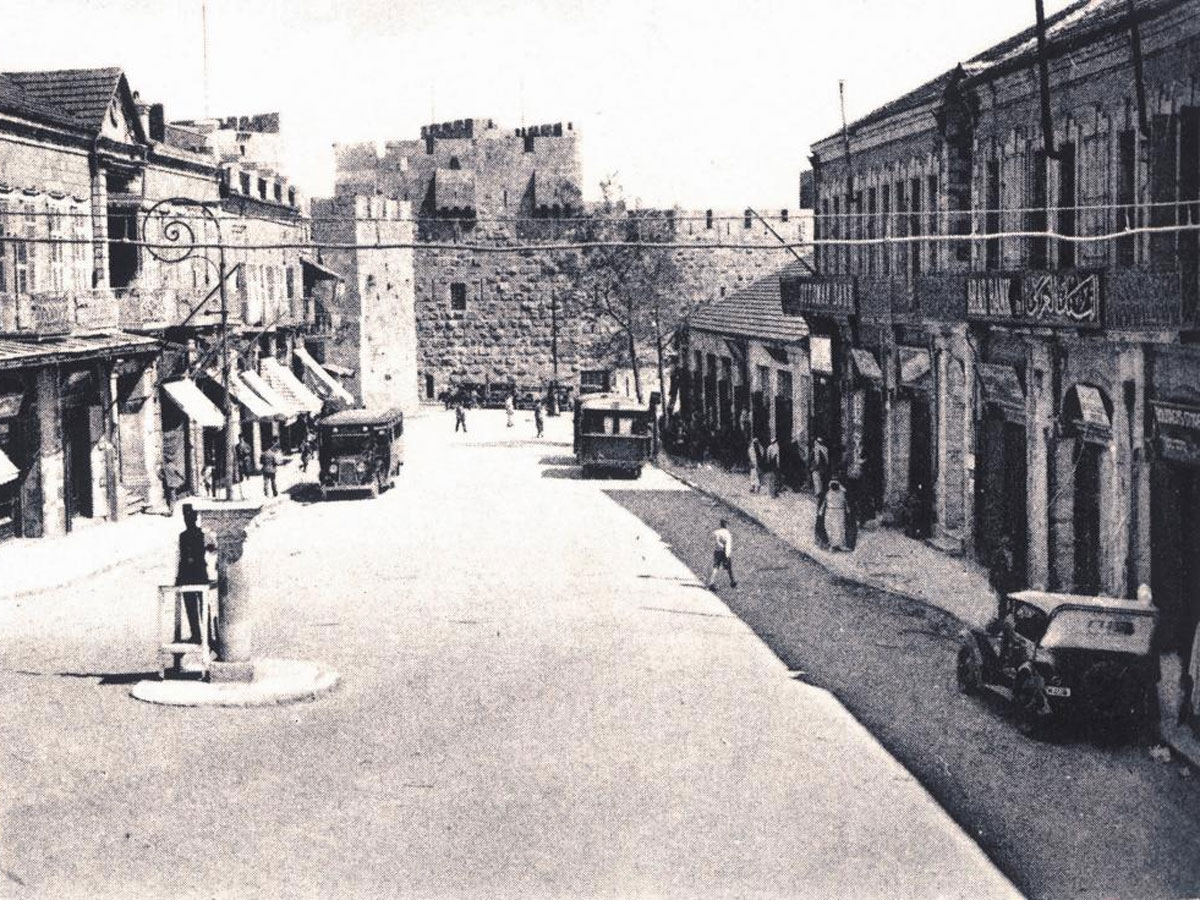

Jerusalem, hotel Mamilla, beginning of the XXth century

7 The significance of the events that mark chronological time seems to fall away. A theme that we find again in A Room in Amman. As we saw above, no exact date is given for the main action of the story, we are only aware that it takes place on an evening in September. The seventh form of the root d-th-r, “to be obliterated... to fall into oblivion”, is repeated twice to describe time: وبانها باتت مربوطة بحبل سميك واحد مع كل ما تسعى للفرار منه... أمها المتسلطة... ابيها الأعمى... (...) هذا الزمن المندثر... [Baṭḥīsh,R. (2007) Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p24.] (She had become attached by a single, thick cord to everything she desired to flee. Her oppressive mother, her blind father (…) This time fallen into oblivion.) and in the final sentence of the story: وهناك كان ينتظرها يزن، (...) وابتسامة ساحرة تطلق احتمالات تتجدد.. في زمن يندثر... [Ibid.,p25] (… and there was Yazan waiting for her (…) an enchanting smile exuded promises of renewal, in a time that falls into oblivion.) Chronological time has not completely disappeared; indeed, it is evoked in the use of dates. However, as I mentioned above, the author seems to encourage the reader to step outside of it, in Olaa: استملت علا مفتاح الغرفة في الفندق المحذوف خارج الزمن في رام الله، كأنه لا يوجد في وسط بؤرة اهتمام عالمي... [Ibid.,p27] (Olaa picked up the key to her hotel room, cast away outside of time in Ramallah, as if it was not at the centre of the world’s attention.) And again in A Foam Party, in the Centre of Madrid: ولكن ها هو يجلس في هذه الشقة الفندقية الجديدة في وسط مدريد ... مرهقا من عبثية السكينة... يشعر كما لو كان خارج المكان والوقت وكأنه يزحف داخل ذلك النفق بعكس الاتجاه الوحيد... هو والانترنت وحساب بريده الالكتروني فاغر ألفيه... [Ibid.,p47] (But here he was sitting in this new apartment hotel in the middle of Madrid, overwhelmed by the absurdity of the tranquillity. He felt as if he was outside of space and time, crawling the wrong way along a one-way tunnel. He, the internet and his email account mouth gaping.) He felt as if he was outside of space and time We find ourselves in a time outside of chronological time. Taking our cue from Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope, we could consider this time outside of time, or outside of chronological time, to find form in the hotel room, a setting that calls into question our understanding of space and place. next...

Right: The city of Amman in 1970

Below: Map of Madrid (detail), 1902

8 If we draw on de Certeau’s comparison of space and place in Récits d’Espace (Tales of Space) from L'Invention du quotidien, 1 : I'Art de faire (The Invention of the Everyday, 1: Arts of Doing), we can understand place as a location of positions and material elements, which is invested with collective meaning by people. Space, however, is more abstract and could be considered as the product or effect of actions or practices. When describing the hotel in Haytham, the narrator locates it rather vaguely in Utah, surrounding it with fields of corn that could be found anywhere: اشتقت لزافين... هذا ما ردده هاني الذي تلقبه امه بهنوش لنفسه وهو في طريقة بسيارة الأجرة التي اقلته من المطار شبه المهجور في أطراف ولاية يوتا الى الفندق الذي لا تحيط به سوى حقول الذرة... [Baṭḥīsh,R. (2007) Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p9.] (I missed Zaven. This is what Hani, nicknamed Hanoush by his mother, said to himself in the taxi from the seemingly deserted airport in the fringes of Utah to the hotel, which was surrounded by nothing but fields of corn.) Indeed, the hotel room and its surroundings are empty and silent: كانت الغرفة مرتبة جدا ومحيطها صامت جدا وكأن اشباحا كانوا قد جهزوها وفرّوا مللا... [Ibid., p12] (The room was very tidy and its surroundings very silent, as if ghosts had prepared it and fled, out of boredom.) The hotel room has a geographical location, Utah, but has no specific material elements that could be invested in meaning, nor any humans to take part in the process of investment, negating its ability to constitute a place in itself. Likewise, the hotel in A Foam Party, in the Centre of Madrid, has never been inhabited by people before: كانت الشقة الفندقية التي استأجرها في مدريد جديدة... جديدة جدا... كل شيء يلمع الى درجة الإزعاج وكأن لا روح زارت المكان من قبل... الأثاث معظمه أزرق غامق مع القليل من الأبيض... شقة ينقصها الدفء الذي يميز التصاميم الأوروبية السخية بالألوان... كما تنقصها رائحة بشر... تلك الرائحة التي تترك آثارها في المكان حتى وإن تم تنظيفه بأكثر وسائل التعقيم تعقيدا... [Ibid., p34] (The apartment-hotel that he had rented in Madrid was new, very new. Everything inside it gleamed to a disturbing degree. As if not a soul had visited the place before. Most of the furniture was dark green with a little white. An apartment lacking the warmth of European design, which is rich in colour, as it was lacking the odour of humans. That odour which leaves traces in a place, even if one uses the most elaborate sterilising methods). As if not a soul had visited the place before. In the example above, the narrator describes the material features of the room, but they remain rather vague and hard to picture. In most of the stories the author gives little, or no, description of the rooms; they remain without material elements that could be invested in memory or meaning, as the narrator points out in Intimacy: دخلت هديل الى الغرفة بالتفاصيل التي لا يمكن تذكرها بعد بدقائق... [Ibid., p35] (Hadeel entered the room, the features of which she was not able to remember minutes afterwards.) next...

Cover of 'A Room in Tel Aviv', Raji Bathish, 2007.

A street in Salt Lake City, Utah, Google Sreet view, 2021

A hotel room in Madrid, 2021

9 Following de Certeau’s ideas on place, the hotels in 'On Countries and Hotels', seem to be quasi-places; they are composed of a location of elements, but the elements remain vague and without significance. The hotels are, however, associated with spaces, including spaces of deviancy. Even the cover of the book plays on this association; illustrating a sort of ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign with a broken martini glass hanging on a hotel room door. A recurring motif in the stories is illicit or adulterous affairs. In Intimacy, Hadeel meets with her lover Ephraim once a month in a hotel in Tel Aviv: دخلت هديل الى الغرفة بالتفاصيل التي لا يمكن تذكرها بعد بدقائق... [Ibid., p33] (The hotel was one of many spread along Ben Yehuda Street, which caresses the coast in the centre of Tel Aviv. The hotels rent their rooms for a minimum of three hours for 25 dollars, thus embracing tens of projects of fiery, instant passion, watched over by that great city.) In these spaces of deviancy, the ordering of society is called into question. In these spaces of deviancy, the ordering of society is called into question. For example, again in Intimacy, the trope of the Palestinian character as other, subject to the European gaze, is turned on its head: أهم ما كان يميّز أفراهيم الملقب ب«إيقي» أنه كان يمنح الحب بانسياب وكمال لا توحي به ملامحه الشمال أوروبية الحادة... وأهم ما كان يميز هديل أنها كانت مولعة بذلك التباين... [Ibid., p34] (The most important thing that characterized Ephraim, nicknamed “Ephi”, was that he consecrated to love a flow and consummation that was in contrast with his hard, northern European features. And the most important thing that characterised Hadeel was that she was crazy about this contrast.) Similarly in A Room in Amman, the protagonist, Salsabil, practices the hotel room as a space of deviancy; she uses a literary meeting in Amman as a pretext for celebrating her birthday with her younger lover. In this way she seeks respite from her oppressive home environment. In the hotel, she performs the roles of poet and lover, rather than those of mother, daughter or sister, unsettling the position that she normally occupies in society. She even goes further to fantasize about sleeping with the porter of the hotel: كانت فكرة مضاجعة حامل الحقائب فور الوصول لذيذة... لذيذة جدا بمثابة فانتازيا طالما تبادلت فكرتها الصديقات في جلسات سمرهن على نسق «سيكس آند ذا سيتي» ... فكرة لذيذة ومخيفة أيضا أو بالأصح مريبة... فقد تكون الغرفة مراقبة من المخابرات بححه أن ساكنتها ممن يطلق عليهم «عرب الثمانية والأربعين» حاملو الجوازات الإسرائيلية أو بوليس الآدب كما يحدث دائما في الأفلام المصرية، فتحول التجربة الجسدية المثيرة إلى كابوس لا أول له ولا آخر، وإضافة الى الفضيحة والصحف والسجون وزنزانات التعذيب بالماء والأفاعي وبراز الضباط... [Ibid., p22] (The idea of sleeping with the porter just after arriving was alluring. Highly alluring as a fantasy, like those she exchanged with friends during one of their gossip sessions à la “Sex and the City”. An idea that was alluring as it was alarming, or at the best troubling. The room could be under surveillance by the secret police, under the pretence that its inhabitant was one of what they called “the Arabs of forty-eight” who carry Israeli identity cards, or by the Vice Squad, as it always happens in Egyptian films. Thus the exciting carnal experience would turn into a nightmare without beginning or end. This in addition to the scandal, newspapers, prisons and torture chambers complete with water, snakes and the faeces of officers.) However, Salsabil does not bring her fantasy to fruition. Her, almost burlesque, projection of the repercussions of this act in the spaces outside the hotel provides a reflection on the norms of gender and sexuality that both order society and also, according to Bathish, inhibit its evolution. Indeed, it is from the hotel room that the author seems able to reflect on the surrounding spaces and the societies that produce them. Bathish calls into question the narratives of nation, gender and sexuality that both order, and are ordered by, society. To a certain extent, this brings to mind the concept of heterotopy, as elaborated by Foucault: « Il y a également, et ceci probablement dans toute culture, dans toute civilisation, des lieux réels, des lieux effectifs, des lieux qui sont dessinés dans l’institution même de la société, et qui sont des sortes de contre-emplacements, sortes d’utopies effectivement réalisées dans lesquelles tous les autres emplacements réels que l’on peut trouver à l’intérieur de la culture sont à la fois représentés, contestés et inversés, des sortes de lieux qui sont hors de tous les lieux, bien que pourtant ils soient effectivement localisables. » (There also exists, probably in all cultures and civilizations, real, actual places, which are delineated in the very establishment of society. They are a kind of counter-place or utopia in which all the other real locations that we find at the interior of our culture are at the same time represented, contested and inversed. They are a kind of place outside of all places, despite actually being possible to locate.) next...

Ben Yehuda Street, Tel-Aviv, Google Street view, 2021

10 Like Bathish’s hotel room, Foucault’s heterotopy is a quasi-place in which culture is reflected and challenged. Later on in Des Espaces Autres (Of Other Spaces), Foucault elaborates on the ability of heterotopies to overlap multiple spaces and locations in a single place: L’hétérotopie a le pouvoir de juxtaposer en un seul lieu réel plusieurs espaces, plusieurs emplacements qui sont en eux-mêmes incompatibles. (The heterotopy has the ability to juxtapose in a single real place multiple spaces, multiple locations that are themselves incompatibles.) Its nondescript materiality creates a sort of overlapping “globalised place” Here again, we find some similarity between Foucault’s heterotopy and Bathish’s hotel room. When I discussed the hotel room with Bathish, he explained that its nondescript materiality creates a sort of overlapping “globalised place”; for example, a Ritz in Dubai resembles that of Athens or London, creating the sensation that you are both here, in a specific location, and anywhere. He went on further to describe how encounters with this globalised place are associated with anxiety. An anxiety that pushes many of the characters to turn on the television, for example in A Room in Amman: ثمة لحظة غريبة ومركبة وكئيبة نوعا ما... تلك اللحظات الأولى التي يجد فيها المرء نفسه وحيدا في غرفة...في فندق... في مدينة ما... لحظة موحشة بغض النظر عن طبيعة هذه الغرفة... أجمل أجنحة برج العرب في دبي أو شيراتون الجزيرة على النيل القاهري الساحر أو دورشستير في لندن أو أحقر نزل في بنغلاديش... ثمة شعور يجعلنا نشعل التلفاز في الغرفة فورا بعد تسلمها وخروج حامل الحقائب منها... حتى في جناح معلّق على أعلى قمم منهاتن... نشعل التلفاز... [Baṭḥīsh, R. (2007). Ghurfa fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p24.] (There is a strange, disconcerting and somewhat depressing moment. Those first moments when one finds themselves alone in a room, in a hotel, in some town. An uncanny moment whatever the character of the room. Be it the most beautiful wing in the Arab tower in Dubai or the Sheraton Al Gezira on the enchanting Cairo Nile or the Dorchester in London or the most wretched hotel in Bangladesh. There is a feeling that make us turn on the television, immediately after we arrive and the porter leaves. Even in a suite suspended among the highest summits of Manhattan, we turn on the television.) next...

Dubai, Ritz hotel, 2021

11 Indeed, screens have a strong presence in the stories; only the stories Claude and Haytham do not feature a television or computer. For Bathish, these screens open up a nonmaterial movement to other places. For example, in Olaa, the dialogue is interspersed with descriptions of scenes on the television: - أنا في رام الله... ولن تصدقني مع من! - نعم؟ - مع عدنان... انه ما زال يحبني يا علا... شكرا... شكرا على المساعدة. هو لا يسمعنا الآن لقد ذهب الى الحمام... - رغد... يجب أن أذهب... يبحثون عني.... كانت الجثث ما تزال تنتشل... وكان الشبان يحطمون مقر الامم المتحدة في بيروت... وكانت كوندوليزا تغلى رحلتها الى لبنان... وكانت الصواريخ قد بدأت تنهمر على الشمال ... وكان الهاتف يرن مجددا. - حبيبتي ها مللت؟ - لا... اشاهد المجزرة. - أنا في طريقي اليك. [Baṭḥīsh,R. (2007) Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyy a li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr, p32.] (“I’m in Ramallah. You won’t guess who with!” “Yes?” “With Adnan, he still loves me Olaa. Thank you, thank you for your help. He can’t hear us now. He went to the bathroom.” “Raghad… I have to go. I’m wanted.” Corpses were still being salvaged. Young people were destroying the UN office in Beirut. Condoleeza Rice was cancelling her trip to Lebanon. The rockets had begun to rain down on the North. The phone began to ring again. “Darling, are you bored?” “No, I’m watching the massacre.” “I’m on my way.”) “Darling, are you bored? –No, I’m watching the massacre.” The use of the past continuous tense, in the excerpt above, emphasizes the simultaneous unrolling of events in different places and, strengthened by the use of a list, makes little distinction between the action happening inside the hotel in Ramallah and in Lebanon on the television screen - indeed they seem to overlap. There is a certain tension around place in Olaa. As we saw above, she is in a hotel “outside of time and place” in Ramallah, but when on the telephone she lies to her mother, who is in Haifa, that she is in Tel Aviv. Later, in a telephone conversation with her friend, who is in Ramallah, Olaa lies that she is in Haifa. The telephone calls, in addition to the lies that the protagonist tells, compound the sense that this hotel room is not only in Ramallah, but also between places or that multiple sites are overlapped within it. Indeed, the nonmaterial movement enabled through means of communication allows for the emergence of a network of places. For example, in A Foam Party, in the Centre of Madrid, the protagonist, Khalil, is travelling back to Haifa from Venezuela; when he checks his emails, he receives messages from people he knows in Haifa, but also in Beirut. In Claude, when Claude, the protagonist, telephones her sisters whilst in Paris, she speaks to one sister who lives in Haifa and another sister who lives in Beirut. Both “Beloved Beirut”, as it is referred to in Haytham, and Lebanon are very present on the television screens, in the emails and telephone conversations of On Countries and Hotels. This is unsurprising, due to the setting of the stories in the 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon. However, as Bathish explained to me, this strong presence is significant in suggesting a sense of belonging and community that surpasses nation-state borders. next...

'Little distinction is made between the action happening in the hotel in Ramallah and in Lebanon on the television screen - indeed they seem to overlap.' Still from 'On Countries and Hotels, taken by the author, Ramallah, 2017.

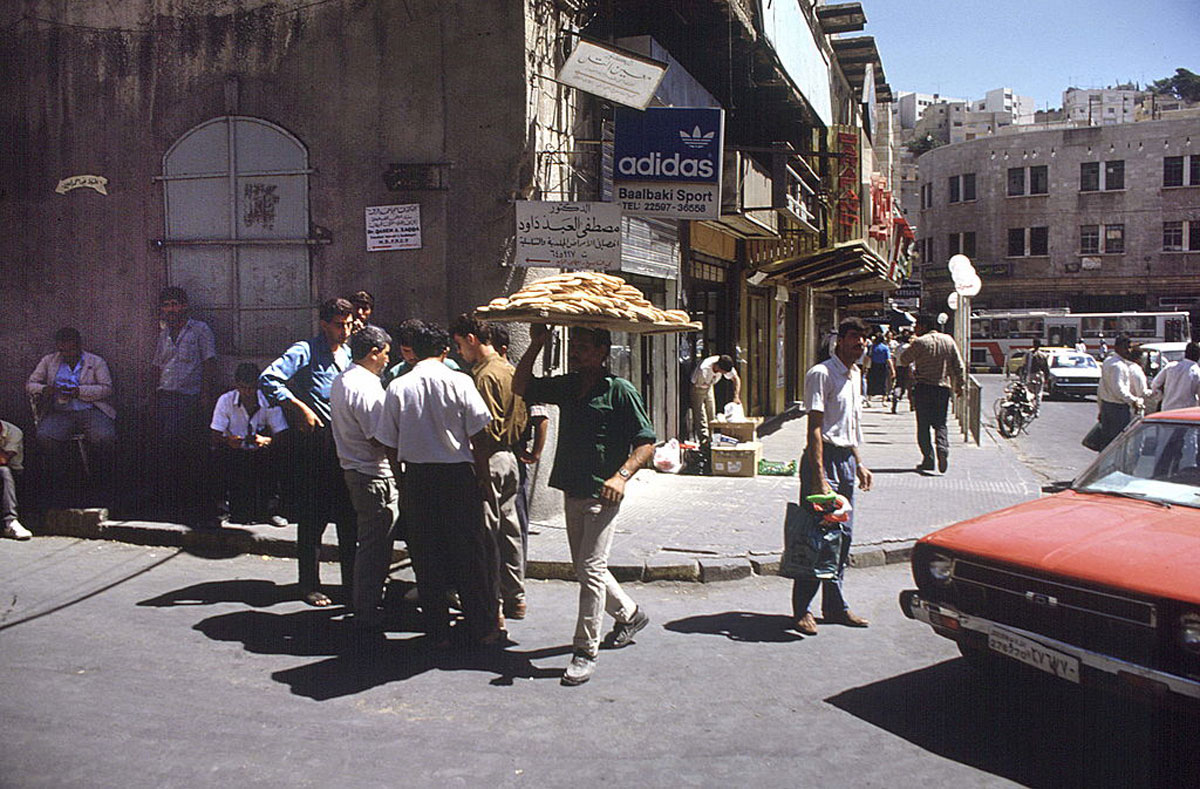

Left: Ramallah, Google Street View, 2021

Paris, rue des Abesses, Google Street View, 2021

12 The hotel is rarely a final destination. Rather, it is a transitory space, providing the backdrop for brief love affairs, as in Intimacy, Olaa, and A Room in Amman, or offering a break in a journey between cities, as in A Foam Party, in the Centre of Madrid, Claude and Haytham. It is only in As If We Were In Another State, that the hotel seems to be the final destination; Jad has chosen Jerusalem as the location where he will commit suicide: لا شيء في القدس أهم منها ذاتها... فما أحلى النهاية فيها أن كان لا مفر منها ذاتها... [Ibid., p15] (Nothing in Jerusalem is more important than the city itself. How sweet it is to end there if there is no escape.) As If We Were In Another State is also the only story with a generous description of the surroundings of the hotel, detailing sights and smells, and even referring to concrete geographical references: كان الصراخ داخل الأجراس أقوى من أية مرة أخرى دخل فيها جاد إلى القدس من قبل... وكانت رائحة الخريف قادم في عز الصيف... ترجل جاد عابر شارع يافا شرقا عبر البلدية والنوترودام ثم اتجه شمالا نحو باب العمود... حيث كان الغروب يزحف مختلفا... [Ibid., p17] (The clamour inside the bells was louder than it had been on any other time Jad had entered Jerusalem. There was an odour of approaching autumn in the glory of summer. Jad took Jaffa Street heading east and passed in front of the municipality and Notre Dame, before turning north towards Damascus Gate, where the sunset crept forward differently.) In the other stories, as we saw above, any description of the surroundings is completely absent or remains very vague. Emphasis seems to be less on the places in which the stories are located, and more on a space produced through material and nonmaterial movement around the network of places and times. To a certain extent, this brings to mind the form of the rhizome, as elaborated by Deleuze and Guattari. Instead of a linear narrative developing in a singular setting, multiple places and times are brought into contact through the space of movement produced in the individual stories and between the stories as a collection: « À la différence des arbres ou de leurs racines, le rhizome connecte un point quelconque avec un autre point quelconque, et chacun de ses traits ne renvoie pas nécessairement à des traits de même nature, il met en jeu des régimes de signes très différents et même des états de non-signes… Il n’est pas fait d’unités, mais de dimensions, ou plutôt de directions mouvantes. Il n’a pas de commencement ni de fin, mais toujours un milieu, par lequel il pousse et déborde. » (Unlike trees or their roots, the rhizome connects any point with any other point; each of their features does not necessarily refer to features of the same nature. It brings into play very different systems of signs and even states of non-signs… It is not made up of unities, but of dimensions, or rather moving directions. It has neither a beginning nor an end, but always a middle, through which it grows and overflows.) next...

Right: On Countries and Hotels, video (excerpt), Raji Bathish, 2017

13 Similar to the rhizome, the space of movement in On Countries and Hotels that déborde, or “overflows”, brings to mind the overflowing time that we explored earlier in this essay. Both resist being ordered by cartography or chronology. However, this does not mirror the space or time experienced by many Palestinians, whose mobility is increasingly restricted under the threat of violence. Literature does not offer a mirror of the world, as Deleuze and Guattari suggest: « Le livre n’est pas image du monde, suivant une croyance enracinée. Il fait rhizome avec le monde, il y a évolution aparallèle du livre et du monde, le livre assure la déterritorialisation du monde, mais le monde opère une reterritorialisation du livre, qui se déterritorialise à son tour en lui-même dans le monde (s’il en est capable et s’il le peut). » (The book is not the image of the world, following a rooted belief. The book makes a rhizome with the world. There is an aparallel evolution of the book and the world. The book ensures the deterritorialization of the world, but the world undertakes a reterritorialization of the book, which deterritorializes at its turn in itself in the world (if it is capable of doing so and it can).) On Countries and Hotels does not claim to mirror a Palestinian experience of space nor try to recreate it in a singular, unifying narrative; instead it illustrates, with love and humour, a rhizomatic space, or a space of movement through a network of places and times, that cannot be delineated in and by societies. On Countries and Hotels suggests that it is possible for a perceived linear order between these times and places to be disassembled and for new relationships to be imagined between them, calling on the agency of the people who inhabit them. next...

Below: 'Mariam narrates, one afternoon in Ramallah', Still from 'On Countries and Hotels, taken by the author, Ramallah, 2017.

14Primary Sources Baṭḥīsh, R. (2007). Ghurfa Fī Tal Abīb. Beirut: al-Mu’assasa al-’arabiyya li-l-dirāsāt wa-l-nashr. Secondary Sources Bakhtine, M. (1978). Esthétique et théorie du roman. Paris: Gallimard. Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The Location of Culture. Abingdon: Routledge. Certeau, M. (1990). L’invention du quotidien, 1 : Arts de Faire. Paris: Gallimard. Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (2013). Capitalisme et schizophrénie, 2 : Mille Plateaux. Paris: Editions du Minuit. Foucault, M. (1994) Dits et écrits: 1954-1988. Paris: Gallimard. Wehr, H. and Cowan, J.M.. (1974) A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Beirut: Librairie du Liban. Online Secondary Sources Bathish, Raji, and Mubayi, Suneela. (2016, 3 May) ‘Occupying the Occupation with Language, Raji Bathish by Suneela Mubayi’ in Makhzin. http://www.makhzin.org/issues/feminisms/raji-bathish-in-conversation-with-suneela-mubayi. Accessed 11 July 2020. next...

15 [1] As part of my masters’ research, I translated ‘An al-bilād wa-l-fanādiq, “On Countries and Hotels” into English and French. I travelled to Nazareth in order to film with Raji Bathish and a number of other collaborators. The process of shooting a film enabled me to reflect not only on the multiple voices, spaces, times and perspectives present in a text, but also on the process of opening out, or regeneration, inherent to translation and transmediation. Instead of becoming a short film, the rushes became the basis of a performance, in which I used multimedia footnotes in order to create an interactive reading of the translation. I presented this performance at an event organised by the artist Madison Bycroft at bologna gallery, Amsterdam, in 2018. I wrote an essay on this process for “Afternoon - In Media Res”, edited by Madison and featuring work from Hélène Cixous, sabrina soyer and Federica Bueti. [2] Bathish, R. and Mubayi, S. ‘Occupying the Occupation with Language, Raji Bathish by Suneela Mubayi’, Makhzin, www.makhzin.org/issues/feminisms/raji-bathish-in-conversation-with-suneela-mubayi, accessed 11 July 2020. [3] Bhabha, H.K (2012). The Location of Culture. Abingdon: Routledge, p201. [4] All translations are my own. [5] “The advancing time poured out with sweetness, in the alleyways of the old city.” Ibid., p17. [6] The importance of which I have explored in another paper “From the hotel room: space, language and translation in Raji Bathish’s ‘An al-bilād wa-l-fanādiq, “On Countries and Hotels”.”, which I presented at “Translational Spaces: Language, Literatures, Disciplines” at St Anne’s College, Oxford, in March 2020 (publication intended for summer 2021). [7] Wehr, H. & Cowan, J. (1974), A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Beirut: Librairie du Liban, p271. [8] Bakhtin borrows the term “chronotope” from mathematics in order to describe the essential correlation between space and time in literature. He suggests that certain literary times take form in certain literary spaces, and visa versa. See: Bakhtine, M. (1978) Esthétique et théorie du roman. Paris: Gallimard, p237. [9] De Certeau describes space as "un lieu pratiqué" (a praticed placed). For example, a field is transformed into a space of play or a pitch when people play football on it. See: Certeau, M. (1990). L’invention du quotidien, 1 : Arts de Faire. Paris: Gallimard, p173. [10] Taking cue from the idea that “space is the effect produced by the operations that orientate it” (See: Certeau, M. (1990). L’invention du quotidien, 1 : Arts de Faire. Paris: Gallimard, p173.), we can understand the illicit affairs in the stories to transform the hotel room into a space of deviancy. [11] In other parts of Salsabil’s fantasy, Bathish also importantly plays on orientalist stereotypes of Arabs as portrayed in European media. [12] Interview with the author, April 2017. [13] Foucault, M. (1994) Dits et écrits: 1954-1988. Paris: Gallimard, p15. [14] My own translation. [15] There is some divergence between de Certeau’s understanding of place, which I am using, and Foucault’s. However, I think Foucault’s heterotopies are nevertheless relevant to us here; the heterotopy, like the hotel room, is localisable and despite constituting a place, like (to a certain level) the hotel room, it is also outside of place, like the hotel room. See: Foucault, M. (1994) Dits et écrits: 1954-1988. Paris: Gallimard, p8. [16] My own translation. [17] Interview with the author, April 2017. Here I do not wish to impose Foucault’s concept of heterotopy on Bathish’s hotel room, but rather draw the two concepts into conversation. [18] Interview with the author, April 2017. [19] Interview with author, April 2017. [20] Each individual story functions as a singular unit. However, it is in reading the collection, and exploring the movement between the stories, that we come to understand the text’s key themes and ideas. Unfortunately, I have only been able to provide quotations from the text in this article. The collection is available in Arabic, but the French and English translations are yet to be published. [21] Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1980) Capitalisme et schizophrénie. 2 Mille Plateaux. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, p31. [22] My translation. [23] Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1980) Capitalisme et schizophrénie. 2 Mille Plateaux. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, p18. [24] My translation. [25] With thanks to Haneen Adi, Ramzi Hazbouni, Mariam Fares and Abby Taylor for their participation in making the video and images. return to the beginning of the article...

On Countries and Hotels

A Time Outside of Chronology

A hotel room in Ramallah

A Space Outside of Place

Notes

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-02-Bottomley-On-countries-and-hotels.pdf