antiAtlas Journal #01 - Spring 2016

RESEARCH, ART AND VIDEO GAMES: Ethnography of an

extra-disciplinary exploration

Cédric Parizot and Douglas Edric Stanley

Cédric Parizot is Researcher in Anthropology at IREMAM (CNRS UMR 7310). He is initiator and coordinator of the antiAtlas of Borders project. His most recent publications are: Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall. Spaces of Separation and Occupation, 2015, Ashgate (co-edited with S. Latte Abdallah) and “Marges et Numérique/Margins and Digital Technologies”, 2015, Journal des anthropologues 142-143 (co-edited with T.Mattelart, J. Peghini and N. Wanono).

Douglas Edric Stanley is an American-born artist and teaches in Aix en Provence where he founded the Atelier Hypermédia, an atelier dedicated to the exploration of algorithms and code as artistic materials. Douglas also teaches Algorithmic Design in the Media Design Master of the Geneva University of Art and Design (HEAD). As an artist, he has participated in several exhibitions related to digital art.

Translated by Caroline Mackenzie.

Keywords : apparatus, art, digital art, distanciation, device (dispositif), ethnography, borders, Intifada, Israel, video games, Palestine, walls, research, mobility regime, procedural rhetoric

To quote this article: Parizot, Cedric, Stanley, Douglas Edric, "Research, Art and Video games: Ethnography of an extra-disciplinary exploration", antiAtlas Journal, 01 | 2016, [Online], published on June 30th, 2016, URL : http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/01-research-art-and-video-games-ethnography-of-an-interdisciplinary-exploration, DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.23724/AAJ.9, accessed on Date

Introduction

1 This article reviews the process of conception and development of a documentary and artistic video game: A Crossing Industry. This game focuses on the operations of the Israeli separation regime in the West Bank during the three years following the second Intifada (2007-2010). Still in development, it is being produced by a transdisciplinary team composed of an anthropologist (Cédric Parizot), an artist (Douglas Edric Stanley), a philosopher (Jean Cristofol) and ten students at the École supérieure d’art d’Aix-en-Provence. In this contribution, we discuss how game video technology has allowed the team to use a documentary approach to model ethnographic analysis, using artistic conceptualization with its own aesthetic and poetic issues.

The framework offered by antiAtlas Journal allows us to put this art-science collaboration into perspective in an original way. Co-signed by two of the game’s conceptual designers (Cédric Parizot and Douglas Edric Stanley), this article incorporates two formats: text and illustrations. I have written the text in the first person, in order to describe my experiences during this collaboration. For the illustrations, on the other hand, we have included some of the photographs and maps that I used when presenting my research to Douglas, Jean and the students; but, above all, they illustrate the outline, the initial attempts in coding dialogue and animation, and the first layouts for the game we have developed together.

Our project for this video game was born at the beginning of 2013. At the time, I was working with Jean Cristofol on the antiAtlas of Borders project. Douglas, a professor at the École supérieure d’art d’Aix-en-Provence, was one of Jean’s colleagues. In bringing us together, Jean wanted to see how our two ventures could be articulated.

For antiAtlas of Borders, I had already envisaged a collaboration with artists as a way of exploring new forms of modelization in my research and of triggering a critique of my own practices in representation (Schneider et Wright, 2006, Dgarrod, 2013). Video games seemed to me all the more attractive in that they act as powerful stimulators (Frasca, 2003) by offering a specific rhetorical and narrative mechanism. Ian Bogost (2007, p. 15) has qualified their rhetoric as ‘procedural’, that is to say an art of persuasion that uses computer systems to construct or deconstruct an argument. In addition, these games have long attracted the attention of social science researchers. They are used in many ways for pedagogical activities (Ruffat and Ter Minassian, 2008) and for the development of new methods of teaching. The potentialities offered by commercial games such as Civilisation III (Squire 2004) and Sim City (Ter Minassian and Rufat, 2008) have been evaluated for the teaching of history and geography. In political science, educational games such as Global Conflict and PeaceMaker are used for placing students in processes of decision-making (Gonzalez et al., 2013). Anthropologists are also interested in the capacity offered by artistic games, such as Every Day the Same Dream, for teaching and guidance (Marinescu-Nenciu, 2015). These studies have, in addition, helped structure a new field of research, Digital Games-Based Learning (Neville and Shelton, 2010). Finally, academics have attempted to develop their own applications: in order to teach history, Kevin Kee (2011) has been directly involved in the process of creating a game and has made an effort to reflect on the aesthetics of this form of expression.

next...

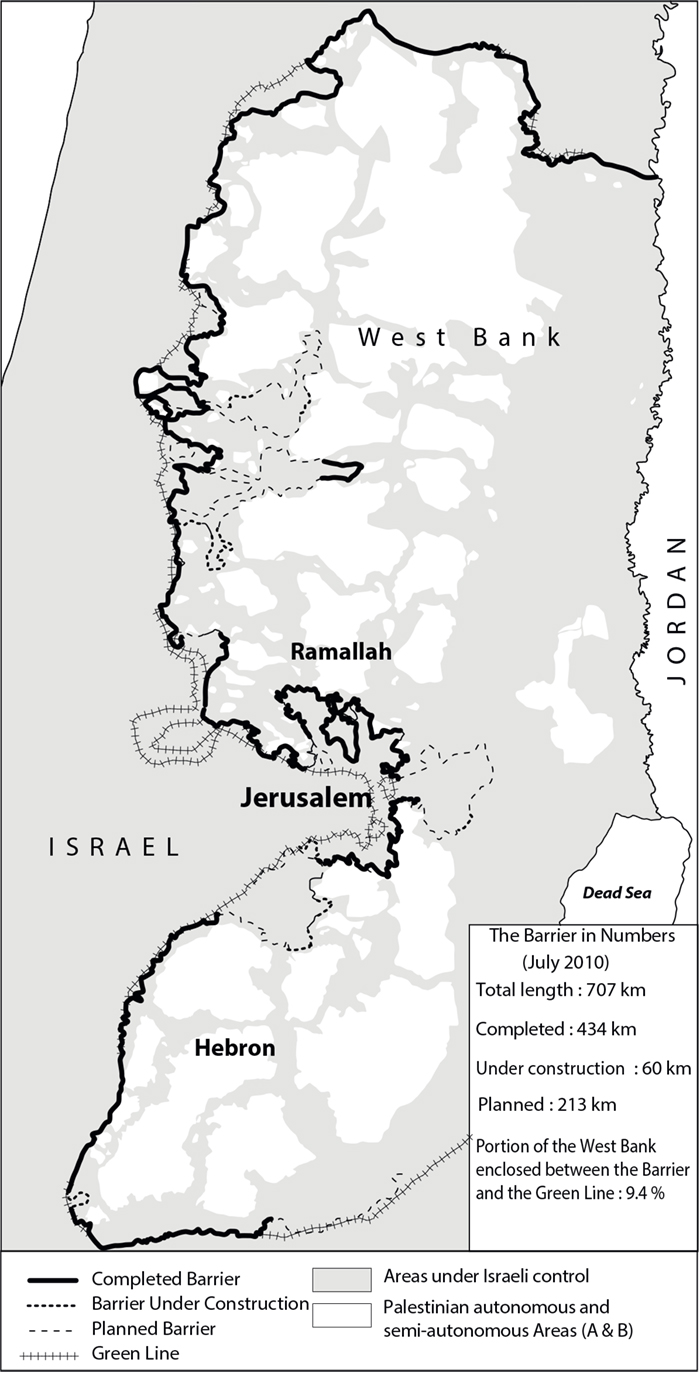

Map of the West Bank (2010) © M. Barazani, CRFJ.

Map created by Ocha Information Management Unit 2010, Data base Ocha, PA, MoP

2 Like many other artists (Bogost, 2007, Flanagan, 2009, Perderson, 2010), Douglas has for several years taken an interest in the importance of rhetoric and aesthetic language in games. Through playing with the codes and formats of games, he has sought to challenge his audience with performances that question their cultural and ideological conceptions. In particular, between 2001 and 2006, he produced several varieties of an installation known as Invaders! which reconstructed the events of September 11th 2001, but within the Space Invaders. For him, despite the substantial success of ‘independent’ games in recent years, video games have suffered from a somewhat condescending discourse and aesthetics. Douglas envisaged our collaboration as an opportunity for exploring significantly rich content with his students, while pushing at the limits of ‘game’ and ’art’.

As A Crossing Industry is still being developed, our objective here is not to evaluate its capacity to communicate a message to a designated audience, but rather to understand how this art/science experiment affects game designers. The process of conceptualization for A Crossing Industry is seen as an artistic device (dispositif) (Fourmentraux, 2010) and a critical documentary (documentaire critique) (Caillet, 2014). Comparing our approaches allows us to highlight the irreducible differences that exist between them and, at the same time, trigger a series of critical analyses of our methods of access to and construction of reality. This analysis does not have any pretension of contributing to debates on Games Studies. Rather, our priority is to review an exercise in extra-disciplinarity, as defined by Brian Holmes (2007), of particular interest for both anthropology and artistic creation.

To provide a more precise idea of our approach, I want first to present briefly a number of video games of the last 25 years that use the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for their context. I will then review the art-science devices (dispositifs) we established and the methods for using these arrangements to assemble together scientific and artistic proposals. Finally, I will show how, in seeking ways to reduce the gaps between our proposals, we had to re-consider the game’s potential for articulating academic statements, but at the same time we discovered its strong capacity of appeal.

next...

I. Entering A Minefield

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has inspired many video game designers. The Israelis and Palestinians are not alone: Americans, Syrians, Lebanese, and Iranians are also working in this niche sector (Šisler, 2009). As one might expect, the market is highly polarized: whether they are created by production companies with substantial resources or by independents, most games are clearly positioned on one side or the other, while criticisms and reactions to their launch are often very virulent (Tawil Souri, 2007, Yaron, 2014). Attempts to challenge dominant visions and narratives about this conflict certainly exist, but they are much rarer. In 2006, Digital Art Lab in Holon, Israel, organized Forbidden Games (Danon and Eilat, 2006) an exhibition where, of all the games presented, only one (Global Conflict Palestine) offered a real reflection on the construction of narratives about this conflict. A Crossing Industry contributes to the extension of this reflection, while taking a very different approach in a number of ways.

a. A very polarized scene

4 The most common games are war games. My intention here is not to give an exhaustive list, but to present the narratives that these games have helped maintain over the period that we are interested in, i.e. from the first Intifada (1987-1993) to today. As Víc Šisler (2009) has shown, even though Israeli and Palestinian war games defend radically different positions and visions, the game play in both uses a similar meta-narrative focusing on the confrontation between two peoples.

In 1989, an Israeli, Mike Medved, designed one of the first games about the conflict: Intifada. This game involves an Israeli soldier caught between Palestinian demonstrators and his government. The player’s objective is to disperse the demonstrations by killing and wounding a minimum number of Palestinians in order to avoid the election of a left-wing government (Yaron, 2014). According to Danon and Eilat (2006), this game expresses a very Israeli-centric perspective: the idea of being alone against the world, the image of a David and Goliath combat. New games on this theme of confrontations between Israelis and Palestinians were not produced until 2014, one example being Bomb Gaza (2014) in which the player must drop as many bombs as possible on the Gaza Strip, while avoiding civilian casualties and being hit by missiles fired by Hamas. When launched, the game generated such strong reactions that Google and Facebook were forced to remove it from their platforms (Guardian, 2014).

In Israel, some think tanks have paid very serious attention to the political role that video games can play.

In Israel, some think tanks have paid very serious attention to the political role that video games can play. In 2015, the Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) deplored the fact that the Israeli video game industry had not invested enough in this sector. JPPI suggested the Israeli Government should support this market by encouraging the production of games promoting a positive image of Israel and combatting new attempts at “delegitimization” by the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions Movement (BDS). It also suggested that the army could set a “good example” since it had created an interactive game called IDF Ranks, set during the 2014 Israeli offensive in the Gaza Strip. In this game, the player scores points every time he reads, comments, likes or shares information provided by Tsahal’s spokesperson and works his way up through the army ranks (JPPI, 2015, p. 243).

next...

Cover of the video game Intifada by Mike Medved, 1989, http://www.mobygames.com/game/intifada

Clip of the video game Bomb Gaza (2014) posted by DrumTwoDaBass on Youtube.

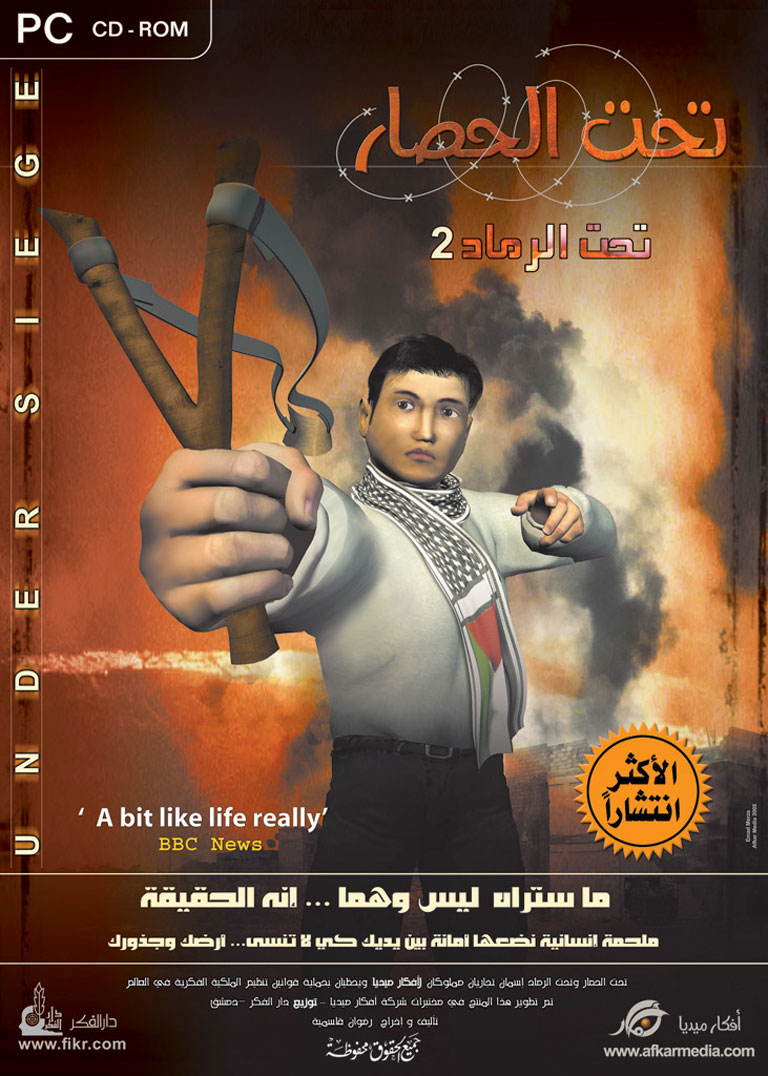

5 The first games clearly taking up the Palestinian cause, Under Siege (2001) and Under Ash (2003), were produced by a Syrian company, Dar al-Fikr. As a first-person shooter game, the initial scene of Under Siege takes place in the Mosque of Abraham at Hebron in 1994, the moment before the Israeli settler Baruch Goldstein assassinated several dozen faithful Muslims at prayer: the player must avoid the bullets and kill the shooter as quickly as possible. In other scenes, he finds himself in demonstrations facing the Israeli army with only a slingshot for a weapon and he cannot progress through the levels until he has obtained automatic guns. Under Ash, on the other hand, focuses more on the Second Intifada (2000-2004) (Tawil Souri, 2007).

A radical change in perspective

As with many other games in the market, graphic designers insist that they maintain a close relationship with reality (Šisler, 2009) in order to convince the public of the validity of their message and the immersive character of their game (Höglund, 2008, quoted by Šisler, 2009). Under Siege and Under Ash include documentary-style narratives, interviews and reports from several Palestinians, together with data from the United Nations (Tawil Souri, 2007, p. 549). Nevertheless, the objective of these games is not so much to provide a documentary as to achieve a radical change in perspective: by taking on the identity of a Palestinian, the player is no longer condemned, as was long the case in games dominating the market, to taking the role of a member of an American, European, or Israeli security forces for whom the enemies are usually Arabs (Donan and Eilat, 2006). In addition, rather than reduce Palestinians to playing the victims, these games show them as resistance fighters (Tawil Souri, 2007).

The creation of online platforms (Google Play, Apple AppStore, etc.) for smartphone applications seems to open new scenes where Israelis and Palestinians can fight with each other. It was the case during the brutal conflict between Israel and the Gaza Strip during the summer of 2014 (Paillot 2014). On the Palestinian side, three games were launched on these platforms: Gaza Hero, Gaza Man and Free Palestine. Each simulated, in their own way, the population’s struggle against the Israeli offensive: in Gaza Man, a Palestinian armed with a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) fires at tanks, soldiers and planes; in Free Palestine, the player moves through Mario-style platforms while avoiding obstacles such as ditches, fireballs and Israeli soldiers; finally, in Gaza Hero the player touches Israeli tanks, planes, boats and ships and transforms them into bread, cakes, sandwiches, bottles of water for the besieged Palestinians. I should also mention The Liberation of Palestine developed in Gaza and launched in 2014 by its designers as a “way of developing the spirit of resistance among Palestinian youth” (Yaron, 2014). These games see themselves as the Palestinian counterpart to pro-Israeli games such as Bomb Gaza, Whack Hamas and Gaza Assault (Paillot, 2014) which Google and Facebook were forced to remove from their sites because of the uproar they generated.

next...

Poster for Under Siege 2 (2005), source: http://kotaku.com/5654958/a-game-about-insurgency

Clip of the video game Under Siege (2013) posted by Derek Gilda on Youtube.

Clip realized by the Middle East Media Resarch Institute, New Palestinian Computer Game Teaches Players: Armed Resistance, Not Negotiations,

clip #4567, October 19th and 22, 2014.

b. Problematizing or documenting the conflict

6 Educational games, in addition to those reproducing conflicts, are being developed. Their aim is to offer a much more problematized approach to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: for example, Global Conflict, Palestine (Serious Games, 2007) and Peace Maker (Impact Games, 2008).

Global Conflict (see adjacent video) provides a critical reflection on the conditions for developing journalistic information in the field. The player takes on the role of a reporter who must collect information from Palestinians and Israelis and report on his findings without upsetting the expectations of his readers (Israelis, Palestinians or Westerners). Depending on the questions the player asks, the empathy he expresses, and the help he offers his interviewees, their confidence in him changes, and the quality of information they agree to give them improves. What is interesting in this game is that it demonstrates the complex relationships linking these populations and the impossibility of remaining a neutral and distant observer. In addition, these interviews reveal the negotiable nature of information and the situated nature of constructed reality (Šisler, 2009).

A critical reflection on the conditions for developing journalistic information

On the other hand, PeaceMaker insists on the multiplicity of actors and, thus, the difficulty of modelizing the factors and processes at work in structuring the conflict (Gonzalez et al., 2010). Nevertheless, with the player taking the role of political decision-maker, it moves him away from the experiences of the populations and the complex relations they develop in their daily lives: the player can become either the Israeli Prime Minister or the Chairman of the Palestinian Authority. His objective is to take pertinent decisions that will advance the peace negotiations, while dealing with international pressure, negotiating conditions imposed by various funding organizations, and destabilizing problems provoked by operations carried out by Palestinian armed groups, raids by the Israeli army, settlers, and pressure from public opinion. Another interesting factor in PeaceMaker is the way it highlights the unequal rapports de force between the two parties. Thus, while the Israeli Prime Minister can control checkpoints, impose periods of curfew, order the destruction of houses, and military strikes, the Palestinian Chairman has only limited powers (Šisler, 2009).

Finally, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has inspired games commissioned by human rights organizations: for example, Safe Passage, produced by Gisha in 2010. Gisha is an Israeli non-governmental organization founded in 2005 with the objective of ensuring that Palestinians have freedom of movement as required under international and Israeli law. The game’s objective is to inform the public by giving players an interactive opportunity to test for themselves the restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. It includes a dozen official documents and decrees issued since the early 1990s, when Israel imposed the first restrictions on the Occupied Territories.

The player has three options when choosing her role: a woman in Gaza seeking to study at the Birzeit University (West Bank); an ice-cream salesman interested in setting up a business in the West Bank; and finally, a man separated from his wife and child after being arrested in the West Bank and transferred to Gaza. In order to understand the rules and procedures the protagonists must negotiate, the game does not use a realistic perspective, but creates a more poetic fictional scenario. For example, when blocked at the exit from the Gaza Strip by an image in trompe-l’œil, the Palestinian student can choose to apply for an exit permit either directly to the Israeli army, represented by a post box wearing a beret, or to the Palestinian Civil Affairs Office, represented by a robot’s hand, or take her case to the Israeli Supreme Court, represented by a gavel with glasses. These symbols demonstrate that the student can never interact with real persons, but only with a Kafkaesque bureaucracy that leaves her with little room to manoeuvre. Taking only fifteen minutes to complete, Safe Passage offers a very effective way of making people aware of the restrictions that Palestinians have to face.

Similarly, A Crossing Industry moves away from the armed conflict scenario and focuses on the day-to-day interactions between Palestinians and Israelis in the occupied West Bank.

next...

Clip of the game Global Conflict, Palestine (2007), posted by SeriousGamesdk on Youtube.

Clip of the game Safe Passage (2010) posted by Otraverdad on Youtube.

c. A Crossing Industry: a polemic approach

7 The story for this game centres on a young Palestinian man who returns to his home village just after the Second Intifada (2000-2004). After several years abroad, he discovers not only that the village is now blocked in by Israeli settlements and the Wall of Separation, but also that restrictions on movement around the village have been tightened. But the Israelis are not the only people to introduce regulations on the movement of people and merchandise. As he rediscovers his bearings, he learns about a total informal economy of negotiation and passage which involves Palestinians, Israelis and sometimes people of other nationalities.

next...

Runners in the Palestine Marathon, part of the route passes through the Aida refugee camp

(West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territory). Photograph by Agnès Varraine-Leca, 2014

View of the Separation Wall from a roof in the Aida refugee camp (West Bank).

Photograph by Agnès Varraine-Leca, 2009

8 Using the game simulator, A Crossing Industry seeks to modelize types of interactions put in place by various actors (Palestinians and Israelis) who interact in the shadow of the wall and influence, each in their own way, how the separation regime operates. Instead of ending interactions between Palestinians and Israelis, the separation policy has in fact transformed, since its introduction in the 1990s, and multiplied the potential for intermediation (Garcette, 2015; Latte Abdallah and Parizot, 2015).

In order to travel and partake in social and economic activities, Palestinians must regularly seek help from contacts or professional smugglers to circumvent the obstacles and systems set up by Israeli surveillance agencies. Smugglers take advantage of these constraints and have developed a very lucrative business. Not only do they facilitate passage, they also impose their own informal rules. Relying on networks of Palestinians in the West Bank, Jerusalem and Israel, as well as Israeli Jews, these “entrepreneurs without borders” contribute to the reorganization of relations between the two populations and to a complexification of the separation regime’s operations (Parizot, 2014).

next...

The Tigers of Jinbah, anonymous video showing the driving skills of young Palestinians

transporting unlicensed workers into Israel, 2010

Young Palestinian pupils (South West Bank) checking the road to their school for roadblocks by Israeli settlers. Photograph by Eduardo Sorteras, 2010

Israeli army Hummer, South West Bank. Photograph by Jérôme Bellion, 2010

9 While Safe Passage takes a legal approach to regulations and restrictions of movement imposed by Israel on Palestinians, A Crossing Industry offers a practical approach to these operations. The separation regime is no longer envisaged merely as a technology of power, but as the result of an interaction between a powerful actor (the State of Israel) and the tactics of weaker actors (Palestinian Authority, smugglers, Palestinian citizens, etc.) who are condemned to live in their opponent’s time and space.

A Crossing Industry does not seek to take an educative or militant role or to offer a so-called neutral view of the situation: it offers an ethnographic and artistic perspective

A Crossing Industry does not seek to take an educative or militant role or to offer a so-called neutral view of the situation: it offers an ethnographic and artistic perspective. Based on field research in Israel and the West Bank between 2005 and 2010, it interprets social, economic and political processes. Indeed, this analysis was based on both my network of relationships and the emotional attachments I developed in the field (Parizot, 2012) as well as on other academic research. At the same time, by modelizing this analysis through a game and a story with strong aesthetic and poetic undercurrents, Douglas wanted to show how, in order to be effective, ‘serious’ games must include a strong playful and poetic dimension. From his point of view, their disruptive capacity comes from the ambiguity generated by the confrontation between the ‘useless’ character (Huizinga, 1951) and the gravity of subjects and stories that games portray. From this perspective, A Crossing Industry can be seen as a polemical game, to use Eddo Stern’s term (UCLA, 2016): that is to say, a game which, by taking a dual perspective, seeks to generate debate rather than to convince.

next...

II. Conceptual Design Of The Game: A Social Interstice

10In seeking to articulate our scientific and artistic hypotheses, we have opted for a collaborative and non-cooperative approach, i.e. co-production of an artwork. We wanted to avoid any sense of hierarchy in how we worked together, that is to say the artists do not act as performer in the modelization of a scientific project, and the researcher does not play the role of consultant in the creative process. Our objective was to open up a social interstice, defined by Nicolas Bourriaud (2002) as an empty space/time, that allowed us to appreciate the differences between our two approaches and, as a result, explore them more effectively through a series of exchanges and juxtapositions other than those recognized as legitimate in the fields of art and research.

a. Scientific proposals and artistic proposals

11Our initial reflections on the content and the format for our game took place at the École d’Art d’Aix-en-Provence. We regularly met at Douglas’ Hypermedia Workshop (Atelier Hypermédia), where he and his students experiment with programming in their artistic practices. In order to familiarize them gradually with my field research, I began by presenting my analysis of the way Israeli control mechanisms operate in the West Bank and of the complex territorial situations they have shaped since the 1990s. For this purpose, I gave them a series of oral presentations and provided them with articles and graphic documents (maps and photos). At the same time, the students showed me materials such as films, press articles, works of art about the conflict in order to discuss them with me.

Next, Douglas and four students from the workshop (Tristan Fraipont, Emilie Gervais, Martin Greffe, and Matthieu Gonella) began their reflections on the conception of a graphic language and the first animations in order to objectivize and incorporate my research findings in the game. They also sought better ways to situate this language, compared to existing options, by reviewing, playing, analyzing and discussing various other games. They put forward examples from past video games, including some with a strong narrative: textual games (Oregon Trail, Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium 1971/1979), adventure games (Zelda, Nintendo, 1986-2002, Another World, Eric Chahi 1991, Alone In the Dark, Frédérick Raynal, Infogrames 1992); and enigma games such as Myst (Cyan 1993). They also investigated experimental, artistic and ‘independent’ games including Passage (Jason Rohrer 2007), Waco Resurrection (Eddo Stern et al. 2004), Kentucky Route Zero (Cardboard Computer 2003), and Proteus (Ed Key & David Kanaga 2013). They reviewed best-selling games, such as Tomb Raider (Eidos Interactive 1996/2013) and Red Dead Redemption (Rockstar Games 2010). Finally, they suggested forms of representation and messages deployed in games linked to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (see part 1) and the question of borders (Frontiers the Game, Gold Extra 2012, Papers, Please, Lucas Pope 2013).

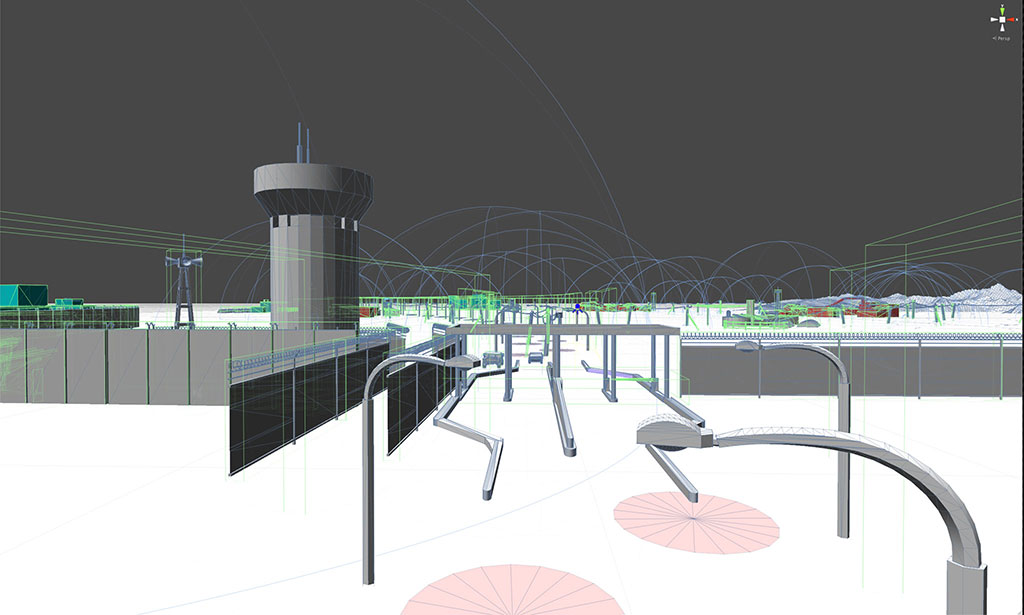

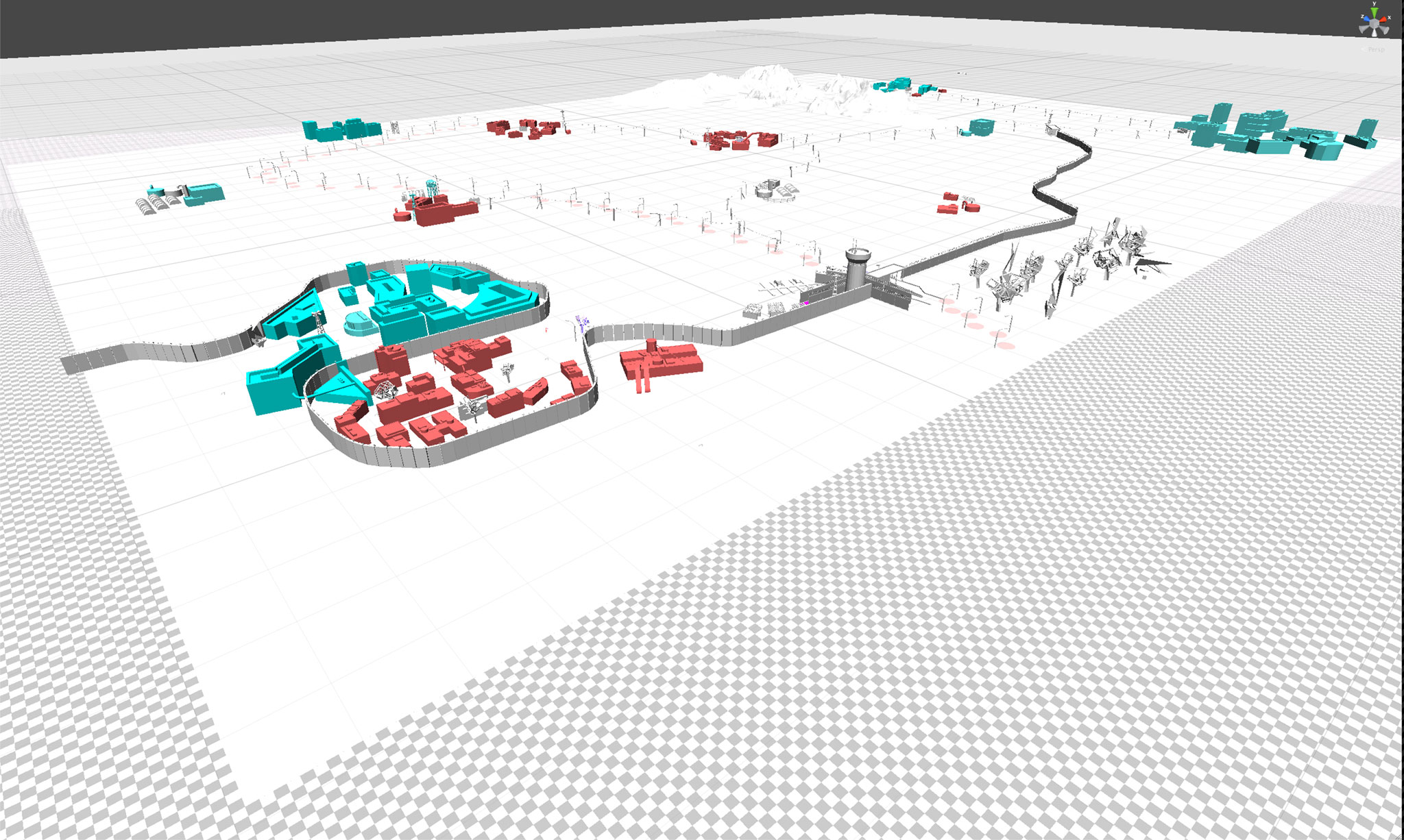

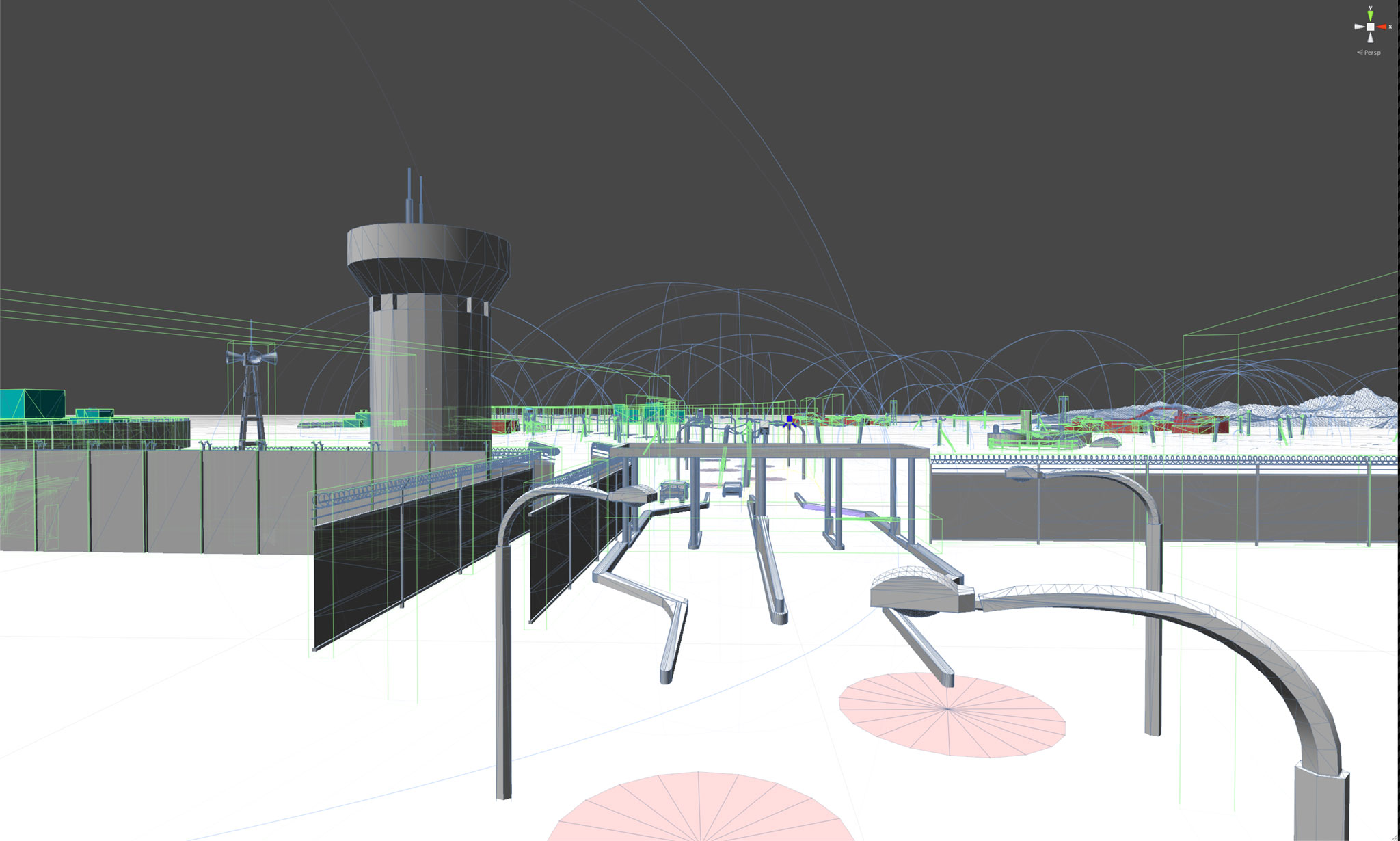

In October 2013, the project finally adopted a graphic language which uses low-poly 3D objects, a single background with grey nuances (empty with no visible ground) and primary colours for representing different types of places (Israeli-controlled zones, Palestinian zones, etc.) and the specific status of individuals (Palestinians, Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, Israeli Jews, soldiers, border guards, etc.). By placing these objects on a map similar to the one I had drawn, we were able to develop the first layout for the navigational space.

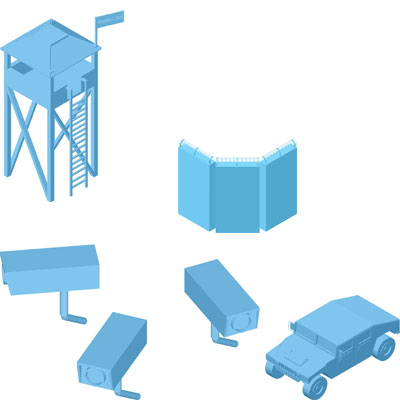

While some elements were designed directly in Sketchup and Cinema4D by Matthieu Gonella, others were taken from the Internet and readapted for the game. In September and October 2013, we added more visual elements (checkpoints, barriers, barbed wire, lampposts, etc.) and a soundtrack composed by another student, Bastien Hudé. Development of the game’s space and the integration of these elements were achieved using Unity, a commercial game engine with a free component that can generate applications for various platforms (Mac, Windows, Linux, smartphones, tablets and game consoles).

next...

Gate inserted into the separation barrier, South West Bank. Photograph by Cédric Parizot, 2006

Wadi al-Khalil/Meitar Checkpoint, Palestinian side, South West Bank,

Photograph by Jérôme Bellion, 2010

Second proposal for the game’s map. Mathieu Gonella, Douglas Stanley, A Crossing Industry, 2014

3D low-poly elements created by Mathieu Gonella, 2013

b. Disparities

12 The code, video game engine, and graphic language have played a central role in mediating between our scientific and artistic approaches. For the artists, these tools allowed them not only to express but also to objectivize the scientific knowledge that I had provided. Similarly, these same elements allowed me to evaluate the way in which my ideas had been integrated and transcribed by the artists. Nevertheless, this process did not lead to a reconciliation of our artistic and scientific approaches. On the contrary, the first draft made us realize that there were substantial gaps between my scientific proposal and the artistic conceptualization developed by Douglas and the students.

The initial disparities were due to the cultural and material conditions that shaped the sharing of knowledge. The way that Douglas and his students viewed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict played an important role in how they understood the information I gave them and in their first attempts to objectivize it. The oppressive tone of the soundtrack and the graphic environment used in the first draft reflected the artists’ representation of the situation, more than my own.

The human, material and financial conditions available also had an impact on the disparity between the initial project and the first graphic proposal. In the beginning, we had envisaged a multi-player structure which would allow several people to play online simultaneously and take on different roles (smugglers, workers, border guards, etc.) and a scenario that could evolve as a result of their interactions (Parizot and Stanley, 2014). We finally opted for a game with a single player who takes the role of a Palestinian worker from the West Bank whose objective was to circumvent the surveillance systems in order to go and work in Israel.

I could no longer remain in my role as transmitter of knowledge, while the artists needed to objectivize that knowledge through the coding of a visual language, text and rules of interaction.

Much more significant was the indissoluble gap between the scientific proposal and the artistic proposal. As an anthropologist, I initially saw the game as a scientific documentary, as a particularly innovative form of writing that could construct an explanatory model through new operations and a new environment. Indeed, I thought that this first attempt at creating a navigational space would act as an alternative map displaying the complex territorial forms that have prevailed in the Israeli-Palestinian space since the end of the Second Intifada. From their perspective, Douglas and the students saw the game as an artistic production. Their first proposals focused more on their desire for aesthetic coherence and on how they themselves positioned their work within the field of video game creation. The choice of a minimalist décor was in fact an attempt to set this game apart from other games which use a realist environment.

At this point, we realized that we had to rethink our respective positions. I could no longer remain in my role as transmitter of knowledge, while the artists needed to objectivize that knowledge through the coding of a visual language, text and rules of interaction. We had to give much greater thought to understanding how we could work through these difficulties.

suite...

III. The Game As Critical Documentary

13 We explored several options for articulating these propositions. On my side, I attempted to appropriate the graphic language provided by Unity and the software for writing scenarios. The reflections generated by these attempts allowed me to make a critical appraisal of the hegemonic character that I had given to certain regimes of visibility, such as cartography. They also allowed me to understand the contingent and intersubjective nature involved in constructing an argument through a video game. Finally, they contributed to a rethinking of the various forms of intervention that A Crossing Industry could offer. This is in fact how the game was able to assume fully its role as critical documentary (Caillet, 2014): not so much because it could document a situation in the field, but because it forced us to reflect on our methods of accessing and constructing a reality.

a. The hegemony of the map

14 Given how little I know about computer science, I left it to Douglas to look after the 3D programming. While I worked with him and the students in choosing their proposals and checking that these were not too radically different from my scientific concept, I had neither the capacity nor the authority to give an opinion on the project’s artistic coherence. Therefore, I had to understand and familiarize myself with these graphic elements if I was going to see how to use them to display the complexity of territorial situations in the Israeli-Palestinian area. I gave this graphic language a new sense which was superimposed, and sometimes articulated with, that already being used by the artist and students.

Although I had been seduced and destabilized by the minimalist and oppressive universe that Douglas had shown me in the first draft, I quickly discovered the advantages in using the simplified 3D version. By creating a fictional environment, we could make A Crossing Industry different from other games, which had fallen into the trap of creating a realist illusion, by reducing reality to an environment that could be seen independently from the position of the actor and the apparatus through which he experiences it. With a fictional universe, A Crossing Industry from the outset stressed the irreducibility of reality to an animated landscape.

next...

A Crossing Industry, visual created by Douglas Edric Stanley, 2014

15 Next, by using a minimalist fiction, our graphic language allowed us to pare everything down to the essentials, retaining only the most characteristic elements we wanted to highlight in the map. I was able to put forward the hegemonic landmarks, i.e. the infrastructures and status (of persons and places) that, given their materiality, are seen essential for all actors. On the first map, we displayed the residential zones, the Israeli infrastructures of control (wall, checkpoints, watch towers, road blocks, etc.), and the stark colours indicating the identities and status ascribed by the Israeli administrative system to Israelis and Palestinians. Blue was used for Israeli Jewish citizens, red for Palestinians from the Occupied Territories, and orange for Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, etc. Different colours were attributed to representatives of Israeli and Palestinian authorities as a way of distinguishing them from the rest of the population: brown for private security companies’ guards, grey-green for border guards, green for soldiers, etc.

Demonstrating the blurring of spaces generated by the proliferation of temporary borders and control systems in the West Bank.

The initial animations of this landscape were seen as a way of demonstrating the blurring of spaces generated by the proliferation of temporary borders and control systems in the West Bank. This allowed me to insist from the start on the limits inherent in a cartographical and institutional reading of Israeli-Palestinian spaces. A video of a second version, which was exhibited at Ferrara in Italy in October 2014, opened on an Israeli checkpoint where cars could cross and people of different colours crowd around. A drone passes overhead and the camera moves to the left, flies over and slowly displays a minimalist landscape criss-crossed by walls and roads separating or linking residential zones coloured red and blue. It then flies over the wall and zooms in on a person in red standing in a village surrounded on three sides. A cursor in the form of a cross appears allowing the player to enter into this new universe.

The flooding of the graphic environment with control systems (walls, barriers, checkpoints, watch towers, etc.) and multiple demarcations demonstrates the way that territories are solidly interlinked. Similarly, the presence of people of different colours at the checkpoint – e.g. red people in blue areas – reinforces this feeling of interpenetration of living areas by both populations and challenges territorial dimensions of separation.

next...

Video of the second version of A Crossing Industry made by Tristan Fraipont, 2014

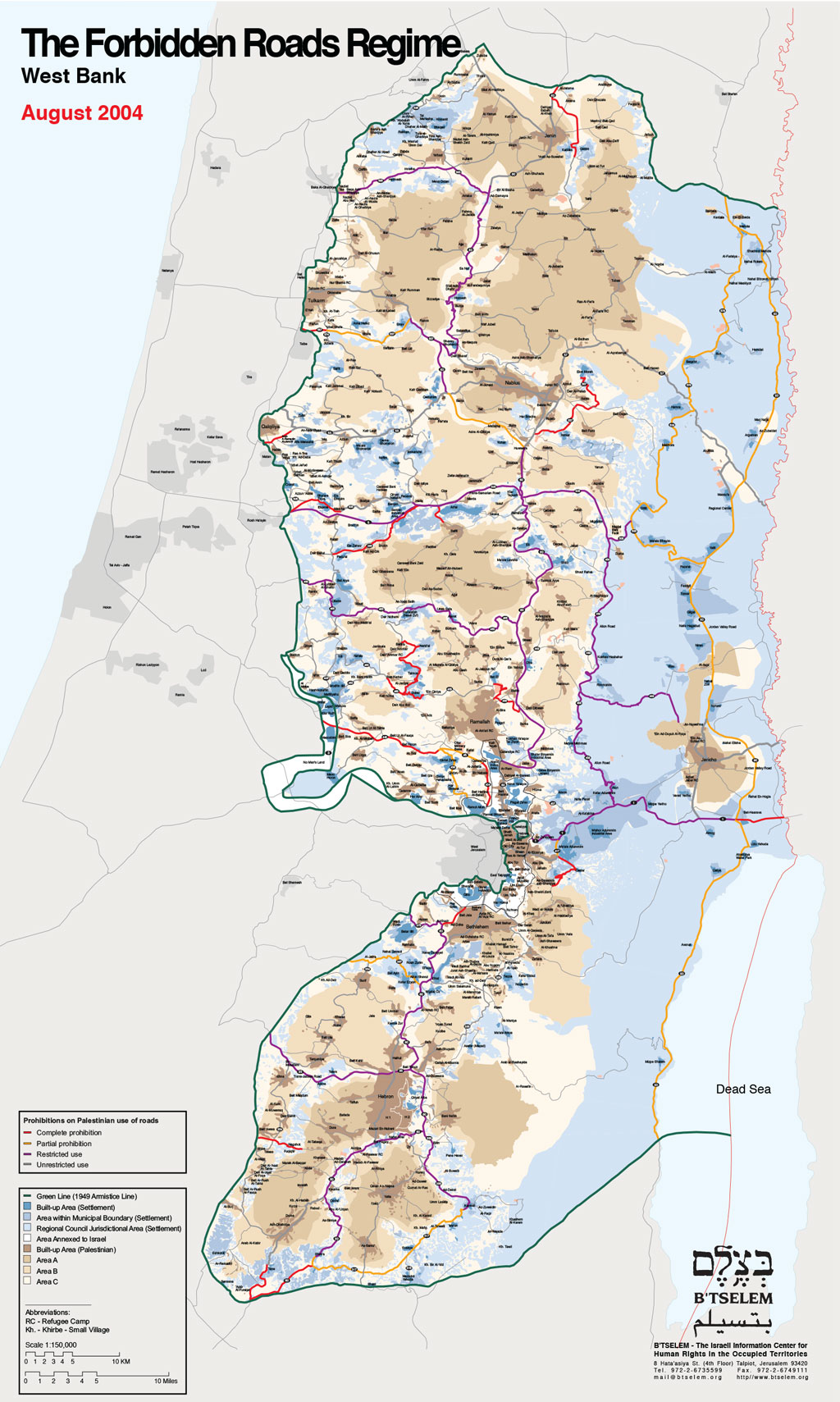

B’tselem, map of the West Bank showing restrictions imposed on Palestinians

on West Bank roads, August 2004

16 As I began to understand the possibilities offered by the video game, I became increasingly ambitious. I even thought of displaying the asymmetric use of space by Israelis and Palestinians in space and time. In fact, Israeli control systems tend to redistribute the movement of Israeli and Palestinian populations not only in different areas, but also along different time period during the day. In the 1990s, the Israeli authorities installed a network of ‘bypass’ routes linking Jewish colonies to Israel without passing through Palestinian towns and villages. During the Second Intifada, several of these roads were banned to Palestinian vehicles thus accentuating the separation of the two populations in their circulation through the territory (B’Tselem, 2004). Although most of these access restrictions were lifted in the years following the Second Intifada, the army continued to deploy roadblocks in numerous places in order to disassociate the movement of both populations (Handel, 2009). Alongside this spatial separation, there is also a temporal separation. Israeli settlers usually travel at periods linked to their work schedule. Although these periods are often the same as for Palestinians, Israelis find it easier to drive along the roads and through cross checkpoints in the West Bank and can afford to leave home at reasonable hours. However, Palestinian workers have to start out much earlier because they have to allow plenty of time for unforeseen delays, controls and long queues at checkpoints.

While it was technically possible to include these temporal issues in A Crossing Industry, there was a high risk that the game would become bogged down in a cartographic representation of space. For, even if the game’s clock makes it possible to define different rhythms and periods of movement for each population, it stages them on a map which remains “a-chronical” (achronique). This staging would thus only realize a dynamic spatialization of people’s movement, reducing their specificity and asymmetry to their rhythm, their orientation and the period of time in which they would take place. Yet, as Michel De Certeau (1990, p. 59) explains, even a dynamic spatialization cannot show how each individual constructs his own relationship with space; a relationship that assembles temporally, culturally and emotionally the places he passes through during his daily journeys.

Even a dynamic spatialization cannot show how each individual constructs his own relationship with space.

This is where I understood the contradictions between my ethnographic approach in the field and the cartographic perspective in which I seemed to be imprisoning myself through my personal analysis. Even though, in my field studies, I had concentrated on how people living in this region organized their daily routines differently, cartography continued to serve as the main framework through which I tended to project and represent them. Even though my efforts to understand Douglas’ graphic language and the game’s regime of visibility, this still did not allow me to envisage an alternative or more efficient perspective than the map, they had nevertheless helped me to become aware of the disparities between my hypotheses and the regimes of visibility that I habitually use in my research.

next...

b. Intentionality, intersubjectivity and code

17 In order to have a better understanding of how a video game could help build up an argument, I consulted a number of theoretical publications and, in particular, those of Gonzalo Frasca (2003) and Ian Bogost (2007). Like Gonzalo Frasca, I began to see games as simulators that allow us to reproduce complex interactive systems in reduced environments and yet still retain their main characteristics. I was particularly intrigued by Bogost’s theory of procedurality (2007) that considers that video games are imbued with a strong power of persuasion through the encoding of interaction rules. By immersing the player in a series of interactions, the game allows the development of a narrative in real time, i.e. a narrative based on the player’s actions, rather than as a sequential and predetermined organization of texts, images and animations like books, films or some exhibitions (Gattet, 2014). By discovering what was possible or impossible, the player gradually takes into account the rules governing the universe reproduced in the game. As discussed by Aline Caillet (2014, p. 61), with regard to certain practices in documentary films, video games could be seen as a way of reactivating, rather than representing, the process:

“the use of games — in the sense of performing, redoing through gestures — appears as what allows the constructing of the actual scene, that it does not represent — nor even reconstitute — but re-enact a past that is, in itself, impossible to describe.”

My objective was thus to code a scenario in order to simulate the way that formal and informal rules shape the movement of Palestinians and Israelis in the West Bank. As a test, in September 2015, Jean and I tried to code the moment when the player is stopped by a mobile checkpoint.

The difficulty here was to recreate the unforeseeable, and sometimes arbitrary, attitude of guards at checkpoints. We used the software tool Twine for our trials. We provide here a playable version in text mode. By manipulating the different variables, we managed to define the type of control that would be triggered within the game according to the authorities the player meets (police officers, border guards, soldiers, etc.), the direction in which he is travelling (is the player driving towards an Israeli zone or to a Palestinian enclave?), the documents he can produce (Israeli work permit or not) and his form of transport (in a car, on foot). The introduction of arbitrary reactions by the authorities opens up a whole range of different interactions and scenes, as well as the unpredictable character of their attitudes. Finally, by repeating these control scenes with quite different outcomes – simulated in this textual version by circling back to the beginning of the same scene – seeks to put the player in a situation where he has to confront the arbitrary atmosphere resulting from the contradictory orders issued by different authorities.

next...

Test of coding for a meeting between the player and a mobile checkpoint. Jean Cristofol and Cédric Parizot, October 2015. Play online:

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/twine/MobileCheckpoint.html

18 Nevertheless, as with any visual language, this coding is not univocal. First, it is intersubjective, in the sense that it brings together the different subjectivities of his designers. Our collaborative process resulted in the assemblage of a variety of visions and ways to stage this meeting between the player and guards at mobile checkpoints. The initial series of dialogues in Twine represent a synthesis of my propositions and Jean’s. This scenario was then transformed by the game format set up by Douglas which he re-coded using Fungus, an open-source software that can be integrated into Unity. Through this operation, he gave the game rhythm, space, and an aesthetic that could not be achieved in the textual version. He also rewrote the dialogues in order to give them a format better adapted to English. One of our first decisions was to use English because we wanted the game to reach a wider audience, by making this choice we knew it would redefine the interactions in sharp contrast to what I observed on my ethnographic fieldwork.

It is hard to construct a critical discourse in the form of a polemical game, without falling into the trap of the large private and university institutions that dominate the video game industry.

Finally, we must mention the fact that the inclusion of external elements, such as animated characters, had a strong impact on the re-coding process. Given the material conditions in which we developed the game, we had no other choice but to design these characters using an open-source motion capture database provided online by Carnegie Mellon University. Because these images are based on recordings of American citizens, they bring a certain type of body language that is very different from what can be seen in the Israeli-Palestinian context. Ironically, this decision reminded us that, for material and financial reasons, it is hard to construct a critical discourse in the form of a polemical game, without falling into the trap of the large private and university institutions that dominate the video game industry. Even if the rules of interaction that I had defined in order to demonstrate the attitude of soldiers and police officers had not changed, the code staged them through dialogues and movements that displayed different content and representations. In this way, we were able to measure the limits of the theory of procedural rhetoric as defined by Ian Bogost (2007). His theory has been heavily criticized for its determinist and instrumental approach to code which only sees the player’s acts as a way of actualizing an argument already defined in the code (Sicart, 2011). We seek here to formulate an additional criticism of this theory by stressing the need to take into account the contingent and intersubjective nature of the process of modelizing knowledge and statements through the code. It is important to underscore the non-universality of representations portrayed by the animated game. In summary, not only does a video game accumulate and express heterogeneous meanings and content, but these contents are not understandable by everyone. Before even discussing their potential for communication, we must focus on their limitations for modelizing a statement.

next...

Animation test by Douglas Edric Stanley on Unity, 2015

c. From scientific explanation

to artistic and political questions

19 This being said, since autumn 2014 thanks to a new mediation operated by Jean, we began to envisage A Crossing Industry not anymore as simple documentary. Over several months we had been experiencing difficulties in making progress with the writing of dialogues and in developing the graphical interface, as the differences between my concerns relating to the documentary and Douglas’ concerns relating to esthetics prevented us advancing the project. As a solution, Jean suggested that we invent a fable which would allow us to develop a dynamic outline of the scenario and to refocus on the game’s poetical qualities.

Inspired by the Palestinian lawyer Raja Shehade’s autobiography, Palestinian Walks (2008), we decided not to use the figure of a Palestinian worker as the protagonist, but to have the player take on the role of a young Palestinian man wanting to go for a walk. Leaving a village near the wall of separation to the south of the West Bank, the player has to make his way past Israeli surveillance systems using passages set up and run by smugglers. His only objective: to walk and enjoy the countryside around his village, the Dead Sea and the Mediterranean.

By using this fable, we were able to articulate our approaches together, as the poetic detour brought by this fable radically challenged the conventional clichés relating to Palestinians: by having the player go for a walk, an activity with no specific or practical objective, the game avoids the trap of portraying the life and actions of Palestinians only in terms of their conflictual relationship with Israel or through the humanitarian discourse of victimization. The humanitarian narrative, while defending the rights of Palestinians, too often focuses only on their needs and difficulties in obtaining access to the job market, medical services, education and their own resources. As Ariel Handel (2015, p. 78) so appropriately stated in his description of Raja Shehade’s book, our game insists on the idea that Palestinians are, before all else, “… insisting on being a lively human being, living and experiencing life to the full, who is fighting against his flattening into a biological creature defined only by his medical, educational and agricultural needs.”

By using this fable, we were able to articulate our approaches together, as the poetic detour brought by this fable radically challenged the conventional clichés relating to Palestinians.

During spring 2015, Jean set up a writing workshop with a group of students, including Théo Goedert, Milena Walter, and Yohan Dumas, at the École supérieure d’art d’Aix-en-Provence. They contributed their ideas for nurturing and enriching this fable. In autumn 2015, during another week-long workshop, other students offered their input for these proposals. Gradually, we created a back-story, an individual personality and aspirations for a character we finally named Raja, as the first act for the narrative — an option we could not use in a traditional research documentary. A Crossing Industry had definitively shed its explicative and scientific approach and emerged as an artistic and political manifestation.

next...

Portion of the Separation Wall at Behtleem (West Bank).

Photograph by Cédric Parizot, 2009

Conclusion

20 Video game technology does not constitute a more effective medium for the modelization of research, nor does it contain any special ingredient for artistic creation. From a strictly anthropological point of view, video games do not allow us to achieve greater conceptualization or explanations. Similarly, given the impossibility of reducing the gaps between our two approaches, they do not really succeed in reconciling research and artistic creation.

On the other hand, by putting these disparities into perspective and working within their constraints, the process of developing games has challenged us at several levels. First, it gave me an opportunity to approach critically the devices of knowledge on which I usually rely. This approach was not just a rational process for me. By involving myself personally and directly in the programming process, I tested the limits of my own framework of representation. By engaging with video game technology and artistic practice, I was able to operate and experience the emotional process of decentering and distancing, which was similar to my experiences during my trips in and around the Israeli-Palestinian spaces (Parizot, 2012). Next, the restitution of the process of conceptualization for A Crossing Industry allowed me to introduce nuances into the video games’ rhetorical capacity. Given the contingent and intersubjective character of the modelization produced by code, the rhetoric produced by a game cannot be considered the result of an intentional and controlled process.

Finally, the interest in the interaction between ethnographic research, artistic practice and video game technology lies in the game’s offbeat discourse; a discourse emerging from the fable of a walker (flaneur) who challenges the clichés and narratives inherent in dominant discourse about Palestinians, as well as the often over-utilitarian aspect of serious games and scientific explanations. By attempting to document the conflict accurately and seriously, we in fact often avoid many of its most important aspects.

bibliography...

Bibliography

21 BOGOST, Ian, 2007, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games, Cambridge, London, MIT Press.

BOURRIAUD, Nicolas, 2002, Relational Aesthetics, Paris, Les presses du réel.

B’TSELEM, 2004, Forbidden Roads: Israel’s Discriminatory Road Regime in the West Bank, Août, [Online] consulted 17 March 2016, URL: https://www.btselem.org/download/200408_forbidden_roads_eng.pdf

CAILLET, Aline, 2014, Dispositifs critiques. Le documentaire, du cinéma aux arts visuels, Rennes, PUR.

CLEGER, Osvaldo, 2015, “Procedural Rhetoric and Undocumented Migrants: Playing the Debate over Immigration Reform”, Digital Culture and Education 7(1), p. 19-39, [Online] consulted 16 March 2016, http://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/cleger.pdf

DANON, Eyal and EILAT, Galit, 2006, Forbidden Games, Maarav [Online] placed online 28 December 2006, consulted 10 March 2016, URL: http://www.maarav.org.il/archive/classes/PUItem4e99.html?lang=ENG&id=869

DE CERTEAU, Michel, 1990, L’invention du quotidien, Paris, Gallimard.

DEGARROD, Lydia, N., 2013, “Making the unfamiliar personal: arts-based ethnographies as public-engaged ethnographies”, Qualitative Research, 13, no. 4, p. 402-13.

FLANAGAN, Mary, 2009, Critical Play: Radical Game Design, Cambridge, London, MIT Press.

FOURMENTRAUX, Jean-Paul, 2010, « Le concept de dispositif à l’épreuve du net-art », in Violaine APPEL, Hélène BOULANGER, and Luc MASSOU (eds), Les dispositifs d’information et de communication : concepts, usages et objets, Paris, de Boeck, p 137-47.

FRASCA, Gonzalo, 2003, “Simulation versus Narrative”, in MJP Wolf, B. Perron (eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader, New York, Routledge, p. 221-35.

GARCETTE, Arnaud, 2015, La filière oléicole au pied du mur, PhD thesis on the Arab and Muslim World, supervised by Cédric PARIZOT and Annie LAMANTHE, IREMAM, Aix-Marseille Université, December.

GATTET, Benjamin, 2014, The Stephen King of Fighters, Master HES-SO Design, Haute École d’Art et de Design, Geneva, supervised by Nicolas NOVA, January.

GONZALEZ, Cleotilde, SANER, Lelyn D., EISENBERG, Laurie Z., 2013, “Learning to Stand in the Other’s Shoes: A Computer Video Game Experience of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict”, Social Science Computer Review 31(2), p. 236-243.

GRANJON, Fabien and Christophe MAJIS, 2015, « Vers une ‘nouvelle anthropologie’ critique ? Jalons pour une épistémologie matérialiste des humanités numériques », Journal des anthropologues n°142-143, p. 281-303.

GUARDIAN, 2014, “Bomb Gaza game pulled from Google app store – video”, The Guardian, [Online] placed online 7 August 2014, consulted 17 March 2016, URL: http://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2014/aug/07/bomb-gaza-mobile-game-google-video-facebook-playftw-app

HANDEL, Ariel, 2009, “Where, Where to and When in the Occupied Territories? An Introduction to Geography of Disaster”, in M. Givoni, S. Hanafi, A. Ophir (eds.), The Power of Exclusive Inclusion, Boston, Zone Books, MIT Press, p. 179-222.

HANDEL, Ariel, 2015, “What are we talking about when we talk about “Geographies of Occupation”?”, in LATTE ABDALLAH, Stéphanie and Cédric PARIZOT, Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall: Spaces of Separation and Occupation, London, Ashgate, p. 70-86.

HÖGLUND, Johan, 2008, “Electronic Empire: Orientalism Revisited in the Military Shooter”, Game Studies 8 (1) [Online] consulted 17 March 2016, URL: http://gamestudies.org/0801/articles/hoeglund

HOLMES, Brian, 2007, « Géographie différentielle. B-Zone : devenir-Europe et au-delà », Multitudes 2007/1 (no 28), p. 112-113. JPPI (Jewish People Policy Institute), 2015, “Policy Opportunities for Video Games and Interactive Entertainment”, in JPPI (ed.), Annual Assessment 2014-2015, [Online] consulted 17 March 2016, URL: http://jppi.org.il/uploads/JPPI_2014-2015_Annual_Assessment_English-Policy_Opportunities_for_Video_Games_and_Interactive_Entertainment.pdf

KEE, Kevin, 2011, “Computerized History Games: Narrative Options”, Simulation Gaming 42 (4), p. 423-440.

LATTE ABDALLAH, Stéphanie and Cédric PARIZOT (eds), 2015, Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall: Spaces of Separation and Occupation, London, Ashgate, URL: http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/9781472448880

MARINESCU-NENCIU, Alina Petra, 2015, “Collaborative learning through art games”, Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology, Volume 6, Number 1, Summer, [Online], consulted 17 March 2016, URL: http://compaso.eu/wpd/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Compaso2015-61-Marinescu-Nenciu.pdf

NEVILLE, David O. and SHELTON, Brett E., 2010, “Literary and historical 3DDigital game-based learning: Design guidelines”, Simulation and Gaming 41(4), p. 607-629.

PAILLOT, Frédéric, 2014, « Le conflit israélo-palestinien en jeux vidéo : une vieille histoire », Logithèque, [Online] uploaded 5 August 2014, consulted 16 March 2016, URL : http://www.logitheque.com/articles/le_conflit_israelo_palestinien_en_jeux_video_une_vieille_histoire_690.htm

PARIZOT, Cédric, 2012, “Moving fieldwork: Ethnographic experiences in the Israeli-Palestinian space”, in HAZAN, Haim and Esther HERTZOG (eds), Serendipity in Anthropological Research, The Nomadic Turn, London, Ashgate. URL: http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/52/10/51/PDF/AFFECT_TO_AFFECT-c.pdf

PARIZOT, Cédric, 2014, “An Undocumented Economy of Control”, in Lisa ANTEBY, Virginie BABY COLLIN, Sylvie MAZZELLA, Stéphane MOURLANE, Cédric PARIZOT, Céline REGNARD and Pierre SINTÈS (eds), Borders, Mobility and Migration : Perspectives from the Mediterranean, 19th-21st century, Brussels, Berne, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Vienna, PIE Peter Lang, p. 93-112. URL: http://halshs.archivesouvertes.fr/docs/00/73/63/29/PDF/An_Undocumented_border_economy.pdf

PARIZOT, Cédric and Douglas Edric STANLEY, 2014, “A Crossing Industry” Obs/IN #3 – En-Jeux [vidéo] des images, p. 112-119.

PEDERSON, Claudia Costa, 2010, “Trauma and Agitation: Video Games in a Time of War”, Afterimage 38 (2), September-October, [Online], consulted 17 March 2016, URL: http://vsw.org/afterimage/issues/afterimage-vol-38-no-2/

RUFAT, Samuel and Hovig TER MINASSIAN, 2012, “Video games and urban simulation: new tools or new tricks?”, Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography, Placed online, 19 October, consulted 4 January 2016. URL: http://cybergeo.revues.org/25561

SHEHADEH, Raja, 2008, Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape, London, Profile Books.

SCHNEIDER, Arnd and Christopher WRIGHT, 2006, Contemporary Art and Anthropology, Oxford, New York, Berg.

SCHNEIDER, Arnd, 2012, “Anthropology and Art”, in Richard FARDON, Olivia HARRIS, Trevor H. J. MARCHAND, Mark NUTTALL, Cris SHORE, Veronica STRANG, Richard A. WILSON (eds), The Sage Handbook of Social Anthropology, London, Sage. SICART, Miguel, 2016, “Against procedurality”, Game Studies 11 (3), December, [Online], consulted 17 March 2016, http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap

SQUIRE, Kurt, 2004, Replaying History: Learning World History through Playing Civilization III, PhD thesis, Instructional Systems Technology Department, Indiana University.

ŠISLER, Vít, 2009, “Palestine in Pixels: The Holy Land, Arab-Israeli Conflict, and Reality Construction in Video Games”, Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 2, p. 275–292.

TAWIL SOURI, Helga, 2007, “The political battlefield of pro-Arab video games on Palestinian screens”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 27, Number 3, p. 536-551.

TER MINASSIAN Hovig, RUFAT Samuel, 2008, « Et si les jeux vidéo servaient à comprendre la géographie ? », Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography. Placed online 27 March 2008, consulted 4 January 2016. URL: http://cybergeo.revues.org/17502

TRICLOT, Mathieu, 2011, Philosophie des jeux vidéo, Paris, Zones. UCLA (University of California Los Angeles), 2016, « Professor creates video games that redefine art», ScienceDaily, [Online] placed online 2 February 2016, consulted 16 March 2016, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/02/160202192423.htm

UNSWORTH, John, 2003, “The humanist: “Dances with wolves” or “Bowls alone”?” http://www.arl.org/storage/documents/publications/scholarly-tribes-unsworth-17oct03.pdf Consulted 4 January 2016.

YARON, Oded, 2014, “Gazans 'liberate Palestine' in New Computer Game”, Haaretz, [Online] placed online 30 October 2014, consulted 17 March 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.623363

notes...

Notes

22 1. Institut de recherches et d’études sur le Monde arabe et musulman (Iremam), UMR 7310, AMU/CNRS, Aix-Marseille Univ, IEP, CNRS-IREMAM, F 13000, Aix-en-Provence, France

2. École supérieure d’art d’Aix-en-Provence, 5 rue Émile Tavan, 13100, Aix-en-Provence.

3. Yohan Dumas, Benoit Espinola, Tristan Fraipont, Émilie Gervais, Théo Goedert, Mathieu Gonella, Martin Greffe, Bastine Hudé, Thomas Molles, Milena Walter.

4. This does not mean that we endorse the determinist approach of proceduralism. As Sicart (2011) underscores, the main error of proceduralists is to suggest that “the rules constitute the procedural argumentation of the game, and play is just an actualization of that process”. On the contrary, for us, our experiment is a constitutive element in these games (Triclot, 2011).

5. For Jean-Paul Fourmentraux, the term ‘device’ or ‘apparatus’(dispositif) is useful for stressing the “performative character of these devices (dispositifs) which opens up new opportunities for games and for negotiation, by underscoring their capacity to (re)configure actors and their practices” (2010, p. 137).

6. In Dispositifs critiques, Aline Caillet shows how the integration of new processes of effectuation (detour via fiction, recourse to performative methods, narration, and experimental approaches) in documentary film practices allows us to rethink critically how we access and construct reality.

7. “While the term ‘tropism’ is a good expression for describing the need or desire to turn towards something different or an exterior discipline, the notion of reflectivity indicates the critical return at the point of departure that seeks to transform the initial discipline, break out of its boundaries, and open up new possibilities of expression, analysis, cooperation and commitment within it. This two-way circulation, or transformative spiral, is what we can call extra-disciplinary.” See also the article by Anna Guilló in this issue.

8. Games created during the 1990s and 2000s tend to focus on the Israeli-Arab wars, in which Israel was opposed by its Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian and Jordanian neighbours: for example, flight simulators such as Israeli Air Force (Electronic Arts, 1998) and Wings over Israel: Strike Fighters 2 (Third Wire Production, 2008). In these, the player carries out missions and air raids in Israel’s opponents in 1967, 1973 and 1982. Others focus on earlier periods: e.g. HaHalutzim (The Pioneers) (FixinGames, 2016) in which the player learns about the life of first Jewish migrants arriving in Palestine in 1882

(https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=air.maingame7v2).

10. “Boycott, divestment and sanctions” is an international campaign calling for the use of economic, academic, cultural and political pressure on Israel in order to bring an end to the occupation and colonization of Palestine and ensure equal rights for Palestinian citizens in Israel and respect for the right of return for Palestinian refugees.

11. The game can be seen on the Israeli Army’s blog and can be downloaded via this link: https://www.idfblog.com/idf-ranks-game/#

12. Portable antitank grenade launcher, made in Russia.

14. http://gisha.org/about/about-gisha

15. I refer here to Michel de Certeau’s differentiation between strategy and tactics (de Certeau, 1990).

16. According to John Unsworth (2003, quoted by Granjon and Majis, 2015), “in the cooperative model, the individual produced knowledge which refers to and draws upon the work of other individuals; in the collaborative work, each person works in conjunction with the others, producing conjointly the knowledge that cannot be attributed to a single author”.

17. For a presentation of recently developed games on the theme of borders, see Cleger, 2015.

18. It was screened during the festival organized by the magazine Internazionale in October 2014.

19. In order to reinforce controls, through fixed checkpoints and roadblocks, over the movement of Palestinians, the Israelis introduced more and more mobile checkpoints on major roads. Totally arbitrary, set up whenever the soldiers or police officers decide, controls become increasingly unpredictable. In 2014 and 2015, the army set up, on average, 300 to 450 mobile checkpoints per month on the roads in the West Bank (B’Tselem, 2015, http://www.btselem.org/freedom_of_movement/checkpoints_and_forbidden_roads, consulted on 14 April 2016). Given these obstacles, it is now very difficult for Palestinians to know exactly how long any journey from one place to another may take.

20. Cf. http://fungusgames.com or http://github.com/FungusGames/Fungus

21. CMU Graphics Lab Motion Capture Database, cf. http://mocap.cs.cmu.edu

Remerciements...

Acknowledgements

23 We wish to thank the students of the École d’Art d’Aix-en-Provence who participated in the initial development phases of this video game. In addition, we express our immense gratitude to our colleagues who, by offering advice, listening and reading, contributed to the writing of this article, and to the production of the first drafts for A Crossing Industry: Anne-Laure Amilhat-Szary, Jean Cristofol, Aurélia Dusserre, Anna Guilló and Sabine Partouche. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers who evaluated the first versions of this article.

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/01-Parizot-Stanley-research-art-and-video-games-ethnography-of-an-interdisciplinary-exploration.pdf