antiAtlas Journal #2 - 2017

Fiction AND BORDER

Jean Cristofol

Jean Cristofol teaches philosophy and epistemology at the Aix-en-Provence School of Art (ESAAix). He is a member of the antiAtlas Journal’s editorial board and coordinator of the antiAtlas of Borders. He is a member of the PRISM laboratory (AMU-CNRS).

Keywords: fiction, border, hegemony, system of visibility, art–science relationship, representation, aesthetics, media, space, territory

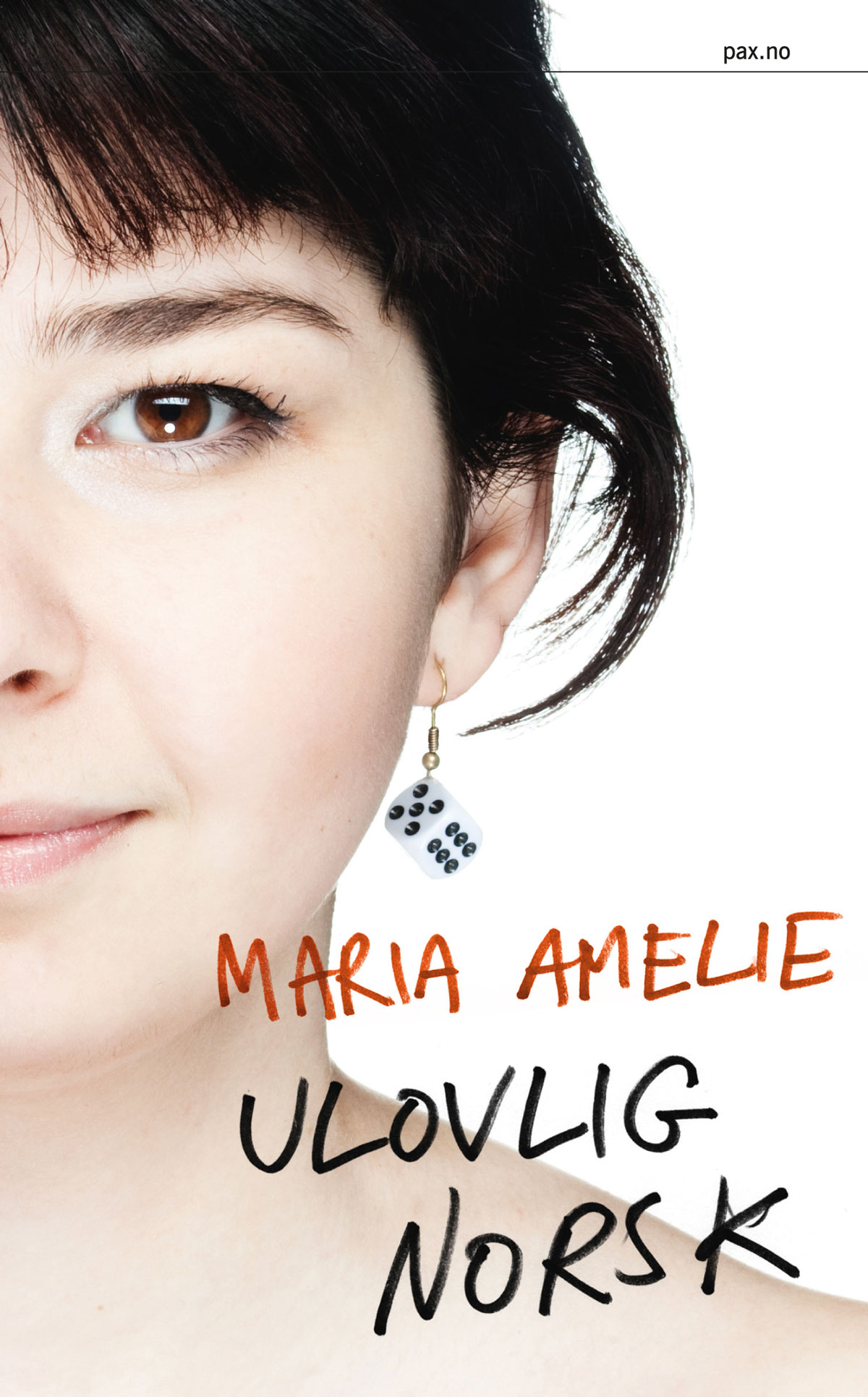

A Hungaro-Slovak border post. Photograph © Stéphane Rosière 2011

To quote this paper: Cristofol, Jean, "Fiction and border", published on December 10th, 2017, in antiAtlas Journal 02 | 2017, online, URL : https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/anti-atlas/02-fiction-and-border, last consultation on date

I. Fiction as a process and a strategy

1 Fiction’s relationship to the border is a topic that antiAtlas has pursued in its investigations since our collective work first started. In June 2013, we already organised a seminar entitled “Fictions de frontières” (Border Fictions) at the Institute for Advanced Study of Aix-Marseille University (IMéRA). Fiction and the border, border fictions: In the “distant proximity” between these two titles, one quickly senses that something continues to be sought, that an uncertainty remains. This uncertainty is part of the thinking itself and clearly relates to both of these terms. There is something else there, beyond a vagueness or a fumbling – it is not simply a question of wavering about terminology – that a rigorous and meticulous effort might dispel once and for all. It is not a question of considering how what is usually called fiction – in films or in literature – can choose the border as an element of its decor or one of its plot devices. Fiction will not be apprehended (except at the margins) as a genre, or as a category for stories, a form of imaginary narration as opposed to what might come from a description of reality. By going about it in a negative way, in other words, by clearly saying what is not at stake here, it will quickly become clear what this is. It is not a question of considering how what is usually called fiction – in films or in literature – can choose the border as an element of its decor or one of its plot devices. Fiction will not be apprehended (except at the margins) as a genre, or as a category for stories, a form of imaginary narration as opposed to what might come from a description of reality. This kind of use, strongly supported by classifications in the cultural industries, does not take into consideration what fiction is if it is considered not as a type of object but as a process and a modality of writing or of the production of representations. Documentaries and scientific products, however objective or factual they might aspire to be, inevitably carry with them or are steeped in fiction (Caillet 2014; Clifford and Marcus 1986). Describing reality requires a construction resting on selections that make it possible to highlight one aspect or another while minimising others. These descriptions occur in forms (films, articles, monographs, maps etc.) that involve every one of the forms of scientific writing and expression. Thus, the discourses of documentary or scientific objectivity mobilise rhetoric and formal and aesthetic choices intended to produce an effect of reality – and it should be recognised that this is also what traditional “fiction” does, albeit very differently and with another goal in mind. Poetic or artistic activities cannot be reduced to free subjective expression or imaginary construction, and the work of objectifying the scientific process involves the mobilisation of rules and norms that contribute to constructing reality as a representation and define the perspective as a way of perceiving and judging. next....

II Fiction as displacement

2 However, this does not mean that fiction fades into the indistinguishable totality of experience. Fiction is characterised by a certain momentum in how forms, situations and meanings are generated. Simply put, to reduce fiction to the world of imagination is to accept in advance a sort of ontological break between two levels and two types of reality –one would be given outside ourselves in the objectivity of a distance we confront, and the other would rise up from our internal activity, the free activity of our faculties of representation. Countering this binary pattern, we offer the idea that fiction is the specific strategy through which that which is uttered, told or depicted is given as a construction and an invitation to the free exercise of our capacity to perceive, to feel and to reflect. Countering this binary pattern, we offer the idea that fiction is the specific strategy through which that which is uttered, told or depicted is given as a construction and an invitation to the free exercise of our capacity to perceive, to feel and to reflect. Fiction entails the production of a sort of gap or displacement that makes it possible to mobilise attention and to suspend this tendency towards immediate adhesion, without there being any distance, that governs the imperative to survive, adapt or integrate into a social group. The children’s game of “pretending” is already a game about and with reality and supposes both a protective distance from the created situation and an emotional and sensitive engagement with it, a testing of its own affects. From this perspective, one might consider that a perfectly fictitious and illusory world – one that would wholly appeal to us in a process of total emotional and behavioural integration – would be reduced to a form of reality every bit as objective as “real reality”, if indeed such an expression makes sense. After all, this is what the Platonic criticism of simulacra was already focused on. By contrast, fiction means introducing flaws, disruptions and stimulating incoherence in that which seems to be naturally given, while at the same time providing us with a point of view that enables us not only to endure them but to perceive and reflect them. The power of what has traditionally been called fiction inheres, from this perspective, on the one hand in the fact that it is declared as such, in other words, it presents itself as fiction and says what it is (the tale says it is a tale, the novel presents itself as a novel etc.), and on the other hand in the fact that it mobilises strategies whose aim is to shift our gaze, our point of view, to show us the world in a different way, to shift us or to decentre us and to reawaken our perception and understanding (Chklovski 2008). These two aspects complement each other, and their articulation is based on the convention according to which the reader, the viewer, the listener himself or herself takes this enjoyable action of welcoming the fiction, sliding into it and surrendering – at least momentarily – to this displacement. Thus, fiction is a means of transport – a constituent transport that sets in motion both what we can be and can experience as people immersed in this world. Because it is expressed as such, it produces effects of proximity and of distance that turn the experience into a field of possibilities. But all of this is well-established and part of a discussion that dates back to at least the time of Aristotle’s Poetics. The result is simply that fiction is not only a category of stories but rather stories that are but one of the possible forms that fictional production can take. They certainly make up one of its major forms of expression, but artists, whose work it is to invent and create situations that generate sensory experiences, are constantly proving that there is a multitude of these forms and that fiction is not only narrative but also perceptive and “experiential”. And from the moment they leave behind these frames reserved for the established exercise of fiction to work the open, common field of our collective experience (which constitutes a historical process that can be observed in movements like Fluxus, as well as land art, performance etc.), they disrupt the accepted, integrated, assimilated and naturalised fictions, which are no longer perceived as fictions, in order to examine how they work. next...

III. Walls and Flows

3In a famous text, Paul Ricœur defends the idea that ideology and utopia are the competing and complementary expressions of the social imaginary as a producer of stories and fictions (Ricœur 1986). Fredric Jameson takes up the same idea but in a different way (Jameson 2012): It might be necessary that we attempt to go farther and question the limits of what might be identified as a social “imaginary”, as opposed to the material part of its production. Thus, social reality carries with it a part of fiction as an element that constitutes and moulds it. Its economic dimension, as objective and formalisable as it might claim to be, is not necessarily without it, as shown by the abstract model of a market modelled on the basis of free and equal competition between the actors. Thus, to begin with the seemingly antagonistic figures of the wall and the flow was a way to broach the issue of fiction and borders head-on. From this angle, the issue of borders is a privileged field of study and experimentation that puts to the test and questions fiction as the generative principle of perceiving and representing social reality. There are several contributing aspects, and we will mention three of them. The first is the fact that borders today have become central media objects in the production of security and identity discourses, to the point where it is no longer possible to consider them independently of these ideological and political issues, with the latter contributing to redefining and transforming even their physical reality. The second insists on them, far from being simple blind obstacles, serving as tools to collect data and produce images. Therefore, not only are they the focus of stories and representations, but they produce them in abundance by categorising and filtering the populations that are on the move and by profiling individuals. The third is more general and more structural: For roughly the past four decades, the transformations of borders have revealed new forms of organising space and time, new modalities of what Henri Lefebvre has called “the production of space” and new ways of conceiving, perceiving and living it (Lefebvre 1981). Thus, to begin with the seemingly antagonistic figures of the wall and the flow was a way to broach the issue of fiction and borders head-on. It is incontrovertibly apparent that the figure of the wall haunts contemporary mutations of borders. This can be seen as the result of a communitarian or national process of reacting against globalisation (Amilhat-Szary 2012, Parizot 2015, Rosière and Jones 2011, Vallet 2014). It can also be thought of as the construction of a story, not unlike a security shift or a withdrawal, whose political and media issues are dramatic drivers that accompany and justify an accelerated process of controlling individual behaviours on a global scale (Brown 2009, Ritaine 2012). It can be understood within the context of the evolution of borders in a world where different financial, commercial, linguistic and cultural, scientific and technical and, lastly, demographic and political flows generate dissociated and relatively autonomous spatiotemporalities, so that the economic globalisation becomes compatible with a spatial segregation of human mobility (Shamir 2005, Mezzadra and Neilson 2013). Beyond that, it becomes the means and the expression of a discrimination not only between national or ethnic groups but between categories of individuals whose value, including and perhaps first and foremost their economic value, is expressed through the type of mobility and access to freedom of movement (Parizot et al. 2014, Ritaine 2012). In a way, all these points of view lead to the complexity of a process of which the geographer Stéphane Rosière tries to take stock in an article that he titles, “The international borders between materialisation and dematerialisation”. He plays on the ambiguity of these two terms that simultaneously oppose and nourish each other but respond to the broader principle of a “teichopolitics” (Rosière and Jones 2011) considered as a contemporary expression of the Foucaldian concept of biopolitics. What is invented, what is told and unfolds there, is a new relationship with space and, behind it, a new ethic of relationships with the other, between abstract universality, the systemic organisation of control and surveillance, and widespread segregation. next...

A Hungaro-Slovak border post. Photograph Stéphane Rosière 2011, paper by Stéphane Rosière

IV. Liquid Traces

4Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani’s article, “Drifting Images, Liquid Traces: Disrupting the aesthetic regime of the EU’s maritime frontier”, is an extension of this thinking but leads us to dive into a space that is supposedly open, smooth and without any visible demarcation, the ocean’s liquid, seemingly ahistorical expanse – in this case, of the Mediterranean Sea. We know the tragedy of the migrants seeking to enter Europe on rickety vessels. We know that the Mediterranean has become an invisible cemetery. But we also know that images of overcrowded boats strengthen the perception of an uncontrollable invasion. It is precisely this “spectacularisation of the border” that the authors criticise by revealing the mechanism through which the media have decontextualised images and removed the circumstances that give them meaning can become abstract expressions of a political construction nourished by a fear of the other. It is precisely this “spectacularisation of the border” that the authors criticise by revealing the mechanism through which the media have decontextualised images and removed the circumstances that give them meaning can become abstract expressions of a political construction nourished by a fear of the other. Using the example of the “left-to-die boat” as a point of departure, which they utilised to make a remarkable video, Liquid Traces – The Left-to-Die Boat Case, they show with great precision how a process of reversing the techniques of documentation and investigation, usually in the service of the police or state justice, can be put in place to recontextualise the images, reconstruct the events they have witnessed and redraw the situations that give them meaning for the benefit of those who suffer from institutional violence. This article is part of the work by the Forensic Architecture collective and illustrates the group’s approach. It considers not only the images, their roles and their uses but also the act of photography itself. It compellingly illustrates this evolution that turns the illegible surface of the sea into a space defined and structured by remote sensing and data processing devices, which leads the authors to write: “Emerging at the intersection of electromagnetic and physical waves, what we see here is not simply a new representation of the ocean, but a new ocean altogether, one simultaneously composed of matter and media.” Of course, this is not only true of the sea but has to be generalised as one of the fundamental features of the new forms of territoriality. Territories are not only objects of representation – for example, cartographic representation. For a long time, maps have helped to define and establish them as continuous and homogeneous spatial units (Anderson 1996). But now, observation and information capturing systems do not only contribute to redefining and redrawing them – they also confer a new mode of existence on them that is of both a physical and a media nature, simultaneously spatial and informational.

next...

Left: Reconnaissance picture of the “left-to-die boat” taken by a French patrol aircraft on 27 March 2011.

V. The emergence of the self in writing

5Johan Schimanski also examines the issues of visibility and the line of demarcation between the visible and the invisible. He does so by approaching the construction of fiction in a completely different way. Here, it is essentially about literature and, more specifically, about the way in which literature can become the space where a word emerges and writing works to turn back the spectacularisation of the border and its mechanical effect of de-individualising and anonymising the migrants, refugees and undocumented individuals by recognising writing, a singular, personal story, a story conveyed by voice, inscribed in the body and affirmed with a face. Thus, the border is no longer understood only as a territorial delimitation but also as the object and the source of representations imbued with aesthetic and political issues. Drawing on Jacques Rancière’s concept of the distribution of the sensible (Rancière 2013), Schimanski clearly shows how much the issue of visibility involves aesthetics in the realm of policy by producing and establishing a point of view that reveals or, on the contrary, destroys part of reality. It is an approach that no longer assigns aesthetics to the exercising of a disinterested judgment but conceives it as a confrontational space dealing with the lines of separation between what is perceived and what is disappearing, what is worth and what loses its value, along with its capacity to make sense and produce emotion. It is an approach that no longer assigns aesthetics to the exercising of a disinterested judgment but conceives it as a confrontational space dealing with the lines of separation between what is perceived and what is disappearing, what is worth and what loses its value, along with its capacity to make sense and produce emotion. It is the space of the construction of hegemonic or alternative, oppressive or liberating forms, not only of the perception of the world but also of the way in which this perception is constructed, disseminated and accepted, identified and internalised. Johan Schimanski recalls the richness of the French term “partage”, which simultaneously means division, distribution and shared experience, to better reveal the contradictions and the complexities of approaches that can erase the collective reality because they are individual, can facilitate surveillance because they put themselves on display and can also be a way to leave behind those who are repressed because they allow whoever is writing to be integrated and valued. By focusing his analysis on a book written by a migrant, Maria Amélie, who completed the process of integrating into Norwegian society by publishing a book markedly and ironically titled Takk (“Thank you”), while supplying his presentation with examples that often play as counterpoints, Schimanski allows us to follow the knots of these tensions from up close. He does so without reducing the terms of oppositions or of relations of dominance, between north and south, legal and clandestine, man and woman. Here, the gap, the separation, the subjection to the frame of a point of view, as well as the crossing, the transparency and the lucidity play with the same figure of the mirror, the glass, the lens of the objective or window. Fiction is no longer on one side or the other; it is the strategic space in which these contradictions are challenged, pitched against each other, offered to raise awareness or, on the contrary, integrated into the collective and naturalised consciousness. next...

The cover of Maria Amelie's Ulovlig norsk (2010) with half portrait image of Amelie symbolizing a transition from invisibility to visibility. Reproduced by permission of the publishers. Paper by Johan Shimanski.

VI. Recording the border

6 In a way, Elena Biserna’s thinking reflects some of the markers found in Johan Schimanski’s text: the game of opposing movement with closure, fluidity with spatial segmentation, for example, and from there a desire to question and work on the notion of borderscape (Brambilla 2015) as a setting in motion of the border, or the importance of constructing forms as a process of building a fictional retreat. But it is no longer a question of literature; it is a question of recording sound, producing listening systems, investigating acoustic phenomena in an artistic way. And this change in perspective leads us to consider in a completely different way what was engaged in the narrative detour of the problems in writing, by investing one part of the materiality of borders to test it through experience and to tip it over into the sensitive relationship. In a remarkably precise build-up that is richly documented, including with moments of listening that prolong and scramble the reading, the author provides us with a number of examples of artistic approaches that all start with the practice of “recording (at) the border”. The complexity sought by having the two formulations together leads us straight to the heart of the presentation: Sound reality is different from visual reality; it is more capable of catching the displacements, the circulations and the fluctuations of the co-existing realities. The border, silent on its own, can become a capacitor of sound events. The classical representations we have of it are determined by the logic of visual perception. But while the border can be an interruption of the movement of bodies, and while it can rise like a screen that partitions our view, it is also a membrane that vibrates and is filled with sounds and voices. The sound space is not so easily bound. This is because sound is not a thing – it is a vibration, a relational reality that disturbs the play of classical oppositions between sides that are too easily substantialised: the subject and the object, the interior and the outside, oneself and the world, objectivity and affectivity. Elena Biserna strives to show us that “[s]ound, the mobile and wandering is par excellence, constantly transgresses limits, crosses barriers and calls monolithic identities into question”. But this critical potentiality can only be effective in the development of a process of constructing, composing or at least organising and articulating listening situations. Elena Biserna strives to show us that “[s]ound, the mobile and wandering is par excellence, constantly transgresses limits, crosses barriers and calls monolithic identities into question”. But this critical potentiality can only be effective in the development of a process of constructing, composing or at least organising and articulating listening situations. It is not a question of merely capturing atmospheres; it is necessary to arrange them in such a way that their potential meanings are revealed and they come to life through an approach that can restore the value of their experience. next...

Jacob Kirkegaard, Through the Wall, ARoS Art Museum, Aarhus, Danemark, 2017. Photograph Jacob Kirkegaard, paper by Elena Biserna.

VII. The artist as a strategist

7As an artist and because of the way in which he conceives and develops his own work, Raafat Majzoub offers us a contribution that is both dense and exciting with respect to the question of fiction. The strength of this text lies in its frontal approach to the subject, not as a pretext for an academic discussion but as both a theoretical and a practical issue at the heart of his own approach. In this way, he develops his thinking in a way that is based directly on his own work, some of whose elements he brings up and might seem disjointed because of the diversity of their forms, their mediums, their ways of presenting themselves to the public, but which reveal themselves – or are shown to us – as parts of a system of intervention in a broader social and cultural process. This leads him to call into question the illusion of the author having a position of externality or predomination. Here, it is not a question of describing a reality, nor even of testifying to a lived experience, but of conceiving the position of the artist like that of an actor in a world that obviously goes beyond him, but whose possible forms he nevertheless helps to define. It is from his real situation as an actor and initiator of poetic and political situations in the society in which he lives that Raafat Majzoub builds his thinking. This thought only fully exists in its two moments, theoretical and practical, plastic and critical, in such a way that this text is also a “theoretical fiction” and that it participates just as much in the production of that which it reports on. It is from his real situation as an actor and initiator of poetic and political situations in the society in which he lives that Raafat Mazjoub builds his thinking. This thought only fully exists in its two moments, theoretical and practical, plastic and critical, in such a way that this text is also a “theoretical fiction” and that it participates just as much in the production of that which it reports on. Let’s say that fiction is no longer an object here but the core of an approach that claims to contribute to the very reality in which it unfolds. It is therefore easy to understand that, if there is a fundamental question about the relations between reality and fiction, it is not on the level of an opposition between two essentially opposing and exclusive categories but between that which is part of a world that is no longer questioned and that one accepts as a given and the capacity to produce a force and a desire to question. From this perspective, the opposition he offers us between “active fictions” and “dormant fictions” is itself a formidable source of questioning. In a certain way, we can find something of the balance that we mentioned above between ideology and utopia but without that which these two terms maintain of an essentialist bipolarity. What defines this opposition is a strategic and fluctuating space, a field of power relations, in which the discursive elaborations, as well as the configurations of images, beliefs and ways of seeing and feeling, are elements outlining relationships of dominance and the acceptance of dominance or resistance. Here, we find ourselves in a much more fluid and, admittedly, disturbing way of thinking because it does not really offer us a space where to rest or take refuge. By contrast, there are issues and strategies and a certain way of mobilising each of them, starting with their own dreams and desires. There is also a very pragmatic way of looking for the conditions under which fictions can be embodied in institutions and social organisations, borrow channels of circulation and ways of recognition to acquire collective legitimacy, which is reminiscent of Gramsci and his concept of hegemony (Gramsci 1996). Raafat Majzoub asserts a practice of “writing as architecture”, which he proposes as the model for arranging constructive and critical fictions. They stand at two removes: from the architect’s drawing in relation to the concrete realisation and from the freedom of the invention in relation to the constraints of a reality where the dominant forces work to eliminate what might be threatening to them. next...

Left: The Beach House, image from the movie, Roy Dib, co-author Rafaat Mazjoub, 2016

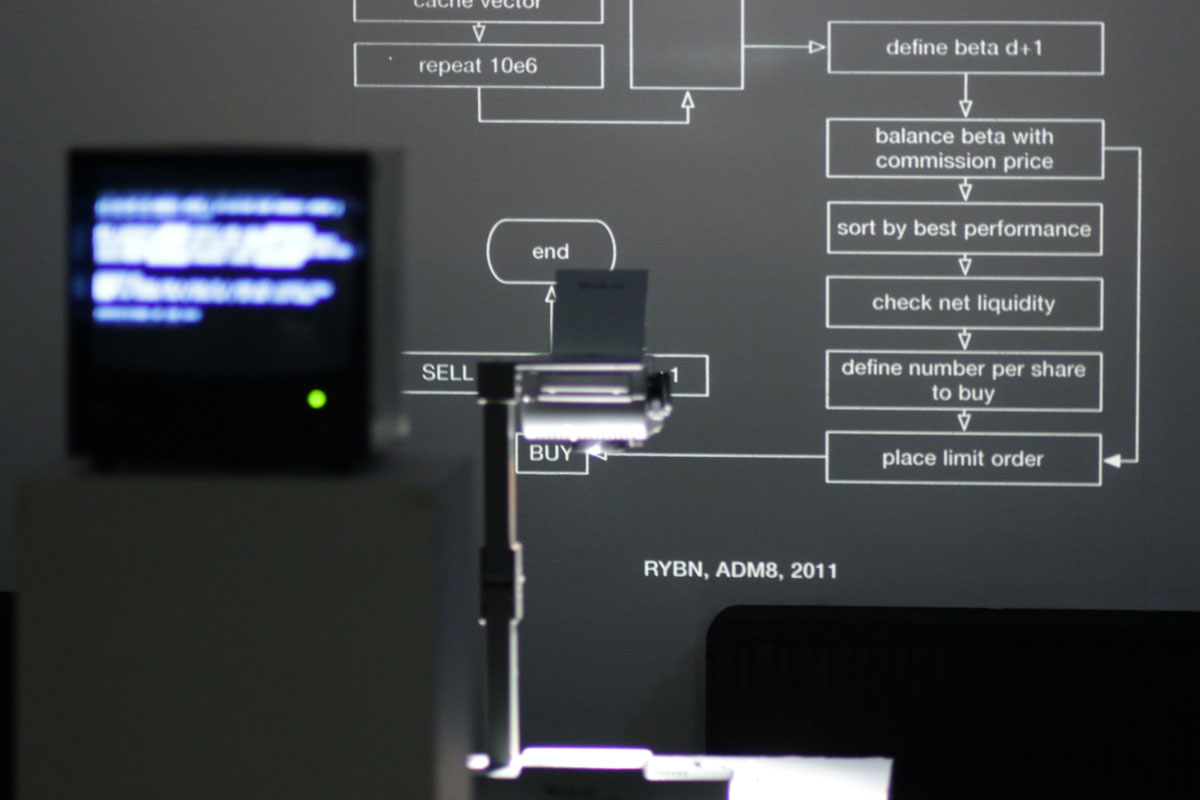

VIII. The mathematisation of the border

8At first sight, one might think that Thomas Cantens’s article is the exact opposite of such a consideration of fiction as a strategic space. An anthropologist, customs officer and director of the World Customs Organization’s Research Unit, he finds himself in an ideal position to study the reality of the workings of cross-border trade. And the issue that preoccupies him, the mathematisation of the border, seems to place us at a radical remove from fiction. Obviously, we will see that it is not so simple. Here again, albeit in a completely different way, the question arises of the relationship between the forms of language, the reality within and the power relationships that play out there. This does not mean settling for modelling and calculation procedures being reduced to simple ideological constructions. Thomas Cantens adopts another perspective, by considering the historical process of producing, collecting and quantifying data as part of an evolution of the forms of knowledge as power relations that go far beyond the imposition of an economic model of capitalism or the neoliberal ideology. To state it in simpler terms, it is a question of shining a light on the evolution of the commercial relations and their quantification as a complex development whose political and ideological dimension is but a single aspect. Thomas Cantens does not discount the critical analyses that have been developed both on the question of forms of control and surveillance and the problem of big data and how they are treated. But in his view, these models also reflect a transformation of the reality of the border issues, their displacement from the scene of territorial policies to those of the trade and circulation policies between states. In his eyes, there is a link between extending the quantification of data and extending the exercise of state policies beyond territorial limits, in the direction of the issue of the international organisation of flows. Therefore, what Cantens calls “governance by numbers” is not only a pathogenic construction that should be fought as such; it is part of the very reality in which we live. When he writes that the “border is a fiction with very real effects” and that, as maps used to be, the “mathematisation of the border is part of this very human effort to make borders legible”, he highlights the link between the reality of the borders and the forms in which they have been operational and thus efficient. Therefore, what Cantens calls “governance by numbers” is not only a pathogenic construction that should be fought as such; it is part of the very reality in which we live. This leads him to propose a critical position in our relationship with the potentially unlimited extension of data and with their mathematical processing, beyond disobedience or regulation by the law, which consists in grasping the language of calculation in order to occupy the space of mathematisation itself as a form of exercising power: “Using the language of calculation does not mean that utilitarian thinking has to be adopted or that individuals have to surrender to calculation in order to change their behaviour. Using the language of calculation simply means recognising in the calculation a human practice that is not exclusively reserved for a form of government.” next...

ADM8, installation, 2011 - 2015, RYBN collective. Photograph Myriam Boyer

IX. Exploring the possible

9By proposing the approach of “adopting the language of calculation in order to challenge its results”, Thomas Cantens is not far from the approach of Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, and more generally of Forensic Architecture. All of them capitalise on the methods of scientific investigation in criminal matters to look for material elements that allow for the conditions of exercising violence to be restored to the authorities and their agents and to bring them to the field of public confrontation. But more generally, it always involves a practical field, as well as the languages and approach that develop there, to call into question the limits of the visible and the invisible, the legible and the illegible. A system of representation, whatever it is, can only account for part of reality by obscuring another. It is one of the oldest lessons of cartography and of the different projections that offer us varying representations of space, but it is also what the rules of perspective teach us. There is no such thing as total visibility, and there is no absolute transparency. Every time, there are more or less identifiable, more or less explicit and conscious ways of drawing the division between what is perceived and what is imperceptible, depending on the type of perspective that is imposed by the systems of representation or, on another scale, by the choices that govern the models of analysis or the production of representations. One of the challenges these constructions have is to appear credible, to gain our consent and our adherence. Thus, the operation of fiction consists in seizing the forms and the models and questioning them, confronting their limits, their dead ends and their uses, and thus, exploring their possibilities as much as their power of persuasion (Westphal 2007). There is no such thing as total visibility, and there is no absolute transparency. Every time, there are more or less identifiable, more or less explicit and conscious ways of drawing the division between what is perceived and what is imperceptible, depending on the type of perspective that is imposed by the systems of representation or, on another scale, by the choices that govern the models of analysis or the production of representations. In this regard, the same applies as to the photographer whom Vilém Flusser describes in his booklet on photography (Flusser 2000): The camera responds to a programme, but all the possibilities of this programme can only be discovered by the photographers handling the camera. Of course, it is still possible to continue using the camera according to the norms imposed by convention and to reproduce them. But the living part of the fictional activity does not entail repeating that which has already been established; it tends to explore what is possible. As Flusser writes (2000, 27): “Such activity can be compared to playing chess. Chess-players too pursue new possibilities in the program of chess, new moves. Just as they play with the camera. The camera is not a tool but a plaything, and a photographer is not a worker but a player: not Homo faber but Homo ludens. Yet photographers do not play with their plaything but against it. They creep into the camera in order to bring to light the tricks concealed within.” Jean Cristofol, 2017 next...

Bibliography

10 Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, 2012, « Murs et barrieres de securite : pourquoi demarquer les frontières dans un monde dematérialisé ? », in Ghorra-Gobin, Cynthia, Dictionnaire des mondialisations (2e édition augmentée), Paris, Colin, p. 447-451.

Anderson, Benedict, 1996 (1993), L'imaginaire national. Réflexions sur l'origine et l'essor du nationalisme, Paris, Éditions La Découverte.

Brambilla, Chiara, 2015, « Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept », Geopolitics, 20(1).

Brown, Wendy, 2009, Murs. Les murs de séparation et le déclin de la souveraineté étatique, Paris, Les prairies ordinaires.

Caillet, Aline, 2014, Dispositifs critiques : le documentaire, du cinéma aux arts visuels, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Chklovski, Victor, 2008 (1997), L'art comme procédé, Paris, Éditions Allia.

Clifford, James, Marcus, George E., 1996, Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Flusser, Vilém, 1996, Pour une philosophie de la photographie, Belval, Éditions Circé.

Fredric, Jameson, 2012, L’inconscient politique, Paris, Questions Théoriques.

Gramsci, Antonio, 1996, Cahiers de prison, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, Bibliothèque de philosophie.

Jameson, Fredric, 2012, L’inconscient politique, Paris, Éditions Questions Théoriques, Lefebvre, Henri, 2000, La production de l’espace, Paris, Éditions Anthropos.

Mezzadra, Sandro, Brett, Neilson, 2013, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor, Durham, NC-Londres, Duke University Press.

Parizot, Cédric, 2016, « Murs », in Albera, Dionigi, Crivello, Maryline, Tozy, Mohamed, Dictionnaire de la Méditerranée, Arles, Actes Sud.

Parizot, Cédric, Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, Popescu, Gabriel, Arvers, Isabelle, Cantens, Thomas, Cristofol, Jean, Mai, Nicola, Moll, Joana, Vion, Antoine, 2014, « The antiAtlas of Borders, A Manifesto », Journal of Borderlands Studies, Vol. 29, Issue 4, p. 503-512.

Rancière, Jacques, 2000, Le partage du sensible, Paris, La Fabrique-éditions.

Ricoeur, Paul, 1986, Du texte à l’action, Essais d’herméneutique, II, Paris, Éditions du Seuil.

Ritaine, Evelyne, 2012, « La Fabrique politique d’une frontière européenne en Méditerranée. Le “jeu du mistigri” entre les États et l’Union », Les Études du CERI, 186, juil.

[http://www.ceri-sciencespo.com/cerifr/publica/etude/etude.php]

Rosière, Stéphane, Jones, Reece, 2011, « Teichopolitics: Re-considering Globalisation through the Role of Walls and Fences », Geopolitics, 17, 1, p. 217-234.

Shamir, Ronen, 2005, « Without Borders? Notes on Globalization as a Mobility Regime », Sociological Theory, 23 (2005), p. 197-217.

Vallet, Elisabeth (dir.), 2007, Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity?, Londres, Routledge.

Westphal, Bertrand, 2007, La Géocritique. Réel, fiction, espace, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Paradoxe ».

Notes

1. http://www.antiatlas.net/fictions-de-frontieres, accessed 27 October 2017

2. One of the features of these movements and these practices is the transition from representation to action, in the museum or gallery exit being spaces reserved as areas shared every day for common, social use.

3. Vimeo link, https://vimeo.com/89790770, accessed 7 November 2017

4. http://www.forensic-architecture.org/, accessed 7 November 2017

5. “Therefore, fiction consists not in showing the invisible, but in showing the extent to which the invisibility of the visible is invisible”, Michel Foucault, “The thought from outside” in: Foucault / Blanchot: Maurice Blanchot: The Thought from Outside and Michel Foucault as I Imagine Him, translated by Brian Massumi, Zone Books, New York, 1987, p. 24.

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/02-Cristofol-introduction-fiction-and-border.pdf