antiAtlas Journal #5 – 2022

Struggles against the “deportation machine”: on the anarchist track

Clara Lecadet and William Walters

This article examines anarchist struggles against deportation in France, reconstructing their fragmented history. We highlight the idea of a “deportation machine” that these campaigns popularized, and ask how these movements expand the field of political action beyond the state, entangling airlines, airports, travel agents, and other commercial actors in the struggle against deportation.

Clara Lecadet is a researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research. She works on deportation policies, deportees’ grassroots movements in Africa and refugee camps.

William Walters teaches politics at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. His interests include security, secrecy, migration and governmentality.

We wish to thank Rosemary Masters for translating this text from French. We are also grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canada) who provided support for this research (grant # 435-2017-1008).

Keywords: antideportation activism, deportation machine, anarchism, sans-papiers

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportation"

Directed by William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Graphic design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

To quote this article: Lecadet, Clara and Walters, Williams, "Struggle against the "Deportation Machine": on the Anarchist Track" published on June 1st, 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL : www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-lecadet-walters-struggle-agains-the-deportation-machine-on-the-anarchist-track, last consultation on Date

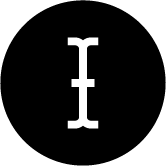

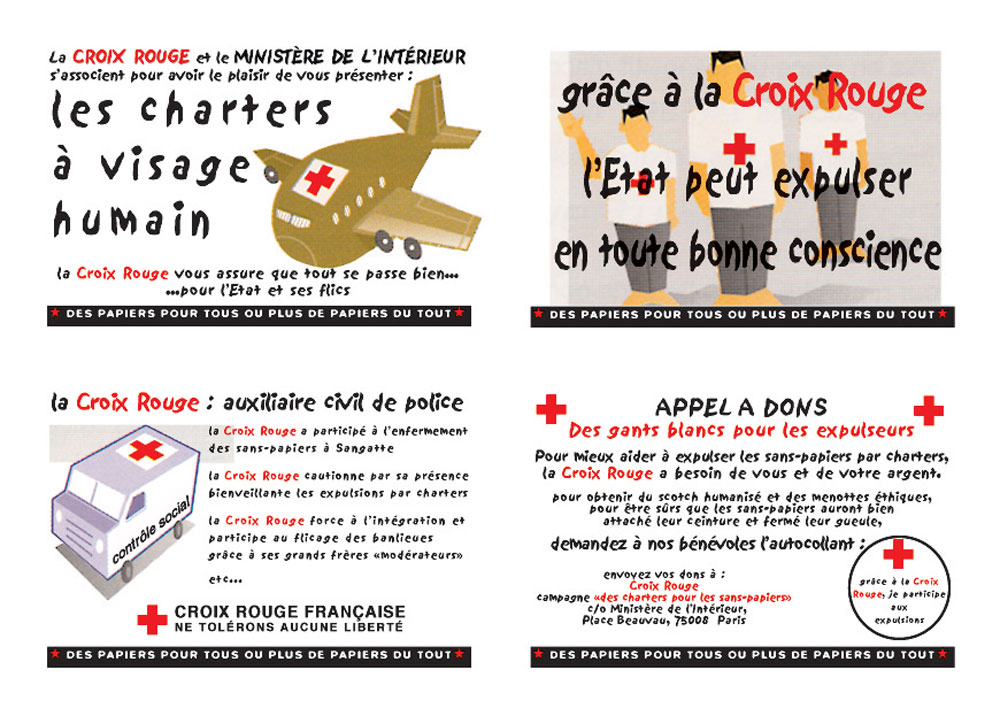

Collectif Anti-Expulsions, October 2003 (Excerpt), Source : pajol.eu.org

Why anarchist struggles against deportation matter

1 In this essay we call for closer attention to the political discourses, interpretive frames, and practices of struggle which certain anarchist groups and networks have brought to the realm of deportation. We focus specifically on anti-deportation activism in France, though certain resonances can no doubt be found in other European countries where political actors and movements have also drawn upon anarchist logics and tactics. While scholarship on social movements and political struggles around migration issues has greatly expanded in recent years, the ideas and practices of anarchist movements have been somewhat marginal to most of these studies. Researchers take far-right movements of anti-immigration very seriously whereas political anarchism has not received the same level of scholarly attention. Perhaps anarchism is regarded as a very fringe element and rather inconsequential. We offer two reasons for taking anarchism seriously as a force within migration activism and border struggles.

First, on sociological grounds, this move contributes to a richer account of the wider field of migration politics and solidarity movements. The argument for an “undisciplined” migration study that refuses to essentialize types of persons (e.g., “the immigrant”), and eschews the privileging of one particular axis of struggle (e.g., states versus migrants) has already been well made (Garelli and Tazzioli, 2013). This de-disciplining perspective engages migration politics as a heterogeneous field populated with many kinds of actors and struggles. We seek to strengthen such a perspective with this contribution. While anarchists might not be as ubiquitous as humanitarians across the migration field, or as visible as the social movements of the far right, a proper account of this field certainly requires they be recognized. One benefit of this move is to illuminate dynamics of struggle within this field. In particular we highlight the way in which anarchists become targets of police repression, which in turn creates the space for campaigns of solidarity and support with members facing arrest and punishment. In this way a focus on anarchism illustrates the iterative, looping, and centrifugal character of migration politics.

Rejecting the very principle of bordered citizenships and state territoriality

Second, we argue that anarchist movements are important because of the forms of knowledge and normativity as well as the tactics of direct action they have brought to the realm of deportation. It is a feature of many anarchist movements that they reject the state’s desire to differentiate between migrants with “status” and those without (Mudu and Chattopadhyay, 2016: 26). As the now famous slogan “No one is illegal” emphasizes, these movements call into question the very idea that humans, as such, can or should be categorized according to a logic of legality, and that such designations should circumscribe any right to move or right to reside (Nyers, 2010). As such, anarchism is important because it has opened space for the critique of deportation not on the grounds of compassion, human rights, administrative process or fairness, but on the basis of rejecting the very principle of bordered citizenships and state territoriality.

Anarchism is important not just for the normative space it opens up. It has provided analytical tools as well. For many decades studies in the governance of migration privileged the angle of institutions, policies and interest groups. While such approaches remain influential, recently there has been a broadening of perspective. Using concepts like assemblage, migration industry, disciplinary complex, borderscape and carceral geography, scholars have begun to look beyond the state, to explore the interconnection of state and non-state actors, and the role of commercial, technological and logistical factors in mediating power relations and political outcomes. We insist that this necessary and important move did not originate entirely academia. Some time before this “turn” within critical migration studies, we show that the move to explore political economies, industries and spaces beyond the state, and to foreground the actual practices and mechanisms by which migration control is effected, this was anticipated by anarchist praxis.

next...

2 In this paper we highlight how anarchists mobilized the idea of a “deportation machine”. Since the role of airlines, airports and travel agents figures very prominently in this concept, this focus on the deportation machine is particularly relevant to this collection on air deportation. Indeed, in these anarchist struggles we find a kind of hidden line in the genealogy of air deportation. For it is here that one sees an early and prescient attempt to name and theorize aviation infrastructure as a site of tactics and strategic intervention in antideportation struggles. In making this move, anarchist groups broadened the very terrain of struggle: commercial airline offices and travel agencies became targets of protest and disruption, just as the logos and the slogans of airlines became media of détournement and grammars of protest. At the same time, these movements also recognized the limitations of such a focus. Hence, anarchism can be treated in terms of “cramped space” (Walters and Lüthi, 2016), where political inventiveness takes shape in the confrontation with blockage, limitation, and impossibility.

Anarchist groups broadened the very terrain of struggle

The aim here is to try to establish the lexicon, political analysis and strategic action on which the anarchist collectives engaged in the struggle against deportation in the 1990s and 2000s. We will attempt to look back, not only at the chronology of these collectives in France, at the strategies and issues around which they were built and the tensions and criticism they came up against and which contributed to their dissolution, but also at how they contributed to an understanding, from the perspective of infrastructure and logistics, of the different workings of the “deportation machine”. The critical thought and political reflection which accompany direct action are part of the construction of an overall view of expulsion measures, and their political and economic provenance. We will then try to show that the development of collective movements in France and Europe in the 2000s consisted of reassigning the specific issue of the detention and expulsion of foreigners to the general theme of incarceration and the surveillance society. While collectives had initially concentrated on denouncing deportation by targeting airline companies above all and by inventing different kinds of action within airports, the 2000s were particularly marked by riots within detention centres and the protest movements which accompanied them on the outside. Anarchists also sought to reformulate the issues in these struggles; struggles which would no longer be exclusively based on immigrants, but on the proclamation of a shared condition in the grip of incarceration powers, deprivation and the surveillance society. And finally, we will reflect on the way in which the increasing judicialization of protest action and protest movements against deportations by air, and the classification of certain actions by anarchist collectives using the legal arsenal of anti-terrorism, became an intrinsic part of deportation policies.

next...

The lexicon and register of action

3 Using direct action to raise awareness, obstruct and demonstrate at airports and detention centres, autonomists, libertarians and anarchists were committed to the fight against deportation in the 1990s and helped to shine a spotlight on detention, airports and air transport as contributing to the deployment of expulsion measures. The reinforcement of these measures had become a political issue in two senses from the 1980s onwards: as a tool of government control and for the repression of so-called “illegal” migration, and as a new issue for struggle and action.

The “collaborations” and complicities which allowed this system to operate and prosper

The chronology of this action, the emergence and disappearance of ephemeral or longer-lasting groups, collectives and networks which carried it out, the transformation of their watchwords and of the nature of their action reveal a field of action, of discursive construction and political theorizing against expulsion which illustrates the extent to which autonomous, libertarian and anti-authoritarian anarchists, acting together on a national and international scale, were involved in the fight around immigration control. The nature of the fight against deportation by air can be understood from the “Papers for all! Collective” [Collectif Papiers pour tous !] (1996-97), “Boycott and Harass Air France” [Boycottez Harcelez Air France] (BHAF, 1997), and the “Antideportation Collective” [Collectif Anti-Expulsions] (1998-2005, then 2006-2011). The anarchists were linked to, and on the one hand worked with the “sans-papiers” movement which developed in the 1990s (Blin, 2005; Diop, 1997; Cissé, 1999; Siméant, 1998) but they also helped to question the issues in these struggles and called for them to be broadened. In a constant dialogue between critical thought and direct action, they soon realised the limitations of merely demonstrating at airports and of the question of transport as possible levers for preventing deportation. The choice of airports as a target for action was accompanied by a deconstruction of deportation methods through a precise inventory of the public and private actors – political, economic, humanitarian – contributing to their workings. The aim was to look into all the “collaborations” and complicity which allowed this system to operate and prosper, highlighting in particular the indissociable interests of the state and of the capitalist system in the management of a foreign workforce, caught between control and exploitation. In this analysis of the social, economic, political and legal system underlying deportation, airports are, in some ways a symbol of the whole, the place which crystallizes, condenses and is the visible part of a complex whole whose ramifications are deeply rooted in all aspects of society. Airports thus become a sort of political synecdoche.

next...

4 At the same time the vocabulary of the texts and brochures published by anarchists in relation to the struggle against the deportation machine, refers explicitly to the crimes of the Second World War. Its aim is to denounce those who take part in and profit from this surveillance regime and the deportation of foreigners, and to turn the issue of deportation into an area of conflict; the words “deportation”, “collaboration”, “camps”, “round up”, “totalitarianism” and “concentration”, fallen into disuse in French because of their historical and symbolic connotations, were reintroduced as the keys to understanding what the anarchists considered to be a continuity between past and present. The risk of conflation and false analogies was not only accepted but became a political tool in its own right for alerting people to the routine normalisation of violent and oppressive situations which had become the standard framework of politics and largely went unnoticed, as is illustrated by the column’s title “Everyday chronicle of the war on immigrants” [Chronique ordinaire de la guerre aux immigrés] of the anarchist bulletin Cette semaine.

The expression “deportation machine” concentrates and synthesizes the anarchists’ description of all the workings of an expulsion measure, the industrial nature of which is, again, a more or less explicit reference to Nazi mass extermination. It spread in militant circles as a watchword for the dehumanisation and violence inherent in the system of forcible removal. The collectives that were formed in the 1990s and subsequently, all mention the “deportation machine”, which referred to the existence of the logistics and infrastructure needed for the routine deportation of foreigners. This materialist approach fixed the denunciation of the system of forcible removal firmly in a practical analysis of the organisations, methods, means and people that helped to carry out these policies.

While the state and capitalism were considered the enemies to beat in order to put an end to this system, in a direct continuation of the ideological matrix of anarchism as it had developed in the 19th century, the analysis of the “deportation machine” also revealed new issues such as the implication of organisations like the Red Cross which, under the guise of humanitarian aid, took part, according to the anarchists, in the deployment and legitimisation of these policies; or the role of business in the construction and maintenance of detentions centres; the involvement of transport companies in forcible removal. A reorganisation of watchwords, speeches and strategies for action on targeted issues was superimposed on the classic anarchist analysis based on a general critique of the state and capitalism.

The expression “deportation machine” soon spread beyond anarchist collectives

Moreover, the expression “deportation machine” soon spread beyond anarchist collectives in their struggle against expulsion. It was an issue for militants and investigators in the media and in academia. At the head of the Institute for Race Relations in England, Liz Fekete (2005) made this expression an issue when denouncing a hardening of migration policies and the statistics on the deaths and violence they caused. Her book, entitled The deportation machine: Europe, asylum and human rights, used newspaper reports and investigations by networks and organisations defending human rights to show the dehumanising and violent procedure inherent in these policies. “Deportation machine”, a gateway expression, had been widely used and in the 2000s became a tool for critique and struggle in militant and academic circles (Goodman, 2020).

next...

Collectif Anti-Expulsions, October 2003, Source : pajol.eu.org

5 This regeneration of the “deportation machine”, the identification of its various associated elements and the spread of a vocabulary for fighting against deportation, was accompanied by targeted actions and acts of sabotage at the offices of Air France, banks and detention centres etc. As the struggle launched by anarchists broadened and opened up, the issue of the detention of immigrants had to be detached from the idea that it was a specific kind of imprisonment, and be made a part of the general powers of incarceration. From the end of the 1990s onwards, the action of anarchists in airports, the appeal made to passengers inciting them to rise up and prevent deportations happening – planes becoming a microcosm in which new strategies of micro-insurrection were tried out – went hand in hand with a radical critique of detention which could be seen, for example, in the occupation of building sites where new centres were being built and in the demand for the closure of those already in existence.

In fact, the very issue of the struggle against deportation was to be reformulated through an appeal for an opening up of the struggle, such that immigrants would no longer be its specific, central figures, but instead the idea to be promoted was that of the common situation of foreigners and citizens in the face of job instability, societal control and powers of incarceration. From the anarchist perspective, the deportation machine became the way of attacking the state and capitalism as a whole. Thus the struggle against the deportation machine in relation to the traditional aims of the anarchist movement, can be interpreted from that point on as a lever for overthrowing the state and capitalism. That is why the state’s response to the action taken against deportation by these anarchist collectives seems particularly important in any understanding of the political issues of a struggle against deportation supported by watchwords and radical methods, if like Sayad we consider that “in thinking about immigration, the state thinks about itself” (Sayad, 2006 [1991]: 146). While in France and many European countries since the end of the 1990s all offenders against deportation procedures – first amongst whom were immigrants trying to resist their own deportation, as well as passengers on commercial flights opposing these measures – had been subject to intensified legal prosecution, it is equally important to reflect on the shift which took place when anarchist and anti-authoritarian action in autonomous struggles fell progressively under the cosh of the judicial system and anti-terrorism laws.

Intensified legal prosecution

The exacerbation of the legal prosecution of radical struggle seems to illustrate the fact that the struggle against deportation struck at the heart of the state’s interests. It was also part of a continuous history of intense repression and surveillance, as well as the judicialization by state authorities of real or imagined crimes attributed to the anarchist movement since its appearance in the 19th century (Woodcock 2019). If the groups which threatened the authority of the state and demanded its overthrow had been repressed, pushed into secrecy, dispersed and/or destroyed, state control and repression had also played its part in reinforcing these movements by legitimising their struggle and their watchwords. The fact that the anti-deportation struggle became a political and legal issue at the end of the 20th century also shows that the repression of these movements was a key element in maintaining and pursuing deportation policies. To put it simply, the repression and criminalisation of these movements were not an appendix to the use of deportation measures; not only were they an intrinsic part of it, but they guaranteed the persistence and the possibility of policies being contested by associations, collectives and/or simply by citizens. We must therefore include the issue of struggles and their repression in traditional analyses of the use of deportation measures by legal, police, political and humanitarian means.

next...

A brief chronology of anarchist struggles against the “deportation machine”

6 In his well-known history of anarchism, the writer, historian and poet George Woodcock explains that the failure of the anarchist attempt over the course of almost a century to found a lasting international organisation can certainly be explained by the spirit of anarchism itself, unwilling to accept any centralising structure or the very idea of representation or the formulation of a political programme. Its favoured matrix was the local group, which didn’t prevent exchanges between groups, the circulation of ideas or the spread of practice and of ways of taking direct action. According to Woodcock, the revival of the anarchist movement in Europe from the 1960s onwards broke with the original pattern of anarchism that had developed during the 19th century out of the issue of labour and social reorganisation freed from the state, and became attached to particular issues:

“Most anarchist groups have in fact been dedicated to individually motivated propaganda – either of the word or the deed – and in activity of this kind the lightest of contacts between towns and regions and countries is usually sufficient.” (Woodcock, 2019: 239)

This renewal of the anarchist movement is, according to Woodcock, based on issues such as the environment, feminism and nuclear disarmament. The emergence in the 1990s of small, autonomous groups which developed a matrix of critical analysis and direct action in relation to deportation measures, seems to fit into this analysis of the recent reorganisation of the anarchist movement around new fronts and targeted issues. But the apparently targeted nature of the antideportation struggle is in fact deceptive, as it is set against a background of more general watchwords: the overthrow of the state and capitalism, freedom of movement, the proclamation of the commonality of citizens and foreigners and a denunciation of incarceration powers, which follow in the wake of the ideas which were the breeding ground of 19th century anarchism. Collectives fighting deportation certainly renewed certain themes and objectives of the anarchist struggle, all the time maintaining the historical line of defiance and the attempt to overthrow the state and capitalism. This is also the reason why these minority, marginal groups are part of a process of critical deconstruction of, and attack against, the state, which makes them particularly vulnerable to surveillance and repression.

next...

7 The movement against deportation in France from the 1990s onwards sprang from small, ephemeral groups which have left no trace other than in anarchist archives, built up in publications on paper or on line, which chart the timeline of events (demonstrations, direct action at airports, targeted activism against the workings of the “deportation machine”) and pass on activist texts describing, for example, the establishment of camps for foreigners in Europe, the history of their imprisonment and of the deployment of deportation measures. Through the issue of the treatment of foreigners, the target was always the oppressive nature of the state and the institutionalisation, intrinsic to the creation of modern nation states, of the distinction between citizens and foreigners.

Groups have left no trace other than in anarchist archives

In 1996 the “Papers for all! Collective” took as its aim the fight against the French state’s xenophobic and discriminatory policy on foreigners:

“How are we to organise the daily struggle against discriminatory practices? The Collective has currently chosen two forms of action: slowing down the deportation machine and spreading information. It is up to everyone to try to disrupt the workings of control measures. Our aim: to prevent the application of xenophobic laws. It is entirely up to us, therefore, to act collectively and systematically against the administration offices or businesses which are involved in setting up the French state’s xenophobic policy.”

This aim was carried out in a series of occupations, one of which was at the Air France agency on the Champs-Elysées on 13th April 1996, and in challenges to the civil servants, mainly police, involved in deportation at a civil service demonstration on 17th October 1996. A flyer distributed at the time read “Civil servants! Refuse to work for a barbarous system!” [Fonctionnaires ! Refusez de fonctionner au service d’une logique barbare !] Defending the principle of freedom of movement and demanding a vote on a law regularising all undocumented immigrants, the “Papers for all! Collective” joined with the “3rd Collective of sans-papiers and residents of the Nouvelle France centre in Montreuil” in a spirit of openness, visibility and shared struggle. The close link with the sans-papiers movement and the joint occupation of the Odéon Theatre in Paris, made the opening of negotiations on the regularising of sans-papiers a priority for the collective. But this rallying to the war cry on the regularising of sans-papiers was severely censured by some militants, who criticised internally the movement’s loss of autonomy and its subordination to bureaucratic tasks centred on the question of regularisation alone. Dissention over policy also appeared with another movement “Young people against Racism in Europe” [Jeunes contre le Racisme en Europe ], which was born out of an international demonstration against racism and fascism in Brussels in 1992, and which, at that same period, went regularly to Roissy airport to protest against deportation. The “Papers for all! Collective” lasted less than a year, but the questions it posed and the reasons for its dissolution were issues for all subsequent collectives. Should they maintain complete autonomy or strategically rally to political parties and state bureaucracy in order to further targeted aims such as regularisation? Should they make the media a player in their strategy for communicating the aims of their struggle, or stick to complete confrontation, which implied standing back from public debate?

next...

8 “Boycott and Harass Air France” [Boycottez Harcelez Air France ] emerged in 1997 and stated in its appeal of 6th February that the slogan “Papers for all” and claiming the regularisation of sans-papiers were not enough, as they explicitly tried to set themselves apart from the “Papers for all! Collective”. While this slogan retained its importance, in so far as it refused to accept that the regularisation process should include classifying immigrants and favouring certain categories of sans-papiers, it had to go hand in hand with direct action against the “deportation machine” in which planes played a key part. The text “Eliminate the deportation machine”, which spelled out the origins of the “Boycott and Harass Air France” (BHAF) campaign that was presented as “a tool for consciousness raising and action against one of the elements of the repressive, anti-immigrant armoury”, underlined the role of airline companies, a central, routine part of deportation measures:

“Even though a not inconsiderable number of deportations are carried out by train or by boat, airline companies are the centrepiece of deportation measures, with boarding being the most direct moment of the forced deportation process and at the same time the moment which is becoming more and more routine (little by little every passenger will have to get used to travelling next to one or two deportees) and it is the most civil, the most social moment of the immigrants’ journey through police/justice/detention camps/deportation”.

The boycott and its negative publicity were not to be limited to an individual act of refusal, but had above all a political aim: the rejection of deportation and freedom of movement for all. The fact that the company was so well known meant that this campaign calling for a boycott attracted particular attention, like the petition signed by “more than 50 intellectuals, film makers, lawyers and citizens calling for a boycott of Air France”. BHAF asked Air France to stop taking part in deportation, emphasising the problem this posed to their clients and employees. But this fight was also carried out in the name of equal rights; the hardening of the state’s attitude to the rights of foreigners was merely a prelude to the attacks that would soon be made against citizens who could expect to face increasing social insecurity. Looming here was the idea that the fight for sans-papiers could not be separated from the social struggle for global justice.

The hardening of the state’s attitude to the rights of foreigners

The collective occupied Air France agencies in Paris, Lyon and Lille on 4th February 1997 and in the context of wider protests against the Debré law, called for the boycotting and harassment of Air France. In March and April 1997 Air France agencies in Paris, Lyon and Lille were occupied and damaged, and an Air France desk at Roissy airport was blocked to stop a deportation. Then, over a period of more than ten years, the airline became the favourite target for action, either by this collective or by others which came after it, in the attempt to denounce the system of deportation on commercial flights, and more broadly the control and repression of undocumented immigrants. While the airline never responded to these appeals from libertarian collectives other than by taking legal action against them for the damage to their agencies or for the disturbances on board planes brought about by attempts to prevent deportation, there was within the company a gradual opposition to and rejection of the use of civil aviation as the means of carrying out government decisions on migration control. In this sense, while the actions of anarchist collectives brought no official response from the company, they certainly contributed to fostering an awareness amongst professionals of the violence of these policies and encouraging their opposition to the use of commercial flights for these measures.

next...

9 The first French collectives to take action at airports consequently operated alongside new movements against deportation, chiefly because sans-papiers organised themselves into movements which sought to free themselves from the hierarchies and paternalism of the citizens’ collectives in defence of immigrants (Stierl et al., 2021). But their existence was short-lived, and they were often weakened by disagreements over strategy, essentially over whether to be part of the bureaucratic regularisation of sans-papiers or to reject the principle and call for a boycott intended to denounce the complicity of the company whilst legitimising its underlying commercial and profit-making motives.

The “Antideportation Collective” [Collectif Anti-Expulsions] (CAE), founded on 7th April 1998, developed and intensified their direct action at airports. The collective signed a six-page manifesto entitled Freedom of movement for all [Libre circulation pour tous !] in September 1998. Thereafter there was a direct action operation over time which drew on both existing protests by passengers travelling on flights on which deportees were regularly carried and whose nationality they shared, and a desire to formalise them so as to incite as many people as possible to block these measures. They encouraged passengers to remain standing, which prevented the plane from taking off. To this end, the CAE organised regular airport action which linked different kinds of struggles and participants. The members of the collective were continuing the fight of sans-papiers, and the anarchists often highlighted in their publications that their struggles were based on the resistance strategies which the immigrants had first put in place to try to avoid deportation. The airport has, moreover, been periodically targeted by sans-papiers collectives, such as the “Coordination of sans-papiers 75” [Coordination 75 des sans-papiers] (CSP 75), who went to the airport to protest against the deportation of a fellow countryman, or the Black Vest movement which organised a sit-in by several hundred people on 19th May 2019 in terminal 2 of Roissy-Charles de Gaulle (Gilets noirs, 2019). But for illegalized immigrants, the airport was by definition a place where they were extremely exposed and extremely at risk, including in collective demonstrations, because they could at any moment be arrested and placed in detention, then deported. The advantage for militants belonging to anarchist, libertarian and anti-authoritarian collectives lay in the protection given to them by their nationality, in contrast to the risks run by illegalized immigrants in the airport itself.

The “Antideportation Collective” organised regular actions at the airport, the aim of which was firstly to alert passengers on these flights and incite them to take a stand against these measures. The action thus involved information passing between the activists and the passengers, a kind of mediation between them. The collective’s aim was that their guidance on how to act on board to prevent deportations should be appropriate and shared, by means of the distribution of an action guide for passengers and for militant networks in France and abroad. This formalised a real modus operandi so that passengers could become agents for preventing deportation. This was accompanied by support for passengers who were questioned, in the context of the growing judicialization of all forms of protest, organised or spontaneous, aimed at stopping deportations. The campaign organised by the “Antideportation Collective” to defend passengers charged after protesting on board against the deportation of a foreigner, principally consisted of the publication of a standard letter sent in October 2003 to the CEO of Air France by many signatories, and the occupation of Air France agencies in November of the same year.

next...

10 But the position defended by the “Antideportation Collective” was that their action could not either be limited to or summed up by their action at the airport, and had to be seen as a fight against all the component parts of a punitive, surveillance society whose treatment of foreigners was powerfully instructive:

“Going to airports to protest against deportation is the same thing as being against detention centres, waiting zones and prisons, it’s being against all forms of imprisonment, against everyone’s records being held by the SIS [Schengen Information System] or elsewhere, against all forms of control and repression, against all forms of exploitation; but it is also to be against the courts, it is to refuse their rules, their laws, which maintain social control and institutionalise exploitation. It is to fight for freedom of movement and the freedom to reside”.

To fight for freedom of movement

Between 1998 and 2000 the “Antideportation Collective” took action in various places of detention, such as the offices of the Border Police and their waiting zone at the Gare du Nord, the detention centre at Vincennes, the Ibis Hotel at Roissy, used for detention, the new waiting zone “ZAPI 3” at Roissy (see Maréchal, this volume), but also Air France agencies and the desks of airline companies.

Another collective, also called “Antideportation Collective”, was re-created between 2006 and 2011, after the dissolution of the first CAE in 2005. It is important to clarify that the majority of the archives at our disposal were put together by this second collective which, while carrying out considerable work on the historical records of anarchist struggles against deportation since the end of the 1990s and establishing a detailed chronology of the demonstrations, actions and sabotage carried out against the deportation machine, also offered a retrospective reading and critique of the meaning of these movements, their aims and their limits. The second “Antideportation Collective” pushed for a radicalisation of the methods used by previous collectives, calling for attacks of sabotage, destruction and disruption on all aspects of the deportation machine and refusing any form of political mediation. Thus, the airport was no longer central to activism, even if its strategic importance in trying to stop individual deportations was not ignored. In the 2000s, whereas the French state continued to increase its powers in relation to administrative detention, which included a lengthening of the detention period and routine deportations on commercial flights, anarchists, libertarians and anti-authoritarians defended the idea of a struggle which attacked the complexity and the tangle of political and economic interests which constituted the deportation machine.

next...

Opening up the “deportation machine”: chains, links and collaborations

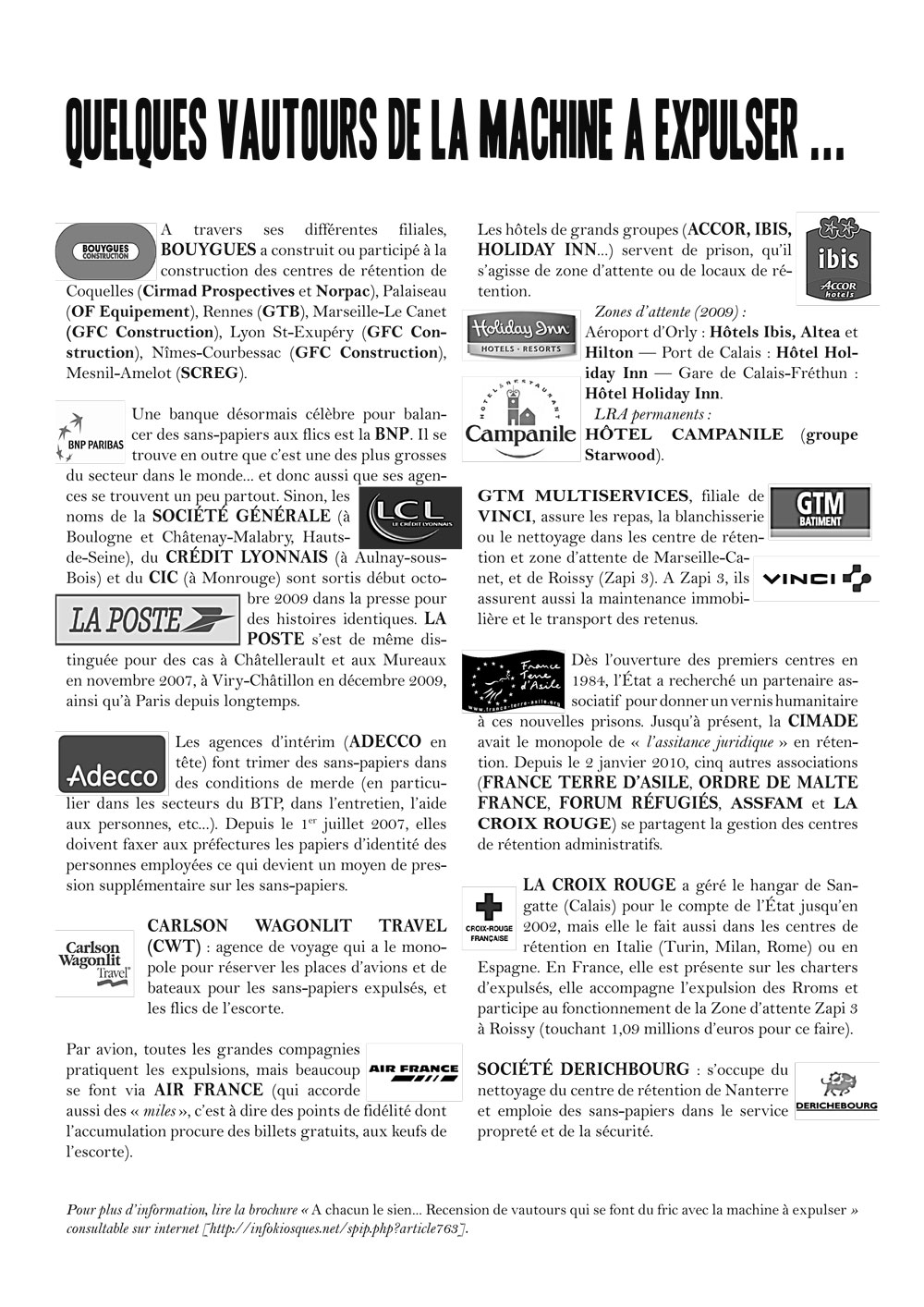

A flyer reproduced in the « A chacun le sien... Recension de vautours qui se font du fric avec la machine à expulser » Source : http://infokiosques.net/spip.php?article763

11 We believe it is important to set the demonstrations, acts of sabotage and distribution of tracts carried out against the deportation machine by anarchist movements in an initial analytical framework, which consists of literally opening up the deportation system by identifying, listing and making public the companies, organisations and people that are stakeholders in an assemblage which cannot be reduced to the act of deportation alone, but includes administrative detention, economic actants and associations. The tide of anarchism, whether in France or in other European countries such as Belgium, Italy or Greece, thus sheds light on the logistics and infrastructure of the deportation machine in the 2000s; this includes companies in the public building and works sector and their subcontractors who built detention centres, the companies that provided day to day maintenance and catering, the transport services (planes, buses, trains, boats) used for moving foreigners within the country and for deporting them, the lawyers, and the associations offering help to foreigners which, like Cimade, operated in detention centres and contributed to their legitimacy as institutions.

A whole financial-industrial-humanitarian structure

This inventory of the public and private actors in the deportation machine, and the profit motive underlying their participation in the system, take deportation from being an abstract right inherent to state sovereignty, to becoming an issue and interest for a whole financial-industrial-humanitarian structure. Seen from this perspective, the aims and political symbolism of deportation are indissociable from a consideration of this structure in terms of its profitability and the return for private enterprise. Militant anarchist practice thus deconstructed the abstract political concept of expulsion and gave a pragmatic and materialist reading of practice, logistics and infrastructure, which raised the question of the joint interests and profits of the state and capitalism. In this respect, through this exercise in the historical contextualisation and political theorisation that accompanied their activism, anarchists established a sort of critical mapping of the organisation and collaboration that was necessary to the deployment of a deportation policy, at a time when the research field was still thinking of deportation policies in terms of rights, politics and the administration. The expression “deportation machine” is thus emblematic of the desire to understand the mechanisms of a policy, its workings, its actors, etc. In some respects, deportation appears to be a matrix in which the question of the treatment of undocumented foreigners allows us to understand all aspects of social and political life, and notably the indissociability of private and public interests, and the complementarity of police action and humanitarian aid measures (Fischer, 2013; Andersson, 2014).

next...

12 These connected interests and profits reveal a system for deportation co-produced by various actors, sometimes seen as heterogenous but in fact complementary and co-dependent. Deportation measures are based on and reveal the co-construction of the state and the market society. The deportation machine is made up of transport companies, those who build detention centres, agencies which make flight reservations on behalf of the state, banks which confiscate the money of immigrants once they have been deported, unions which have helped to make work essential to allowing immigrants to stay in the country legally and an essential criterion for their documentation by the authorities, at the expense of all other criteria, NGOs and the humanitarian sector as stakeholders in deportation measures and their legitimisation.

Anarchist collectives thus carry out repeated campaigns denouncing the active part played by the Red Cross in detention, repression and deportation measures:

“The hand must attack what the heart cannot accept. Round-ups and deportation can only work with the help of companies like Bouygues which build prisons and detention centres, of banks like the BNP which turn away illegal immigrants who try to open an account, of organisations like the Red Cross which assist in the running of detention camps, of hotels like Ibis or Mercure which grow fat by becoming “waiting zones”, of transport companies like Air France which carry out deportations or the RATP which carries out screening on behalf of the prefecture.”

The identification of a variety of targets in the fight against deportation became a shared resource for spreading and multiplying movements in several European countries. Publications on anarchist websites dated and identified action carried out in Belgium, Germany and Italy under the heading “Notes on disruption”. In Italy, where the movement seems to have been particularly active, a series of actions took place in 2005 against transport companies, banks, the police and the Red Cross in the name of the struggle against detention. In Parma, action was claimed to have been taken by the Cooperativa artigiana fuoco e affini (occasionalmente spettacolare) against detention centres and deportations: “The Bnl [Banca Nazionale del Lavoro] finances the war and immigrant camps. Troops out of Iraq, destroy detention centres”, “The Red Cross runs the Piandel lago CPT [centro di permanenza temporanea]: solidarity with immigrants”.

next...

Stickers from the campaign against the Red Cross, by the Collectif Anti-Expulsions, October 2003, Source: pajol.eu.org

Reformulating the issues and aims of the struggles: incarceration powers and the proclamation of a common condition

13 Part of the criticism directed at the “Papers for All! Collective” had consisted of denouncing the impasse of fighting for regularisation, which made the state the only legitimate partner in discussion and the only arbiter of legality, and which played on the ambivalence between its repressive action on imprisonment and its prerogatives in relation to regularisation. The French state had certainly, from the start of the movement by illegalized immigrants, used the power of regularisation with the aim of both appeasing and dividing the struggles, because entering into negotiations meant choosing discussion partners and legitimising some while disqualifying others. Regularisation had furthermore a double function: that of responding both to the indignation aroused by the immigrants’ situation, and to a utilitarian logic in terms of the economy. It could thus be simultaneously used by the authorities as a tool for “pacifying” social movements and as an economic tool to help employers. It is understandable that regularisation should have been considered not only insufficient, but also deleterious and counterproductive by anarchists, since it is based on the principle of entering into negotiation with state services and consolidates their legitimacy. The development of French anarchist collectives in the 2000s seems to have consisted in turning their back on the aim of regularisation (which on the other hand remained central to undocumented immigrants’ collectives) in order to try and create direct, full-on confrontation with the state.

Moving beyond a struggle centred on the question of regularisation alone seems to have been looked for in the convergence of the fight around prisons and the fight against detention and deportation through a process of identifying incarceration powers which, replacing just the specific forms of imprisonment for foreigners, would now become the object of struggles. This connection between prison and detention became tangible in 2006-2007 with action both aimed at and coming from prisons and places where illegalized immigrants were detained, and in the continued struggles of European anarchists who extended and generalised reflection on incarceration, starting from the issue of the detention of foreigners.

next...

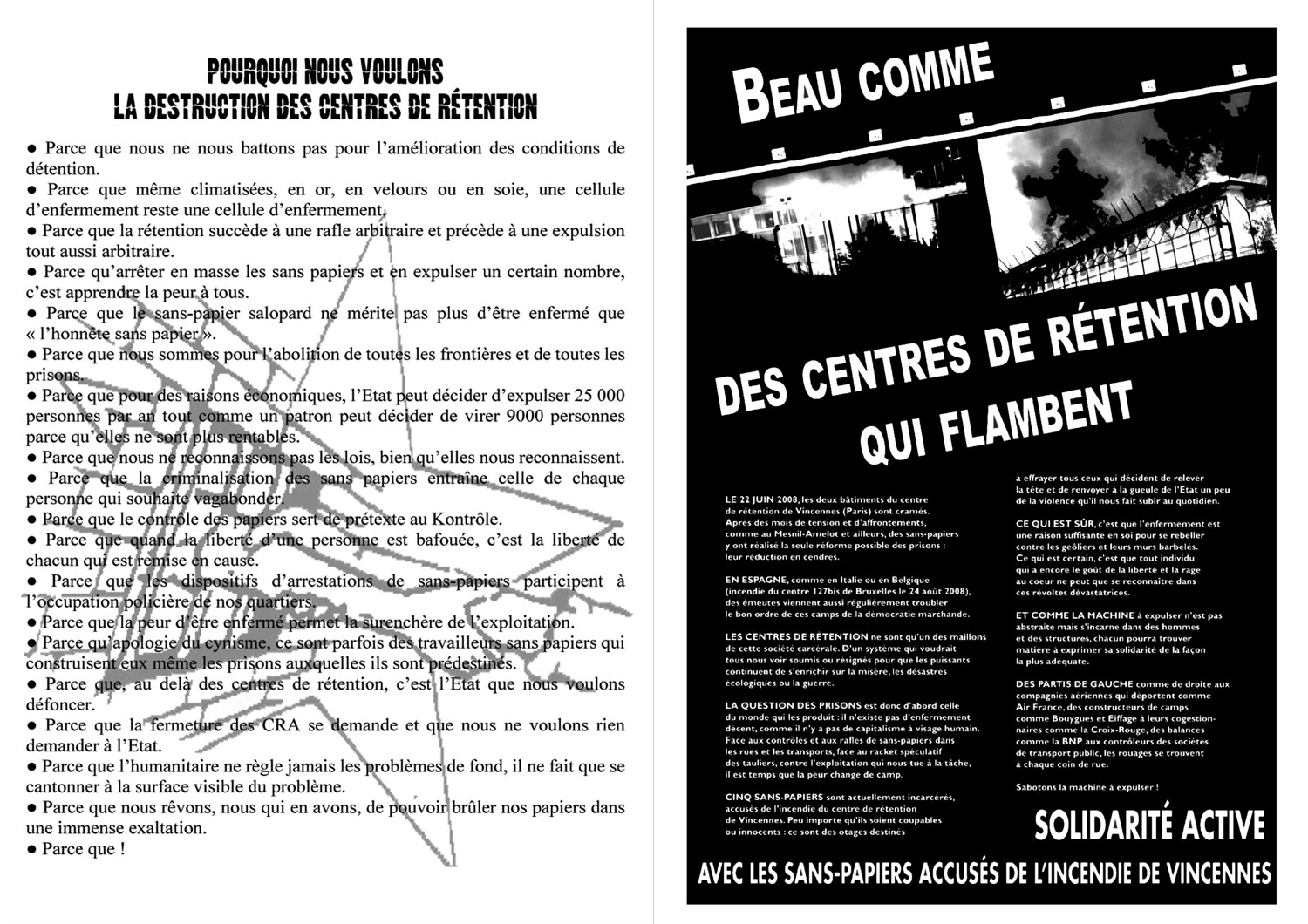

14 A political perspective – anti-reformist and abolitionist – hardened around detention. Two flyers entitled “Why we want detention centres destroyed” and “Beautiful as burning detention centres” listed the arguments against pursuing any kind of improvement or humanisation of these centres. On the contrary, condemning them on principle and calling for their destruction was to be constantly upheld and stated. In 2008 this abolitionist approach was accompanied by fires, escapes and revolts in detention centres in France, Spain, Italy and Belgium. On a poster in Brussels in 2008 was written “Spread the revolt… Destroy closed centres and prisons”. In this way European anarchists linked the fight against detention centres and against the deportation machine to the prison question. They also used the slogan “They call it a detention centre, but it’s a prison”, in an echo of the movements which took place around prisons in the 1970s and of the way Foucault had made the prison question a theme by extending it to all the institutions which had historically contributed to setting up disciplinary technology at the heart of nation states (Foucault, 1975).

“Spread the revolt… Destroy closed centres and prisons”

The 2000s witnessed the development of a protest movement against detention centres, to which the anarchists added action and publications, but which first and foremost had its origins in the exhaustion and anger of imprisoned foreigners. Between December 2007 and March 2008 there were fires at detention centres in the Paris region, in the provinces and in several European countries. The simultaneous nature of these fires seems to correspond to the analyses carried out by Hardt and Negri (2000) on the “cycle of struggle”, in which a movement spreads simultaneously around issues and common protest action beyond frontiers. The fires in these centres were in fact part of a European movement for the abolition of centres and against detention. A feature of the actions which took place was that they enabled contact between the inside and the outside of these centres, with acts of sabotage and demonstrations on the outside prolonging the acts of destruction carried out on the inside by imprisoned foreigners. In 2007-2008 the anarchists established links with mutinous detainees. Following these events, there were campaigns in support of anarchists against whom legal action was being taken, and the foreigners who had started the fires.

next...

Caption of the first image (left) : Parisian anarchist collective Non Fides’ flyer, 2008 Source : non-fides.fr. Caption of the second image (right) : Poster, 2008 Source : non-fides.fr

15 The action of the anarchists had an underlying political purpose which was at one and the same time the critical deconstruction of the state and capitalism, and a critique on the structure, hierarchies and power relationships inherent in the struggle. For the purposes of deconstructing the places occupied in this struggle and their objectives, a central point in anarchist thought was a critique of the isolation and objectivization of the immigrant. The principle of any specific struggle, that it should be led by those who were able to be the defenders of an immigrant “cause” or by the immigrants themselves in various kinds of self-organisation, was not only denounced and called into question, but considered responsible for the perpetual renewal of the state categories that had to be erased. The anarchists mentioned the class and power issues which ran through the struggle, including through the organisation of the movement and of the illegalized immigrants’ collectives. The very issue of the anarchist struggle was thus subject to a shift, a relocation of the immigrant as the subject of oppression in the direction of an aspiration to a common struggle, in which citizens and foreigners would stand side by side to denounce the conditions of shared oppression, made up of control, generalised surveillance and global instability.

Our demand for reciprocity

The idea of reciprocity between all those involved in these struggles, whether they were nationals or foreigners, was a condition for rethinking a struggle which was not to be centred around the issues relating to the situation of illegalized foreigners alone, but around anarchist watchwords:

“This is the meaning of our demand for reciprocity. Rather than continuing a link which has no purpose other than to maintain the fiction of a political subject who would have, by virtue of his status as the principal victim, a monopoly on reason and thus on the struggle, we have many other paths to explore. To put it more clearly, we could say that solidarity needs a reciprocal recognition in acts and/or in ideas. It is in fact difficult to feel solidarity with a sans-papier claiming regularisation for himself and his family while being not in the slightest bit interested in the destruction of detention centres”.

The desire to fight against a system rather than against specific, targeted issues, even if they were emblematic of the injustice and violence in the situation of immigrants, is a typically anarchist position. An equally essential point in anarchist thought on the politics of struggle can be found in the idea of un-mediated struggle, that is, not only without a representative or spokesperson, but also freed from the supervision of unions, associations and NGOs which direct movements according to particular interests. We can thus see that the apparently targeted aim of the fight against deportation is in reality based on the more general motive of overthrowing the system, which has been a part of anarchist movements since their beginnings:

“The democratic mechanism of citizenship and rights, even though widespread, will always presuppose the existence of people excluded from it. Criticising and trying to prevent the deportation of immigrants means criticising in actuality both racism and nationalism; it means looking for a common area of revolt against capitalist alienation which touches us all; obstructing a repressive mechanism that is as significant as it is hateful; it means breaking through the silence and indifference of civilized people who stand back and watch; it means, finally, debating the very concept of law, in the name of the principle that ‘we are all illegal’. In short, this is an attack on one of the pillars of government and the class system: competition between the poor, the replacement, nowadays increasingly threatening, of social warfare by ethnic or religious warfare. […]”

next...

Struggles against the “deportation machine” and the heart of the state: reflections on the criminalisation of movements.

16 The disturbances on commercial flights resulting from deportees themselves struggling against being put on board (Kinté, 2020) or from passengers protesting against the presence of a deportee on the flight, were initially the object of condemnation from a moral point of view, but they were swiftly followed by legal prosecutions. In 1998, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, the French Minister of the Interior, stigmatised the action of both “Young people against racism in Europe” [Jeunes contre le racisme en Europe] and passengers who, at Roissy and on board planes, tried to hinder deportations; he explicitly called for sanctions to be taken against the “troublemakers”, accused of “anti-social conduct”. Protests on board flights were thus the object of increased legal action, which contributed to the atmosphere of intimidation and fear around possible action opposing deportation measures. At the start of the 2000s, the border police (PAF) began to hand out to passengers a form indicating that they would be liable to prosecution if they were to obstruct the deportation process, and at the same time the militants of the “Antideportation Collective” produced their guide which explained to passengers what to do to make it easier for the captain to have the foreigner to be deported taken off the plane. The simultaneous distribution of the police form and the anarchist guide to action in airports demonstrates the confrontation between a police technique aimed at intimidating passengers and creating an environment likely to stymy any act of rebellion (even though these were entirely peaceful and non-violent), and a mobilisation strategy in which passengers could play a decisive role, with the captain of the plane being the final arbiter in this standoff and the person responsible for deciding to keep the detainee on board or to have them taken off the flight (Hamant, Lecadet, 2019).

A police technique aimed at intimidating passengers

next...

17 In the early 2000s, the strategy of the “Antideportation Collective” was to concentrate its action on airports in order to prevent deportations, and also to turn a part of its efforts to campaigns in support of passengers prosecuted by Air France and liable to charges. The field of action widened to include the courts, an essential element in understanding how deportations finally became routine and gained a foothold as an almost ordinary part of civil aviation. The campaigns by anarchist collectives as well as the media coverage which the passenger prosecutions attracted, seem to have played in favour of a reduction in penalties and in the demands of Air France which settled on a symbolic claim of one euro in damages from passengers, but the campaigns did not prevent these court cases from playing a decisive dissuasive role. These movements no doubt had an impact both in reducing the penalties for rebellious passengers and influencing government decisions on finding some sort of balance between “open” public deportation practice on commercial flights and organising charter flights which generally took off from airports or airport zones closed to the public, giving at first sight little opportunity for attempts by militants to obstruct the process. It was in fact because of these charter flights that new resistance strategies, consisting of blocking planes and preventing them from taking off, were developed in the 2010s, particularly in the United Kingdom. The most striking case was that of the “Stansted 15 collective” (Brewer, this volume) who on 28th March 2017 managed to prevent the departure from Stansted of a charter flight to Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone by chaining themselves to the aeroplane undercarriage. The collective was prosecuted and found guilty of acts of terrorism, a verdict that was revoked on appeal. This well-publicised trial showed how the obstruction of deportation was gradually handled with legal reserve, revealing the place occupied by such movements in state security and legal strategies.

Returning to the French context at the start of the 2000s, the difference between the legal actions initiated against passengers for “obstructing movement in an aircraft” and those brought against anarchists following the occupation of and damage to various Air France agencies, was that some of the latter were beginning to be brought in the name of anti-terrorism, with legal and penal implications that were out of all proportion to those applied to passengers. Members of the “Antideportation Collective” faced prosecution on several occasions. Resistance to deportation therefore no longer consisted simply of action against the deportation machine and its various elements, but also of campaigns and strategies to try to oppose the increasing tendency for activists to be taken to court: support for those charged, attendance in court etc. This shift can be explained by a more general contextual element: the tendency for legal action against the anarchist movement to be taken in terms of antiterrorism. But this change can also be interpreted in the light of the place accorded to the issue of the control of foreigners in the “thought process of the state” [pensée de l’Etat] (Sayad, 2006 [1991]) and of the hierarchy and order of its security worries.

The action of anarchist collectives against deportation thus served to reveal the centrality of deportation measures in current governmentality and of the threat which organised opposition constituted in the eyes of the state. We also believe that an analysis of deportation policies cannot be based solely on contrasting the legal, political and police measures which enable deportation to be carried out with the opposition to them; it must also include and make sense of the way in which the legal prosecution of all forms of obstacles to these measures have gradually become an intrinsic part of them, upholding their continued deployment. The breadth and the gravity of legal prosecutions show that these movements are considered as hitting at the heart of the security of the state.

next...

18 Let us conclude this essay by situating this point about the inflationary nature of the state’s response to antideportation activism in a wider understanding of the politics of deportation itself. It is clear that deportation itself is in no way reducible to controlling immigration, border policing, and upholding the integrity of the asylum process – functions that officials often cite as its main aims and justifications. The fact that an enforcement or implementation “gap” exists (Paoletti, 2010), that so many of those exposed and vulnerable to deportation are not in fact expelled, attests to this. Deportation is as much a form of political performativity, a harsh and violent mode of signaling about borders and memberships, as anything else. In this way the prosecution of antideportation activists, and the repression of anarchist movements, overlaps and resonates with this political and symbolic logic of deportation. It too becomes an occasion for the performance of the state’s sovereign power. But this is not a space that the state can monopolize or fully control. The struggles we have documented here attest to the undecidability and generative excess of antideportation.

Anarchism illuminates the politics of deportation

But anarchism illuminates the politics of deportation in other ways as well. In this contribution we have called for scholars of migration to take anarchist and anti-authoritarian movements seriously. Anarchism is certainly not a mass movement. It is not even a stable field, for, as we have seen, groups and networks come and go. Why, despite their fringe status, do these movements merit attention? It is precisely because anarchists refuse to take the very existence and form of the state and capitalism for granted that they open up a line of visibility on the migration field that is otherwise closed to many scholars. Familiar criticisms that anarchism is unworkable or utopian are wide of the mark in this respect. Anarchism denaturalizes that which is given to us as relatively fixed. As such, it offers a way to see deportation differently.

next...

Sources

19

« A chacun le sien... Recension de vautours qui se font du fric avec la machine à expulser », 23 December 2009 https://www.infokiosques.net/spip.php?article763

“Aux errants, Agli Erranti”, in Cette Semaine n°85, August/September 2002 https://infokiosques.net/lire.php?id_article=757

“Brèves du désordre italiennes” in Cette Semaine n°88, March 2006.

“Brèves du désordre grecques” in Cette Semaine n°88, March 2006.

“Brèves du désordre belges” in Cette Semaine n°90, September 2006.

“Brèves du désordre allemandes” in Cette Semaine n°91, December 2006.

Corps Perdu, n° 1, December 2008 http://www.acorpsperdu.net

Courant alternatif, monthly published by the libertarian communiste organisation, June 1997. https://archivesautonomies.org/IMG/pdf/communismelib/courantalternatif/ns/courant-alternatif-serie2-n070.pdf

“Faisons en sorte que cet euro leur coûte très cher !”, 2003 http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article276

“Guide pratique d’intervention dans les aéroports”, Vacarme, 2000, vol. 3, n°13, p. 14-18.

“Interventions contre les expulsions : quelques pistes”, July 2004, http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article644

“Lettre au président d’Air France de protestation contre les expulsions”, 8 December 2003, http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article278

“S'opposer aux expulsions ?”, Plein droit, 62, 2004, p.35-38.

Une lutte contre la machine à expulser [Paris, 2006-2011], 2017, Paris, Mutines Séditions.

next...

Bibliography

20

Feu au centre de rétention. Des sans-papiers témoignent, 2008, Paris, Libertalia

« Gilets Noirs, pour rester en colère et puissants ! », Vacarme, vol. 88, n° 3, p. 68-79., 2019

Andersson, Ruben, 2014, Illegality, Inc. Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe, Oakland, University of California Press.

Atac, Ilker, Rygiel, Kim and Stierl, Maurice, 2021, “Building transversal solidarities in European cities: Open harbours, safe communities, home”, Critical Sociology, 47(6), p. 923-939.

Blin, Thierry, 2005, Les sans-papiers de Saint-Bernard. Mouvement social et action organisée, Paris, L’Harmattan.

Cissé, Madjiguène, 1999, Parole de sans-papiers, Paris, La Dispute.

Diop, Ababacar, 1997, Dans la peau d’un sans-papiers, Paris, Seuil.

De Genova, Nicholas (ed.), 2017, The borders of ‘Europe’: Autonomy of migration, tactics of bordering, Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

Fekete, Liz, 2005, The deportation machine: Europe, asylum and human rights, European Race Bulletin, n°51.

Fischer, Nicolas, 2013, “Negotiating Deportations: An Ethnography of the Legal Challenge of Deportation Orders in a French Immigration Detention Centre”, in Anderson, Bridget, Gibney, Matthew and Paoletti, Emanuela (eds.), The Social, Political and Historical Contours of Deportation, New York, Springer, p. 123-142.

Foucault, Michel, 1975/2007, Surveiller et punir : naissance de la prison, Paris, Gallimard.

Garelli, Glenda and Tazzioli Martina, 2013, “Challenging the discipline of migration : Militant research in migration studies, an introduction”, Postcolonial Studies, 16(3), p. 245-249.

Goodman, Adam, 2000, The Deportation Machine: America's Long History of Expelling Immigrants, Princeton University Press.

Hamant, François, Lecadet, Clara, 2019, "Des pilotes contre les expulsions. Entretien avec François Hamant", Vacarme, n°88, p. 80-87.

Hardt, Michaël and Negri, Antonio, 2000, Empire, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

King, Natasha, 2016, No borders: The politics of immigration control and resistance, London, Zed Books.

Kinté, Kounta, 2020, "Comment rater l’avion. Stratégies de résistance à l’expulsion", Jef Klak, n°5.

Lessana, Charlotte, 1998, "Loi Debré : la fabrique de l'immigré (Partie 1)", Cultures & Conflits, 31-32 https://journals.openedition.org/conflits/549

Mezzadra, Sandro, 2004, “The right to escape”, Ephemera, 4(3), p. 267-275.

Micinksi, Nicholas, 2019, “Everyday coordination in EU migration management: civil society responses in Greece”, International Studies Perspectives, 20, p. 129-148.

Mudu, Pierpaolo and Chattopadhyay, Sutapa, 2016, “Introduction: Migration, squatting and radical autonomy” in Mudu, Pierpaolo and Chattopadhyay, Sutapa (eds), Migration, squatting and radical autonomy, New York, Routledge, p. 1-32.

Nyers, Peter, 2010, “No one is illegal between city and nation”, Studies in Social Justice, 4(2), p. 127-143.

Paoletti, Emanuela, 2010, “Deportation, non-deportability and ideas of membership.” Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series n°65, University of Oxford, July, URL: https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/files-1/wp65-deportation-non-deportability-ideas-membership-2010.pdf

Sayad, Abdelmalek, 2006 [1991], L’immigration et les paradoxes de l’altérité 1. L’illusion du provisoire, Paris, Raisons d’agir éditions.

Siméant, Johanna, 1998, La cause des sans-papiers, Paris, Presses de Science-Po.

Stierl, Maurice et al., 2021, “Struggle” (multi-authored) in “Minor Keywords of Political Theory: Migration as a Critical Standpoint”, A collective writing project involving 22 co-authors; coordinated, co-edited, and introduced by De Genova, Nicholas and Tazzioli, Martina, Environment & Planning C: Politics and Space.

Walia, Harsha, 2013, Undoing border imperialism, Oakland, CA, AK Press.

Walters, William, and Lüthi, Barbara, 2016, “The Politics of cramped space: Dilemmas of action, containment, and mobility”, International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 29(4), p. 359-366.

Woodcock, George, 2019, L’anarchisme. Une histoire des idées et mouvements libertaires, Québec, Lux Editeur.

next...

Notes

21

1 There are at least two ways in which anarchism appears within migration scholarship. First, scholars of social movements have explored the contribution of anarchist practices, spaces and ethics to solidarity movements, including the creation of squats and other social centres dedicated to hosting people on the move (e.g., Micinski, 2019; Mudu and Chattopadhyay, 2016; Ataç et al, 2021). Second, certain strands of anarchism and autonomism, often in conversation with Marxist and post colonialist traditions, inform radical theories and critiques of borders, migration control and the statist governance of citizenship (e.g., Mezzadra 2004; King 2011; Nyers, 2010; Walia 2013; De Genova 2017).

2 In the documentation which forms the basis of this article these three terms are used to qualify the movements which claim to be part of the struggle against the deportation machine. They nonetheless cover specific historical turning points in the evolution of the anarchist movement. While the issue of autonomy as a process of emancipation from the state and capital is part of the 19th century anarchist movement, the autonomous movement as such is dated by historians from 1968, with the appearance in Italy, Spain, France and Germany of groups influenced by Leninist, situationist and councilist ideas which advocated insurrection. It appears, however, that the collectives which were formed to fight against the deportation machine have only a distant relationship with the historical development of the autonomous movement.

3 In 1996, the involvement of the “Papers for all! Collective” in the actions of the “3rd Collective of sans-papiers and residents of the Nouvelle France centre in Montreuil” [3ème Collectif de sans-papiers et des résidents du foyer Nouvelle France à Montreuil], and the involvement of its members in the administrative task of sending in applications for legalisation, which will be covered later, demonstrate the comradeship between the sans-papiers movement and the anarchists, but they were also the cause of lively tension and criticism over the form that the fight against deportation should take. As can be seen in the development of the strategies of anarchist collectives in France and in Europe in the 2000s, focusing only on the question of the regularisation of undocumented immigrants was not only seen as insufficient, but also doing a disservice to a radical struggle against the deportation machine.

4 In Une lutte contre la machine à expulser [Paris, 2006-2011], 2017, Paris, Mutines Séditions, p. 24 and 39.

5 “L’Etat se pense lui-même en pensant l’immigration”.

6 “Comment organiser au quotidien la lutte contre les pratiques discriminatoires ? Le Collectif a, pour le moment, choisi deux formes d’intervention : des actions visant à freiner la machine à expulser et un travail d’information. A chacun et chacune d’essayer de perturber le fonctionnement des divers rouages du dispositif de contrôle. Objectif : empêcher l’application des lois xénophobes. Il ne tient donc qu’à nous d’intervenir collectivement et systématiquement dans les administrations ou entreprises qui participent à la mise en place de la politique xénophobe de l’État français.” In Une lutte contre la machine à expulser [Paris, 2006-2011], Ibid., p. 301.

7 “Un outil de conscientisation et de mobilisation contre un des rouages de l'arsenal répressif anti-immigré” in Courant alternatif, monthly published by the libertarian communiste organisation, June 1997, p. 7. https://archivesautonomies.org/IMG/pdf/communismelib/courantalternatif/ns/courant-alternatif-serie2-n070.pdf

8 “Même si une fraction non négligeable des expulsions sont effectuées par train ou par bateaux, les compagnies aériennes sont des pièces maitresses du dispositif d’expulsion, l’embarquement constitue le moment le plus concret de la procédure de déportation forcée et en même temps le moment qui tend le plus à se banaliser (petit à petit chaque passager devra s’habituer à voyager aux côtés d’un ou deux expulsés) c’est le moment le plus civil, le plus « social » du parcours police/justice/camps de rétention/expulsion.” “Enrayons la machine à expulser”, Ibid., p. 7-8.

9 Ibid., p. 9.

10 Faced with campaigns that demand that particular airlines cease to engage in the deportation of illegalized persons, airline officials have sometimes insisted they have no choice. For instance, when challenged on its involvement in the removal of failed asylum seekers, a British Airways spokesperson stated that: “It is UK law and we comply with it – it’s like asking whether we are happy paying income tax”. (“Major airline refuses to help with forcible removal of immigrants”, The Independent, October 8, 2007.) Given how successful some of the world’s largest companies have been at avoiding paying corporate tax, the analogy is rather telling!

11 The law of 24th April 1997, which included several provisions relating to immigration, was part of a series of laws known as “Pasqua-Debré laws” which between 1986 and 1997 contributed to a legislative armoury that fixed and tightened up the conditions for entry and residence in France for foreigners, and which reinforced the idea of immigration as a social and political problem (Lessana, 1998).

12 In 2007 the trade union Alter, the Union of Air France Pilots (SPAF) and CGT Air France carried out a campaign for a vote by the company’s shareholders to stop deportations and so bring pressure to bear on the board of management. On 21st June 2007 the Bulletin of the Air France air crew union (BSPN), published bi-monthly by Alter, carried the headline: “Escort to the border: this is not Air France’s job!” [Reconduite à la frontière : ce n’est pas le métier d’Air France !] (Hamant, Lecadet, 2019)

13 See « S'opposer aux expulsions ? », Plein droit, 62, 2004, p.35-38.

14 “Guide pratique d’intervention dans les aéroports”. This guide was written in July 2000 and published in the review Vacarme, 2000, 3, p. 14-18.

15 “Lettre au président d’Air France de protestation contre les expulsions” 8 December 2003, http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article278

16 “Se rendre sur les aéroports pour s’opposer aux expulsions, c’est être en même temps contre les centres de rétentions, les zones d’attente, les prisons, c’est être contre toutes les formes d’enfermement, contre le fichage de tous dans le SIS ou ailleurs, contre toutes les formes de contrôle et de répression, contre toutes les formes d’exploitation ; mais c’est aussi être contre tous les tribunaux, c’est refuser leurs règles, leurs lois, qui réglementent le contrôle social et institutionnalisent l’exploitation. C’est lutter pour la liberté de circulation et d’installation.” ‘Interventions contre les expulsions : quelques pistes”, July 2004, http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article644

17 Brochure « A chacun le sien... Recension de vautours qui se span du fric avec la machine à expulser », 23 December 2009 https://www.infokiosques.net/spip.php?article763

18 “Ce qui dégoûte le cœur, que la main s’y attaque. Les rafles et les expulsions ne peuvent fonctionner qu’avec des Bouygues qui construisent prisons et centres de rétention, des BNP qui balancent des sans-papiers venus ouvrir un compte, des Croix-Rouge qui cogèrent les camps de rétention, des hôtels Ibis ou Mercure qui s’engraissent en se transformant en « zone d’attente », des Air France qui déportent ou la RATP qui fait le tri pour la préfecture”, In Une lutte contre la machine à expulser [Paris, 2006-2011], 2017 p. 11.

19 « Brèves du désordre belges » in Cette Semaine n°90, September 2006, p.39.

20 “Brèves du désordre allemandes” in Cette Semaine n°91, December 2006, p.22-23.

21 “La Bnl finance la guerre et les lagers pour immigrés. Troupes hors d’Irak, détruisez les centres de retention” “ La croix-rouge gère le CPT de Piandel lago : solidarité avec les immigrés”. “Brèves du désordre italiennes” in Cette Semaine n°88, March 2006, p.24-28.

22 “Pourquoi nous voulons la destruction des centres de rétention”

23 “Beau comme des centres de rétention qui flambent”

24 “Diffusons la révolte… Détruisons les centres fermés et les prisons”

25 The abolitionist viewpoint was also developed in the 2000s in English-speaking activist circles and is today very much present in the United Kingdom, and the United States where the movement Abolish ICE, popularised under the hashtag #AbolishICE, grew in strength in 2017 with the arrival of the Trump administration.

26 “Ils disent que c’est un centre de rétention mais c’est une prison”

27 2008, Feu au centre de rétention. Des sans-papiers témoignent, Paris, Libertalia.

28 “C’est ainsi que notre exigence de réciprocité peut prendre sens. Plutôt que de continuer un lien qui n’a d’autre raison d’être que de maintenir la fiction d’un sujet politique qui aurait, au nom de son statut de principale victime, le monopole de la raison et de donc de la lutte, il nous reste bien d’autres pistes à explorer. Pour être plus clairs, on pourrait dire que la solidarité nécessite une reconnaissance réciproque dans les actes et/ou dans les idées. Il est en effet difficile d’être solidaire avec un sans-papier “en lutte” qui revendique sa régularisation et celle de sa famille sans être aucunement intéressé par une perspective de destruction des centres de rétention” in Corps Perdu n° 1, December 2008, p. 10 http://www.acorpsperdu.net

29 “Le mécanisme démocratique de la citoyenneté et des droits, bien qu’élargis, présupposera toujours l’existence d’exclus. Critiquer et essayer d’empêcher les expulsions des immigrés signifie critiquer en acte à la fois le racisme et le nationalisme ; cela signifie chercher un espace commun de révolte contre le déracinement capitaliste qui nous touche tous ; entraver un mécanisme répressif tant important qu’odieux ; cela signifie briser le silence et l’indifférence des civilisés qui restent là à regarder ; cela signifie, enfin, discuter le concept même de loi, au nom du principe “nous sommes tous clandestins”. Bref, il s’agit d’une attaque à un des piliers de la société étatique et de classe : la compétition entre les pauvres, le remplacement, aujourd’hui de plus en plus menaçant, de la guerre sociale par la guerre ethnique ou religieuse. […]” in “Aux errants, Agli Erranti”, text translated from Italian and published in Cette Semaine n°85, August/September 2002, p. 5-7.

https://infokiosques.net/lire.php?id_article=757

30 “Chevènement veut “punir” les opposants aux expulsions. Il fustige les “fauteurs de troubles” à “l’incivisme fondamental”. by Abdi Niram and Virot Pascal, Libération, 1st April 1998.

31 See “Faisons en sorte que cet euro leur coûte très cher !”, 2003. http://pajol.eu.org/spip.php?article276

32 “Brèves du désordre grecques” in Cette Semaine, n°88, March 2006, p. 36-38.

Return to the top of the article...

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-05-lecadet-walters-struggles-against-the-deportation-machine-on-the-anarchist-track.pdf